Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

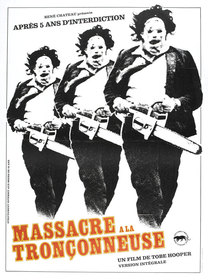

Oil and a Dangerous South: Alternate Geopolitical Readings of "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre"

I know, I know. Provocative interpretations of Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (TCSM) abound. I was reminded of that once again after reading Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film while writing an essay (that had nothing to do with TCSM) for another publication. And of course, our articles and reviews this month served notice once again: TCSM may be the most provocative horror film in American history.

Some film scholars argue TCSM is a hangover from the Vietnam War that reflects our cultural consciousness by revealing how we blindly, numbly have come to accept extreme violence. As Bruce Kawin argues, we watch films such as TCSM to experience "uncontrolled aggression and victimization"1, and as J.P. Telotte notes, TCSM reminds us that life has no intrinsic value or meaning, a reality symbolized by the horrific furniture in Leatherface's home, composed of human body parts.2

Others believe the film reflects radical transformations of the nuclear family. Robin Wood argues that Leatherface's cannibalism reflects the extremes society will tolerate to maintain the nuclear family3; Wood also suggests that the absence of the mother in Leatherface's family causes profoundly dehumanizing results.4

Other interpretations suggest the following: that the film ushers into the American pscyhe a graphic visual depiction of the death of the 1960s and the peace and love it celebrated5; that the film's pro-capitalism view is most poignantly articulated by this horrific mantra: "people have the right to live off other people"6; and that the film's apocalyptic overtones shatter any hope for a collective American mythos.7

That's all fine and dandy, but two critical, alternative interpretations have often been overlooked in the catalogue of TCSM criticism: the film has an underlying ecological message that cannot be ignored given its historical, geopolitical context; and the film continued the trend in American New Wave films of exposing not only a new subculture of disenfranchised rednecks, but gun-carrying, or in this case chainsaw waving, rednecks who represent a serious danger to cosmopolitan youth.

TCSM was shot during the summer of 1973 and released in October 1974. Production occurred during a period known popularly as the "1973 oil crisis," when Middle Eastern countries (mainly OPEC's Arab nations) issued an oil embargo against the United States and NATO nations. America's alliance with Israel and its re-arming of Israel's military during 1973's Yom Kippur War instigated the embargo, which rapidly caused American oil prices to rise, causing nation-wide gasoline-rationing efforts. Fuel became scarce, forcing some smaller, independently owned gasoline stations to close.

I am not suggesting that Hooper deliberately made a film with overt geopolitical, ecological messages. No, no, no. A quick review of the chronology here suggests that the film was conceived, written, shot, and edited before this oil crisis happened. However, what I am suggesting builds upon two important premises. The first is that initial audiences watched the film during a time in American history when the average citizen was keenly aware of these geopolitical dramas and intensely aware of how these dramas were complicating and traumatizing their daily, personal affairs, namely behaviors related to fuel consumption.

Secondly, and more broadly, interpreting a text based solely on an author's intentions, as the "intentional fallacy" - a popular concept in literary criticism - explains, is problematic. "Texts" - poem, novel, documentary, horror film, painting, etc. - contribute to public meaning and possess an organic structure based on their internal details. Directors, authors, and their critics don't own books' or films' aesthetic qualities; the public does. Furthermore, external evidence - including the political and cultural context in which a text surfaces - is as important, and in some cases more important, than an artist's aesthetic intentions. No interpretation of art should ever be limited to the author's intentions. Hooper has downplayed the film's thematic relationships to current events such as the Vietnam War and this oil crisis. However, by denying he didn't intend them, Hooper indirectly confirms their existence. As the intentional fallacy suggests, Hooper's intentions, or in this case his lack of intentionality, are not as important as our critical interpretations. He cannot control how others interpret TCSM.

The first third of the film includes a scene hauntingly reminiscent of what many film viewers were experiencing in 1973 and 1974. Driving to gas stations that had no or limited fuel was a real dilemma many people faced, and this problem caused many Americans anxiety because they had to alter their travel plans, a shift that prompted personal, economic, and social consequences. That fact cannot be ignored, and since the design of a film's narrative arc is as crucial as character, setting, or dialogue, without that early gas station scene, TCSM's narrative is greatly compromised.

The micro-oil crisis in TCSM symbolizes the global oil crisis that unfolded in 1973-1974, and the chaos and horror that follows - including humans cannibalizing random strangers - represents an arbitrary, shortsighted, and malicious hyper-consumption of natural resources that is similar to many Americans' fuel consumption practices prior to this oil crisis. If the 1973 oil crisis produced any enduring result, it was that America could no longer depend on foreign oil, and more broadly, that humans should NOT live off other humans if doing so jeopardizes or degrades either party's quality of life. The realism of this opening scene resonated loudly with audiences and set the stage for the horror inherent in Hooper's other demonstrations of "cinema vérité".

References to the oil crisis abound in the film's early scenes. As the van pulls over for a pit stop to allow the wheelchair-bound Franklin an opportunity to urinate in the weeds, a news report is broadcast from its radio, reporting a series of grisly events. One report, perhaps the most audible, states that unrest in "oil-rich regions...today erupted into violence," an eerie foreshadowing of how the oil crisis globally and, in the context of this film, locally, is producing chaos. When the group stops at the gas station, the camera focuses excessively on the Gulf sign. Of all the gas stations Hooper could have chosen for this scene, he ironically chose the one that represents a region, the Persian Gulf, that's at the epicenter of this geopolitical conflict. And when the gas station attendant reports that he has no gas and that "the cost of electricity is enough to drive a man out of business," (implying that a shortage of or cost fluctuations in another natural commodity such as oil will surely endanger him) we realize how dire this fuel crisis has become.

