Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

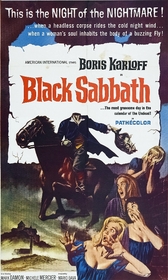

Black Sabbath (1963)

Anthologies, movies that are composed of a series of short films, are always hard to characterize. If the film is considered as a whole, does a particularly bad sequence besmirch the merit of the others? Or does a well-shot segment bolster one that's floundering? Considering each segment individually also presents certain challenges, particularly if each segment was directed by the same person, or starred the same actors. How do you explain trends in performances or cinematography, or persistent themes and plot lines? Mario Bava's Black Sabbath is no exception to this conundrum. While each segment is a work until itself, each showcasing a particular subset of Bava's talents, together they work synergistically, showing a linear progression of time, theme and cinematography.

Black Sabbath is composed of three segments, with a wraparound hosted by Boris Karloff. In the first segment, “The Telephone,” Rosy (Michèle Mercier) has just returned home and is receiving disturbing and threatening phone calls from someone who seems to be able to see her ever move. The second segment, “The Wurdalak,” follows a young noble, Vladimire, who discovers a headless corpse stabbed through the heart with a knife. When he seeks shelter at a local farm, he discovers that the knife belongs to the patriarch of the family who has gone out hunting a ruthless murderer, rumored to be a vampiric being called a wurdalak. When the patriarch returns after midnight, something is not right. Is he, in fact, just tired and hungry, or has he been turned into the dreaded creature, here to prey upon the blood of his loved ones? The series concludes with “Drop of Water.” Helen (Jacqueline Pierreux), a nurse, is called in the late hours of the evening to tend to the body of a woman who has died while in a spiritual trance. When she arrives, a glittering ring catches her eye and she steals it before the woman's caretaker notices. Unfortunately for Helen, the dead are rarely forgiving.

From a horror standpoint, “The Telephone” is probably the least impressive of the three sequences. There is no supernatural threat, and the real threat is actually just randomly realized at the very end of the sequence, having no bearing on the actual events that have been taking place up until now. However, despite this serious flaw in spooky storytelling, “The Telephone” is still a masterful example of plot by insinuation. There are two main character relationships detailed in this segment, the one between Rosy and Mary, and the one between Rosy and Frank, the man Rosy believes to be behind the phone calls. However, as the story progresses and we discover that it is Mary behind the phone calls, using the information she has about Frank and her knowledge of Rosy's habits to create the illusion of a threatening Peeping Tom. None of this plot actually, explicitly, states any kind of backstory, but many things can be inferred from the plot and dialog. It becomes clear that Rosy once had an illicit affair with Frank, and that her testimony put him in prison. Further, as the story progresses, we learn that Mary is not only an estranged friend, but also a lesbian, and possible ex-lover, whose sexual desire for Rosy led to their estrangement. It's difficult to say how these relationships are revealed in the segment, because they are done so subtly that they simply become part of the characters. We see hints in character actions, such as how well Mary knows Rosy's habits at home and could predict her reactions, or in Rosy's stricken face when she sees that Frank had been released from prison. Using very little exposition, Bava manages to give us a complicated backstory so expertly that we are barely aware we are receiving it.

In addition to the detailed, but subtle backstory, the cinematography is also quite masterful. For the first half of “The Telephone”, the camera is limited and subjective, focusing on Rosy while actively sweeping around the room. In one particular scene, when Rosy answers the phone in nothing but her robe, the camera follows the length of her body, lingering on her exposed thigh, as the mysterious caller describes the effect her body has on him. Further, the camera's view is focused primarily on the table containing the phone, and is unable to accurately follow Rosy movements to the farther reaches of the apartment. While the obvious effect is to associate the camera with the caller's-eye-view, the limited scope of the camera also makes the scenes seem more claustrophobic; the apartment appears to be smaller than it really is. This claustrophobia increases the sense of immediate threat, causing the audience to feel like the caller's gaze is closing in. The lighting is also used to a similar effect early in the segment. When Rosy fears that the mysterious caller is able to see into her apartment, she dims the lights, obscuring the room in shadows. Contrasted to the originally clean-cut, well-lit atmosphere, this new, darker, noir-ish look is more dangerous, more sinister. While the intent is to obscure the view of the threat, the effect is to obscure the view of Rosy and the audience, making it seem as though shadows are encroaching, danger ensconced in every darkened corner.

