Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

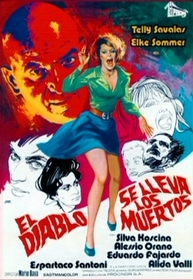

Lisa and the Devil (1973)

The story of Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil is the stuff from which cinema legends are made: brilliant auteur is given carte blanche to make his masterpiece, but the end result can’t find a distributor. To recoup costs, the film’s producer pressures the director to add scenes of demonic possession to cash-in on a popular American film (in this case, The Exorcist). The result of this tampering is released under a different name and, despite being an inferior work, becomes the de facto version for many years. Eventually, the original film resurfaces, much to the joy of the director’s critical proponents.

With a riches-to-rags-to-riches story like that, it’s easy for a film like Lisa and the Devil to become a symbol rather than an artistic work. Since general critical consensus states that House of Exorcism, the aforementioned re-edited "commercial" version, is an unfortunate mess, there’s an urge to deify Lisa, to merely appreciate it for its struggle against obscurity and its rise to usurp the usurper. A blind elevation of Bava’s film, however, does short shrift to Bava himself. Lisa and the Devil is perhaps his “purest” film, unrestricted by conventional narrative and unbound from linear chronology. A bizarre, sepulchral work that plays like the twisted, drug-addicted older cousin of Kill, Baby… Kill!, Lisa and the Devil is at once a horror movie and an art film… with all the positives and negatives such a designation might suggest.

Lisa Reiner (Elke Sommer), a tourist in Spain, sees a medieval fresco depicting the Devil carrying away the dead. Soon after, she is drawn to a little shop where she sees a bald-headed man (Telly Savalas) who looks exactly like the Devil from the fresco. Hurrying away, she becomes lost in a labyrinth of endless alleyways and is accosted by a man who calls her “Elena.” Frightened, Lisa knocks him down the stairs and runs away. Later, she encounters a group of stranded travelers, and together they take refuge in a dark, dusty mansion where a blind Countess (Alida Valli) lives with her morbid son Maximillian (Alessio Orano), and her butler, Leandro, who just happens to be the bald man from earlier. From here, describing Lisa and the Devil becomes an exercise in futility; suffice to say that it is a nightmare mélange of sex, violence, past lives, and plastic mannequins.

Bava’s narrative twists and turns and folds back on itself before it’s even begun. To call it non-linear suggests that scenes take place out of order, as if they had been cut from their proper place in the timeline and dropped somewhere else. Instead, the chronology in Lisa and the Devil seems to have imploded, becoming a bizarre neverwhen where everything that has happened or will happen is happening now. For instance, there is overwhelming evidence that suggests that Lisa is the reincarnation of a dead woman named Elena. However, we know that Elena was a young woman when she died and Elena’s mother does not appear to be any older than seventy. Going by a normal sequence of events, Elena would likely have been quite alive at the time of Lisa’s birth. How can a person reincarnate when they haven’t died yet?

Bava provides an answer late in the film that significantly backdates certain events (and the people in them) by a full century, but this new discovery only leads to more questions. When does Lisa and the Devil really take place? If certain characters have been dead a hundred years, are we seeing their ghosts? If so, why does one of these ghosts wear disco-era lapels as wide as his arm? How do ghosts obtain modern conveniences like tape recorders and electrical tape? Find one satisfactory answer and watch another world of conundrums open up.

Solutions don’t come easily in a film as dense as Lisa and the Devil, a fact that will frustrate even the most observant of viewers. It takes supreme patience to make it through Lisa when trying to watch it as a narrative. For every clue that supports one interpretation of events, a contradiction pops up like a troublesome imp, waggling its naked bottom in defiance. My own personal favorite interpretation, which I will relate later on, is not immune. Truly, the only way to make Lisa and the Devil fit for a completely comprehensive interpretation is to break the film by removing the contrary bits from your memory. As if to acknowledge this, Bava includes a humorous scene where Leandro is attempting to fit a tall body into a short coffin. When the legs won’t go in, he simply snaps the ankles at 90-degree angles, muttering a brief apology to his unhearing victim.

The easiest way to watch Lisa and the Devil is to ignore plot, ignore interpretation, and ignore chronology. About five years ago, director Dante Tomaselli told me in an email regarding his film Horror, “I just want to set up a mood.” To him, Horror was “an experimental film masked as a horror film.” I don’t wish to engage in a critical discussion about whether Horror succeeds under those terms; I bring up Tomaselli’s comments because Mario Bava could have easily made them regarding Lisa and the Devil (although it’s hard to say for sure, because Bava was notoriously interview-shy). Steeping the film in the morbidity that he used as an undercurrent in his previous work, it seems as if Bava used the carte blanche that producer Alfred Leone afforded him to make a “greatest hits” collection of mood and shock, alternating and entwining – a tone poem with murder instead of music.

Of course, “greatest hits” is a loaded term, one that is often associated with mercenary marketing gurus trying to make a new buck off of an old product, but I use it here with the greatest affection. After fifteen years as a film director (and twenty before that in various cinematic capacities), Bava had certainly built up a body of work large enough for revisitation. However, what we get in Lisa and the Devil is not a mere repetition of past glories, but an expansion of them. Bava pushes the macabre atmosphere, the artfully choreographed shocks, and the perversely voyeuristic sexuality of his past films to their absolute limit in Lisa and the Devil. A room is filled with rotting slices of cake, tributes to a long-ago time of happiness (not unlike Ms. Havisham’s wedding day). The pooling blood from a murdered man falls directly onto the camera, turning the lens into a canvas of red. While a man impotently rapes a woman, the desiccated skeleton of the man’s past love lies inches away and actively mocks his efforts, despite lacking a proper larynx. With that kind of insanity going on, it only makes sense that Bava had to toss out conventional, linear storytelling – who has the time?