Moreover, the reason the young couple - Leatherface's first victims - meander through the brush to the cannibals' home is because they are seeking fuel for their van. Again, the horror in TCSM is a direct byproduct of a fuel shortage. And the irony that the film is shot in Texas, one of America's most oil-rich states - and not in Wisconsin where the Ed Gein murders happened - only heightens the dramatic backdrop of this narrative.

One industry the oil crisis traumatized was the trucking industry, and two scenes reveal the role this service industry played in this geopolitical conflict. As Franklin positions himself to urinate, a truck speeds by, disorienting him and causing him to fall down a steep hill. This fall is obviously symbolic, and because the most vulnerable person falls, we realize how powerful and pervasive a problem the oil crisis has become. This event also reminds us that not only does the lack of fuel cause trauma, but the industries that fuel supports cause additional anxieties (especially if deprived of fuel - one can't help but think of the massive truckers' strikes that occurred during the oil crisis). Trucks are often dangerously whizzing by in the film, endangering drivers and roadside walkers. The truck driver who appears during the film's dramatic conclusion, although capable of killing Leatherface's cousin, is incapable of stopping the ultimate source of madness, Leatherface himself. Since Leatherface's weapon, too, is fueled by gasoline, this final scene symbolizes how reliant service industries such as the trucking industry have become on foreign oil. One can't help but wonder if Leatherface gets his gas for his chainsaw from a gas station with ties to the Persian Gulf.

A second alternative viewing of TCSM focuses on Leatherface's family and the historical context in which TCSM emerged, mainly its place in the tsunami of American New Wave films released during the late 1960s through mid-1970s. That unique genre of American films possessed many notable qualities including a tide of provocative themes - footage of drugs, hippies, sex, homosexuality, pornography, and extreme violence, to name just a few - that stunned audiences. Another provocative motif was the depiction of violent rednecks or hillbillies.

In this context, comparing TCSM to two other American New Wave landmarks - Easy Rider (1969) and Deliverance (1972) - might enhance this reading. In each film, redneck hillbillies symbolize a new American South that was rising to power and, in the context of American geopolitics, resurrecting a new political constituency. In historical terms, during the 1970s, the American South's political establishment was rapidly transforming from a bunker of liberalism to a brigade of conservativism. In Easy Rider, a group of Louisiana hillbillies attack the famous trio of liberal protagonists, and later, a group of Florida hillbillies kill one of them. In Deliverance, a family of deep woods hillbillies from Georgia threatens the lives of suburban, cosmopolitan men looking for a good time canoeing. And of course, we know what happens in TCSM.

The similarities here are important. Each film's posse of rednecks is all male, and each resorts to a brand of violence that becomes progressively more disturbing. In Easy Rider, the violence is quick, impersonal, isolated, and deliberate. In Deliverance, the violence is isolated, but prolonged, personal, random, and sexualized. In TCSM, the violence assumes an entirely new face: while it's also prolonged, deeply personal, excessively random, and implicitly sexualized, what we ultimately witness are grisly murders that exist along a continuum of many murders. Leatherface's family is in the business of cannibalism; it's what supports them. While the other films depicted men-vs-men violence, TCSM reveals a grotesquely sadistic "gang-bang" of three men-vs-one woman. Although Sally is never raped, many viewers upon their first viewing probably felt she might be raped. And she is objectified, tortured, and dehumanized by three men. TCSM represents a radical and extreme departure in how New Wave films depicted violence.

However, the contrast in how each "family" of hillbillies is depicted is striking. In Easy Rider, the hillbillies are not a family, but instead, a ragtag group of like-minded rednecks who reject The Other when it enters their community, especially since that Other has ties to liberalism. In Deliverance, the same general pattern occurs, but we do sense these hillbillies are related even though we never fully understand how they're related. But in TCSM we're exposed to a family with clear relationships that, although utterly dysfunctional, is functioning on some primitive, absurd level. They eat meals together, run a business together, and respect their elders. Equally disturbing, we learn intimate details about them, including the décor of their home, their evil lifestyle, their business operations, and how they interact. On a certain level, they are similar to many American families, but what helps distinguish them is not so much their evilness, but their Otherness as rednecks from a rural region of Texas.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre's powerful allure emanates from its rich symbolism: new interpretations emerge annually about the film's aesthetic meaning and impact on the film industry. For classic films such as TCSM, we should celebrate that wild diversity, not limit its interpretative possibilities. Hopefully, these two readings will continue the robust discussions and debates about this seminal American horror film.

- Kawin, Bruce. "The Mummy's Pool." Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film. Eds. Barry Keith Grant and Christopher Sharrett. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press Inc., 2004. Page 14. (back)

- Telotte, J.P. "Faith and Idolatry in the Horror Film." Planks of Reason. Page 24. (back)

- Wood, Robin. "An Introduction to the American Horror Film." Planks of Reason. Page 124. (back)

- Wood. Page 130. (back)

- Wood. Page 129. (back)

- Wood. Page 132. (back)

- Sharrett, Christopher. "The Idea of Apocalypse in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre." Planks of Reason. Pages 300-320. (back)