The quality of Bava’s direction only improves with the second segment in the trio, “The Wurdalak”, which is a beautiful showcase of atmosphere and some surprisingly avant garde themes. The settings for “The Wurdalak” can be broken down into two groups – outdoor scenes and indoor scenes. Unlike the other two features, some of the footage for “The Wurdalak” was shot outside on location in Canale Monterano (see Tim Lucas’s “Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark”, page 502), adding an openess to the piece that the other features lack. What is impressive, however, is that not all of the outside shots were done outside – several of them were filmed on set in Cinecittà (Lucas, page 502). While the “day for night” shots generally give away which scenes were done on location, it is sometimes easy to forget which is which since, in either scenario, the scenes are heavily fogged and awash in a eerie blue light that creates a faint glow in the faces of the characters. The effect is downright creepy, and, once the threat of “The Wurdalak” is revealed, the wide sense of space, coupled with the limited visibility of the light and fog effects, makes it seem as though danger could be lurking just three steps ahead. If you're looking for the classic, creepy woodland, this is it.

The outdoor scenes are strongly contrasted by the indoor shots, particularly those that take place at the farmstead at which Vladimire originally takes refuge. The family home is well-lit and rustic, which gives it a comforting air – at first. However, as the family becomes restless, waiting for Gorca to come back from th, wondering if he will return a man or a monster, the brightness almost seems mocking, drawing attention not to the warmth within, but to the cold danger without. When Gorca finally does return, and we begin to suspect that he has fallen to the wurdalak, the light becomes more sinister, as if offering another layer to his ruse. How can evil infiltrate such a bright, warm place? Like a small child clinging to a night-light in the wee hours of the morning, we too cling to light and hope, denying the obvious evidence that evil is among us.

The prevalence of evil in this segment is another of its strong suits. In this respect, “The Wurdalak” was a true innovation in its time, doing what no other film had dared to do before. When the film concludes our hero, Vladimire, who tried to escape with the girl and failed, returns to the homestead to find her. However, rather than finding her alive and well and riding off safely into the night, he finds her sitting on her bed, staring up at him with an unearthly gaze. When she beseeches him for a kiss, he complies, submitting not only to her lips, but also to her cursed bite. At the conclusion of “The Wurdalak”, there are no survivors. The entire family, including Vladimire, their newest member, has either been killed or turned. And yet, despite this atrocity, there is no judgment, no understanding that evil will eventually be thwarted and no greater theme or meaning in the failure of good to emerge triumphant. The wurdalaks, like most evils in the world, simply exist, and the lack of a happy, or at least moralistic, ending was something unheard of in 1963, predating such classics as Rosemary's Baby and Night of the Living Dead, which are noted for the same themes.

It is also important to note that the evil in “The Wurdalak” is not amusing, or stupid, or otherwise tempered. It is perverse and ruthless. The wurdalaks are known, in particular, for craving the blood of the ones they love the most, twisting what is often considered the high point of goodness into a mark of death. Further, one of the first victims to be turned into an undead creature is a small child. Evil has tainted and violated the most innocent of the story's characters, something that is considered risky in today's storytelling, let alone the stories of the 1960s.

The final segment in Black Sabbath is “Drop of Water”. This is probably the most effective, horror-wise, of the three segments. While I watched “The Telephone” and “The Wurdalak” in morbid fascination, I watch “Drop of Water” cowering in the corner of the couch. The reason for this is, simply, sound. Bava uses sound in a way that is nothing short of genius. We first realize that sound, more than any other element, will be key in this featurette when Helen first appears on screen. She is preparing dinner and, for entertainment, puts a record on the phonograph. As the lovely classical music fills the air, Helen receives a call about a job and, after some consideration, says she will take the work. She walks outside, leaving the camera lingering on her uneaten dinner, the phonograph playing in her absence, slowly winding down, distorting the once beautiful music into a grotesque mockery of itself.

Later in the sequence, when Helen steals the ring from the dead body, she is shocked to see the corpse staring at her accusingly, and accidentally knocks over a glass of water. The room fills with the loud, methodical dripping of water, slow and unrelenting. Each drip is punctuated by silence until being suddenly broken by yet another drip. During the haunting scene, this same effect is repeated as Helen's house comes alive with the sound of dripping water, the only break in the otherwise pervasive silence. The staccato, discordant nature of the water assaults the viewer’s ears, evoking a visceral reaction. It is unpredictable, leaving the ear waiting for the inevitable “plop” of water that will, again, break the quiet. The suspense of waiting for the dripping water bleeds into other aspects of the segment, including the actual appearance of the apparition. Like a break in the silence, one moment there is nothing, and the next, the old woman's spirit has returned for revenge.

