Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

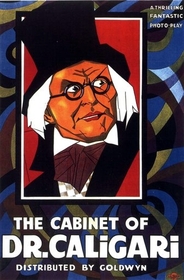

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Everything has to start somewhere. And, in Post-World War I Germany, a cinematic breakthrough was brewing: Carl Mayer, an Austrian scenarist and Hans Janowitz, a Czech poet, conceived the tale of a psychotic madman who could control another human being and drive him to murder. While that may seem rather common place these days, the concept, which influenced later films of the genre (such as Murders in the Rue Morgue, 1932), was positively novel in 1920. With the help of director Robert Wiene, a meddling producer, and a team of brilliant production designers, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is now a landmark in film history, both within and without the horror genre.

At 71 minutes, Caligari’s story is pretty straightforward, almost mundane by today’s standards. The story opens with our hero, Francis (Friedrich Feher) speaking to a stranger in a garden. As the tale begins, the garden scene fades out, and we enter what appears to be a flashback. As events unfold, we discover that a stranger has come to town, a man by the name of Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) and with him Cesare (Conrad Veidt), a somnambulist (for these purposes, a person who is in a death-like trance). Shortly after their arrival, people around the village begin to die, including Francis’s close friend. As Francis, suspecting Caligari, begins to investigate the strange somnambulist, the danger only grows. When Francis's love interest, Jane (Lil Dagover) is threatened, the film rushes towards a predictable climax, which, just in case you can’t guess it, I won’t reveal here.

Overall, the plot seems almost stagnant, as if it has nothing new to offer. It seems obvious from early in the film that Caligari is controlling Cesare in order to commit these murders. It’s hardly a surprise when Cesare attacks Jane, the only pretty woman on the screen available for damsel-in-distress duty, and the shocking twist ending is so predictable you’re almost surprised they actually follow through with it. However, while Caligari may seem mundane, it’s imperative that we remember this was made in 1919. Every cliché has to start somewhere, and this one? It started right here. This is the real McCoy, and it would do any film aficionado good to sit up and pay attention. While there may not be anything surprising in the storyline, as the basis for all similar films to follow, Caligari is invaluably educational. How can you expect to appreciate modern film if you don’t bothered to understand where it comes from?

Lucky for us, there’s no need to be bored to tears while continuing our education. While the plot may be a bit dry, the set is unlike anything seen by many modern viewers. Most of the set (designed and implemented by Hermann Warm, Walter Röhrig, and Walter Reimann) is a two-dimensional backdrop constructed of paint on flat canvas. The image of three-dimensional people walking through this starkly two-dimensional world is disorienting, making the universe within Caligari seem slightly off-kilter. As if that wasn’t enough, the entire “flashback” set is done in German Expressionist style, with unnatural angles, exaggerated line and an overall trend towards asymmetry. In particular, in many scenes, the shadows were actually painted onto the set, such that, in certain scenes, the shadows lie in direct defiance of natural lighting. The effect creates an unnatural world, in which city officials teeter on impossibly high chairs, triangular doors open at odd angles, and buildings teeter in such a way as to defy gravity. And, worst of all, the shadows never fail, never move, giving the impression that the even the town itself has descended into madness.

The actors, too, seem to fit perfectly into this twisted Wonderland. The acting is almost overdone, with wide gestures and almost comically exaggerated faces. And yet, against the exaggerated backdrop, it seems almost natural. Cesare, in particular, almost blends into the harsh lines of the set. Tall and lanky, the somnambulist is dressed all in black, with a wild shock of black hair and dark-rimmed eyes. When he moves, it is slow and deliberate, accentuating his outline and making it’s almost too easy to imagine him as a one of the other painted-on shadows lurking on screen. Cesare, with the help of the set, creates the illusion of a world in which even the shadows can kill you. The exact opposite of Cesare would be none other than his puppetmaster, Dr. Caligari. While Cesare blends into the background, Caligari stands out as a lively, terrifying creature removed from the world. He is animated, moving almost spastically, as if in defiance of the carefully crafted madness of the sets around him. And yet, Caligari is undeniably insane. The effect of Caligari’s character is stunning: the creation of a world in which the lunatic reigns, in which a madman pulls all the strings. Werner Krauss’s sinisterness on screen cannot be denied, and of all the characters, he is the only one not being controlled, either by force or by fear. In an insane world, insanity is power.