The film that Bava seems to be recalling the most throughout Lisa and the Devil is Kill, Baby… Kill!1 The Countess’s decrepit mansion may as well be Villa Graps – indeed, the Countess herself bears a striking resemblance to the Baroness Graps from the earlier film. Both have lost blonde-haired daughters and both have allowed everything around them to die and wither since the day their girl was taken from them. Bava uses the concept of a revenant spirit tormenting the living in both films, but to different effects (in fact, one of the mysteries for the viewer of Lisa and the Devil is figuring out who among the characters is the spirit and who is the object of torment). One of the best shocks from Kill, Baby… Kill! is repeated almost exactly in Lisa, with a ghostly figure at a window, hand pressed against the grimy glass, staring in at a frightened girl. The two films share filming locations as well – the same streets of Faleria, Italy that acted as the dark, shadowy alleyways of nocturnal Karmingen in Kill, Baby… Kill! are used for some of the daytime exteriors in the early parts of Lisa2.

Perhaps the most striking similarity between Lisa and the Devil and Kill, Baby… Kill! is the unnerving feeling of reality being upturned by a malevolently amused force. This feeling does not feature consistently throughout the earlier film, but appears in two key sequences – one where the hero, Dr. Eswai, chases after damsel-in-distress Monica through an endless series of the same room repeating into infinity, and another where Monica runs from a ghost down a spiral staircase that literally never ends. Both scenes resemble nightmares, but more intriguingly, the heady rush of adrenaline pumping through them seems to indicate that someone (be it the ghost girl, Baroness Graps, or Bava himself) is having more fun than should be allowed. However, these gaps in reality eventually close, and normality returns.

There are no such comforts in Lisa and the Devil, which starts playing fast and loose with reality the moment Lisa meets Leandro. Before this meeting, Lisa was able to get to the shop easily from the main square. Suddenly, she is unable to find her way back, becoming lost in an increasingly confusing series of streets and alleys. Again she bumps into Leandro, and suddenly a passageway appears that had not been there before. Then she runs into the man who calls her “Elena”, who then appears to die in a tumble down the stairs, only to reappear later unharmed. Such strange occurrences are standard in Lisa, all overseen by the bemused Leandro – the very Devil himself, if his resemblance to the figure in the fresco is any indication. Reality is clay in his hands and he molds it into the shape of chaos.

Of all the excellent performances in the film, Telly Savalas as the mischievous Leandro is the best. Savalas infuses the character with the very heart of the Devil himself. The actor understands that the role of the butler is a conscious choice of the character, one made purely for the amusing irony of the puppetmaster pretending to be the puppet. As such, Savalas maintains utter control of every scene he is in, radiating a smirking confidence that the sordid events of the evening will play exactly as he wants them to. The script puts some fairly heavy dialogue in Leandro’s mouth, but Savalas’s delivery transforms them into clues, leading (or misleading) the audience to the truth of what’s actually happening in the film.

I’ve let little hints about my interpretation of Lisa and the Devil escape here and there, but I felt it best to handle that last, in case you wanted to watch the film yourself and come back to compare notes. Which, actually, you should do. Go on. I’ll wait here.

Finished? Okay, see how this strikes you: Lisa is the reincarnation of Elena, who died a hundred years ago. Somehow, her soul escaped the Devil (or he let it go, for sport). Now the Devil has come to reclaim what is his, but he’s planning on having a little fun first. Taking the form of Leandro, he populates the mansion with golems – mannequins infused with the spirits of the people in Elena’s life. Now these reanimated spirits relive their tormented final days, exacerbated by the presence of Lisa, Elena’s doppelganger. Lisa, in turn, learns in bits and pieces about the crime of her past life – coveting her mother’s husband (and possibly her own brother) – for what soul can go to Hell without knowing its sin? A few more souls (the stranded travelers) are added to spice up the evening for the Devil’s pleasure. All of the “lives” moving through this little play end in violence, just as they had a hundred years ago. When Lisa wakes up in the abandoned, wrecked mansion, it is because the play has ended and the Devil has decided to let Lisa believe that she has escaped him, right before he reclaims her soul on the plane ride to hell that ends the movie.

If Lisa and the Devil isn’t exactly Bava’s crowning achievement, it is only because its ambitions are so grand that I doubt any film could meet them completely. However, in a directorial career like Bava’s, one does not need to be the best to be excellent, and Lisa and the Devil is certainly excellent. Although the film can be a frustrating experience, the jewels of cinematic beauty that I have gleaned from multiple viewings have made the occasional aggravation completely worthwhile. It’s easy to recommend films like Kill, Baby… Kill! because they set out with a simple goal – to frighten and unnerve – and succeed on those simple terms. A difficult film like Lisa and the Devil is not one I can recommend unreservedly, but I wish I could. It’s a film that demands attention, if you’re willing to give it.

- The Kill, Baby... Kill! connections aren't entirely coincidental. The screenwriting team behind that film, Romano Migliorni and Roberto Natale, were also responsible for early versions of Lisa’s script.

- Lucas, Tim. "Believe in What You Think You See." Tim Lucas Video WatchBlog. 16 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007. <http://videowatchdog.blogspot.com/2007/09/believe-in-what-you-think-you-see.html>

A very interesting and

A very interesting and well-written review/analysis of an intriguingly confusing movie. It was a delight to read.

I'm a bit puzzled about one

I'm a bit puzzled about one thing, though. Where in the movie do we learn that Helena/Lisa is the daughter of the Countess? I don't seem to remember this being mentioned or hinted at at all...