This disharmony of the senses, brought on by nothing more complicated than dripping water, is complemented by a similar use of light. When Helen returns home, the lights outside are flickering through the open window, flipping on and off. It would seem natural to assume it is a storm, but the unearthly wavering is not accompanied by the usual rain and thunder that comes with lighting flashes, Whatever the cause, however, the effect is the same. The house is bathed in light, before descending into shadow and darkness. With each flash of light, we are given a momentary glimpse of the room, soaking in as much detail as our brains can hold, before everything goes dark again. Because the flashes are momentary, what we see in the room isn't actually processed until it is again dark, forcing us to analyze the shapes and images of the lighted room in shadow, with no way to verify if our memories and impressions are correct. Further, the periods of shadow hide any changes that may be taking place in the dark. Swathed in shadow, things can move without being noticed, sneak up behind you unawares, and you won't know until the next burst of light. In fact, this is exactly what happens when the apparition appears. Helen, having moved around the house, shutting off the infuriating dripping faucets, is now making her way, in shadow, back to her room. As she begins to walk through the door, the light flashes back on and the face of the dead woman is staring back at her, and at us. It almost lends credence to any irrational fear of darkness.

I've offered my thoughts on each segment of Black Sabbath in the order they appeared in the original theatrical release of the Italian edit. There is a separate American edit, which is not discussed here (nor will it be). However, when the film was originally conceived, the segments were ordered differently – “The Telephone,” “Drop of Water,” “The Wurdalak” – but were changed before final release for undetermined reasons. When the segments are reordered as mentioned, it offers a new, significant chronology to the work as a whole. For the next segment of the review, I'll be considering how the segments work in synergy, in the order they were originally written and filmed (if not released).

What is most notable about Black Sabbath is its sense of backwards chronology. The first segment, “The Telephone”, is set in the early 1960s, with modern furnishing with modern characters. The next segment, “Drop of Water”, moves backwards, stepping into the previous century, the settings darker and more gothic. Finally, “The Wurdalak”, takes us the farthest back in time, into the 1700s, the setting and mood darkening yet again to reflect the passage of time. While the chronology is not important unto itself, it sets the stage for several feature-wide themes in Black Sabbath, most notably the nature of evil.

In “The Telephone”, there isn't a real threat for the most of the segment, and, when the threat finally does appear, it is completely human in nature. Frank isn't supernatural; he's just angry. The telephone calls are threatening, not spooky. When all is said and done, everything in “The Telephone” has a rational explanation rooted in human relationships. “Drop of Water”, however, is not so clear-cut. As we move back into the past, the lines of reality become blurrier. Given that Helen strangled herself to death, it is never clear whether she did so because she was compelled by the angry spirit of the dead medium, or if she was driven crazy by her own guilt. The threat, therefore, is both human and supernatural. Finally, in “The Wurdalak”, there is no mistaking the supernatural element. In this segment, the patriarch of the family begins to prey on the household members, most of whom rise from the dead. The threat is monstrous, devoid of humanity, and completes Black Sabbath’s descent from reason to superstition. Coupled with the chronology of the three segments, Black Sabbath also offers a small, obscure opinion on the evolution of the human condition. While man once had nothing to fear but monsters in the dark, we now worry about the threat of our fellow man in our well-lit homes. Where evil was once external, it has become internalized as society has progressed. In Bava's film, the final resting place of evil is us.

Black Sabbath is not your typical anthology. While it certainly follows the basic format, showing three short-form featurettes within the frame of a single movie, Bava's work is moving towards a greater purpose, following a significant progression and chronology. Each feature showcases Bava's particular skill with light and sound and intimated backstory. However, when the segments are taken together, Black Sabbath traces back the denigration of the human condition, and makes some startling conclusions about the actual source of evil.

This review is part of Mario Bava Week, the last of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

Dear Julia, This is

Dear Julia,

This is my first visit to classic-horror.com and I happened upon your review of Black Sabbath. I really enjoyed the review and I am happy to find a site that treats these genre films seriously. I always thought that this, along with his role in Targets were the finest performances from Boris Karloff's later career. I will be coming back soon to read more reviews at this site.

Thanks

Drop of Water is absolutely

Drop of Water is absolutely terrifying! I saw it as a kid and the image of the old woman's face has given me nightmares ever since. In fact, I have recurring nightmares that involve me walking up some stairs and into a room with a woman that looks like this lying on a bed. Damn it has left me scarred!