At this point in the review, it becomes necessary to discuss the “surpise twist ending”. So, if you’re worried about it being spoiled, I’d recommend taking a walk, or maybe getting a cup of coffee. Because, the secret surprise is that Francis is actually insane. That garden in the opening scene was, in fact, the grounds of a mental institution at which Francis, as well as Jane and Cesare, is a patient. And Dr. Caligari? You got it. He’s the medical director in charge of treating name here. After the big reveal, the movie ends with the medical director/Dr. Caligari explaining the nature of the delusion and exclaiming excitedly that he will now be able to cure Francis.

It should first be noted that this framework, while predictable today, was groundbreaking at the time. It laid the foundation for later films, such as Psycho, in which the “reality” we see is, in fact, nothing more than a madman’s delirium. The whole psychoanalyst explanation segment at the end, also, was a first, and something that would be used by later films across genres. However, while the implementation of this twist, itself, is responsible for great things in cinema, it was a decision that was both detrimental and beneficial to Caligari’s long-term success.

Screenwriters Mayer and Janowitz intended Caligari to be a reflection on the state of post-war Germany, commenting on the authoritarian structure and, in Janowitz’s own words, demonstrating that “reason overcomes unreasonable power.” However, director Wiene and producer Erich Pommer were both uncomfortable with blatantly challenging society’s strictures, and constructed the end-caps sections, which were not part of the original script, to soften the blow.1 Dr. Caligari was no longer a crazed authority power, but, rather, a figment of a madman’s delusions. It diffused the entire original message of the film. However, this change also had two unintentional side-effects on Caligari: it effectively neutered Caligari as horror, while simultaneously making the film more accessible to the audiences of today.

It’s easy to understand how simply explaining away the horrors of Caligari as a hallucination would put a damper on the scary factor. In the original script, we have the tale of a murdering lunatic, who can control the mind and will of another person to carry out his nefarious plots. It’s not a bad basis for a horror film. Hypnotism is poorly understood and most audiences, modern or otherwise, are familiar with the power of charisma on the weak minded. When you really stop to think about it, it’s something that we could almost imagine happening in the real world. If you continue the line of thought, Caligari’s strange world then becomes a little too close and relevant to our own. The shadows at night are just a little too dark, the lines of the trees on our street just a little too tall. Caligari is the stuff of horror, just one step past our own reality, which is just a little too close for comfort. Or, it was the stuff of horror, until it all got explained away by fantasy. Once that ending is revealed, the illusion shatters. The world of the murdering somnambulist could never be our own, it’s all just crazy talk, made up by a disturbed mind. Safety and sanity are irrevocably restored, and it’s downright disappointing.

However, by providing this explanation for the story, and, by association, the bizarre world created by the Expressionist sets, Caligari is made far more accessible to modern audiences than had these end caps been left off. German Expressionism is meant to use its bizarre forms, dramatic lines and strange angles to give physical shape to the artists' emotions. As discussed above, the Expressionist style in Caligari creates a world of madness and disorder, and it does this regardless of the endcaps. However, its effectiveness doesn’t make it any less strange and trying to watch, especially for those not familiar with the movement. The world is disorienting, at times distracting and impossible for the scientific mind to reconcile. And then comes the framework. Suddenly the irrational, visceral Expressionist world is explained in a rational, logical way, making the film more versatile and accessible to most anyone, regardless of the political, scientific and spiritual movements of the era.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, having been ravaged slightly by the passage of time, doesn’t necessarily qualify as an awesome film, but it is great film. It’s a seminal work of the genre, and defined many of the tropes that, today, form the basis of modern horror. And, despite a moderate loss of efficacy, Caligari remains a moving, enriching experience. Not only does provide an engaging visual experience, unlike any other, it offers something few other films can – the background and foundation to better understand and appreciate those films that followed in its footsteps.

This review is part of German Horror Week, the third of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.

1 Leydon, Joe. "Expressing Paranoia: 'Dr. Caligari.'" MovingPictureBlog. Published 22 October 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2008. <http://movingpictureblog.blogspot.com/2006/10/expressing-paranoia-dr-caligari.html>

The best review of the many I

The best review of the many I have read on this film.

Wenceslao

I thought fritz lang

I thought fritz lang suggested the story being softened, with lang even rejecting directing the movie.

One of the best of examples

One of the best of examples of German Expressionism.

While the story is kind of mundane as you said, if you're able to extend your suspension of disbelief, you can go with it. It's a good story for the most part, and it was the groundwork for the horror genre.

Plus, it laid out the visual framing and such for suspense thrillers such as Psycho.

Would've loved to see the 1936 sound remake of the film.

I believe you are correct,

I believe you are correct, Sakara. I think Fritz lang wrote the delusion twist at the end of the film.