Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

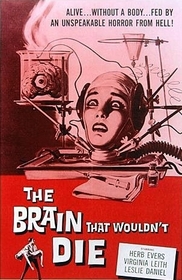

The Brain That Wouldn't Die (1962)

The Brain That Wouldn’t Die is a cult horror classic that, itself, refuses to die. Resuscitated by Elvira’s Box of Horror Classics series and "Mystery Science Theater 3000," The Brain’s no-name cast and low-budget schlock are not as corny as expected. Although splattered with goofy flaws and over-the-top performances and producing plenty of chuckles, the film probes primitive fears that should unnerve the most stoic spectator.

Enter Dr. Bill Cortner, an ambitious, diabolical surgeon eager to revolutionize the world of transplant surgery. Cortner, his father, and nurse Jan (Bill’s fiancée) are engaged in an operation (the family that operates together, stays together?), but Pop Cortner, the lead surgeon, loses the poor soul. Bill revives the patient with unconventional procedures, proving that his zest for exploring science’s fringes has merit. Later, Bill and Jan drive to his laboratory, which is disguised as a vacation home in the woods. In a hurry (his assistant called him to come, quickly!), he swerves off the road, crashes, and Jan suffers a horrible fate. Bill revives her in his laboratory through a surreal procedure, and to reattach her missing part, stalks local erotic dancers, hoping to seduce them and “complete” Jan through a grotesque transplant procedure. However, Jan’s anger (why couldn’t he just let me die!) compels her to carve an alliance with a creature hidden in the closet, and when it escapes, Bill’s medical destiny is sealed.

The Brain relies heavily on the Frankenstein cycle and its mad scientist themes. Bill is the confident doctor determined to defy natural order, play God, and plunge into science’s unexplored depths. He is obsessed with pushing science into its next evolutionary phase with, of course, the help of a deformed assistant. His laboratory is tucked away, like Frankenstein’s castle, along society’s edges, and he yearns to recreate his bride with others’ body parts. “Jan in the Pan’s” resemblance to Elsa Lanchester in The Bride of Frankenstein, with her pale face and dark eyes and eyebrows, is no coincidence.

The Brain’s weird, quirky charm also tantalizes because it taps into primitive male emotions. Bill wants to overcome his father’s conservative medical philosophy, a contemporary spin on the archetypal Icarus and Daedalus myth. The good doctor also wants to “fix” his girlfriend and provide her with a sexier body. Since before the accident Bill stated (without explanation) that he would not marry Jan, his transplant surgery is all the more sinister. Most erotically, though, is the beast “in the closet,” which harbors homoerotic overtones. The mutant represents Cortner’s “mistakes,” which he refuses to make public because of the shame they’ll bring him. Through repressed verbal teases and commands, Jan in the Pan forms a bond with the beast, which moans frequently, and its head is deformed with only one eye. The actor Eddie Carmel, who was born in Palestine and later became a popular circus attraction as “The Jewish Giant,” plays the beast (later in the film, his mask almost comes off). That Cortner is more infatuated with his experiments than his amorous girlfriend makes one wonder what other transplants Bill has planned.

The film also drags a major social issue, euthanasia, onto the debate floor. Jan wants to die, but Bill selfishly won’t let her. Because his rationale for preserving her brain, which resembles a jellied frog waiting for dissection, is woven into a complex web of scientific ambitions, carnal lust, and love for sweet Jan, our reactions to his absurd decisions are muted. The Brain thus is a manifestation of this nightmare: loved ones don’t love you for who you are, but rather, for who they want you to be, and if given the opportunity to change you, they would, regardless if that change produces agony. In essence, their self-gratification is more important than yours.

Exploiting the public’s growing interest in horrific and sexually explicit topics, The Brain is exploitation cinema at its best. It teases by prolonging the beast’s appearance; we know something hideous lurks, but we don’t know what. Nevertheless, the payoff is worth the wait. The disturbing image of Jan’s head on a laboratory pan, talking as if only a minor setback has occurred, exploits our blackest fears of dismemberment, claustrophobia, and torture. At least one interesting scene of graphic gore is offered. Furthermore, since only years earlier nudist camp films were blossoming and sexuality in cinema was generally lunging from the closet itself, the scenes in erotic dance clubs helped fuel the emerging sexploitation genre. Although hilarious, when two dancers wrestle (one wearing a bustier), viewers cannot help but wonder what new social trend this odd narrative reflects.

The music, pace, editing, and at times even the cinematography (particularly during the car accident scene) work well enough to dismiss the film’s many flaws. Dealing with such primitive themes in a camp full of so many guilty-pleasures is perverse, but perversity is attractive, at least to some. Much of the plot makes no sense, and the science behind Bill’s procedures lacks any reasonable grounds, thus disqualifying The Brain from any serious sci-fi consideration. The operation room scene makes "E.R." look technically proficient (which it’s certainly not), and Bill’s lab looks like a boring 6th grade science classroom.

Filmed in Tarrytown, New York in only two weeks and costing approximately $125,000 to produce, The Brain That Wouldn't Die, given its unique place in American popular culture, was worth the investment. That the film has fallen into the public domain and can be downloaded on the Internet is proof that poetic justice exists. I’ve never understood why some people, like myself, are so infatuated with B-horror flicks. I’d like to think there is some karmic pool of energy out there that we’re connected to. Or, maybe, I’m just attracted to the idea that my brain may never die.

A theater in San Antonio, the

A theater in San Antonio, the Overtime Theater, is adapting “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die” into a stage musical! It’ll have 15 original songs complementing the overcooked dialogue and cheesy plot, and will be staged in October 2009. The musical will explore many of the same themes you've mentioned.

Very cool! I, for one, look

Very cool! I, for one, look forward to hearing more about this project. I hope there's at least one song devoted to decapitation puns.

"He went for a little walk! You should have seen his face!"

Just saw the film on MGM's

Just saw the film on MGM's channel. I was struck with its attempt to discuss transplantation seriously. "some day, we will not just be transplanting corneas", Bill says. And there is his mysterious serum which overcomes rejection of transplants.(But also seems to have deleterious effects on Jan's mind, turning her into one angry talking head (Is that where the term comes from?). [How she can talk isn't even approached]. I'll have to check, but the speech about transplantation and antibodies seems to have been state of the art understanding in 1959, when the movie was made.

Of the many strange scenes, though, I cannot for the life of me figure out what the "cat fight" between the two strippers was put in for. Is Bill watching this? Is he hoping that one would kill the other, so he could take the body?