Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

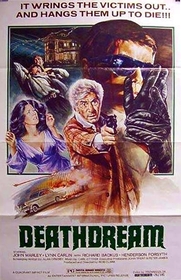

Deathdream (1974)

Known originally as Dead of Night but released in America as Deathdream, Bob Clark’s second foray into zombie cinema is an engaging, well invested 88 minutes of thrills, technical artistry, and provocative social commentary about the Vietnam War.

Clark’s early career essentially started with three horror flicks: the zombie films Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) and Deathdream and the slasher classic Black Christmas. In the late 1970s, he turned to crime dramas with Breaking Point and Murder by Decree. By the early 1980s, his comedies Porky’s, Porky’s II, and the iconic A Christmas Story earned him an office in CinephileLand. Not withstanding that eclectic run, it’s Clark’s early work in horror that put him on the map.

Besides unveiling Clark’s directorial talents, Deathdream also served as training ground for two other horror stalwarts: Tom Savini and Alan Ormsby. Savini’s talents need no further explanation here, but it is worth noting he considers Deathdream an important rung on the ladder of his success. The DVD features a 10-minute short about Savini titled The Early Years that is worth watching. Ormsby wrote Deathdream, and he later wrote Cat People and The Substitute. Also in 1974, Ormsby directed and wrote Deranged, a biopic about serial killer Ed Gein that showcased Savini’s early makeup work.

Deathdream’s plot is straightforward, and that relative simplicity allows the film to shine. Andy Brooks is a Vietnam soldier killed on the battlefield. While dying, he is transfixed by an ambiguous something. Back home, a soldier reports the tragic news to the Brooks family. However, something is amiss, and Andy appears back in America as a traumatized, speechless hitchhiker. Much later that evening, hours after a tranquil Brooks family dinner, Andy returns home. The family is ecstatic, but Andy is tuned out. He stumbles through the motions, but eventually, the family’s happiness turns into curiosity and later fear over Andy’s condition. Something is definitely wrong with him. Mr. Brooks and Andy’s relationship becomes increasingly strained as it becomes clear Andy may have been involved in two local murders. After some creepy scenes and exchanges that further reveal Andy’s monstrous state, his menacing presence is obvious. The film culminates in a date with his old girlfriend that turns ugly.

The cinematography in Deathdream casts a splendid gloom. Two years later in Black Christmas, Clark fully developed his eye for cinematic horror, but in Deathdream those cinematic seeds are planted. The early war footage, although brief, is courageous and haunting, especially since this film is one of those war flicks that indicts War without focusing on battlefield nightmares. The carefully crafted suspense conjured in the doctor office scene is hair-raising, especially with Clark’s use of shadows and night-for-night shooting. Another poignant cinematic motif is the staircase in the Brooks house. Complex and maze-like, it is an expressionistic symbol of the family’s psychological angst.

I’m always amazed how zombie films can skip explaining how or why the zombies emerged. They just did and that often seems enough. This is true in Deathdream as well; Andy dies in Vietnam, then suddenly, he turns into a zombie. Why? Who cares? The film is a vehicle for exploring much more complicated themes and adds intriguing twists to the zombie mythos.

Andy is as much a vampire than anything else because he feeds more on blood than human flesh. He wants transfusions, not body parts. He also can exist awkwardly in a trance-like state among the living. He hides his monstrous side with clothing and secretive behavior like The Invisible Man or Mr. Hyde. Although he obviously can only hide for so long, his attempts to blend in are fascinating. Is he hiding because he wants to conform as Andy the civilian? Or does he blend in to lure his prey and ultimately nourish Andy the zombie? Richard Backus’s devilishly stoic performance as Andy forces us to choose. He eventually dates his old girlfriend, but at the film’s conclusion, he seems no longer satisfied with his zombie status. Strangely, he seems more satisfied with The Other Side. This may be a commentary on the zombie film itself. His characteristics and actions produce a tragic, sympathetic, and complex zombie.

The film never fills some basic plot holes, which inevitably challenges its logic and rationality. For example, how did Andy return home from Vietnam? Why exactly is he a zombie? Why doesn’t the family question the military’s initial claim that Andy died? Why doesn’t anyone realize earlier he is a zombie? These are legitimate questions. However, such plot holes make sense if one reads the film as a deranged, metaphorical fantasy dreamed by families grieving over their deceased children who died in combat. The Brooks family is initially eager to overlook Andy’s traumatized state and the apparent contradiction of his return because they are overjoyed he is alive. That seems normal. The film’s title obviously refers to a dream, and nothing is rational in a dream. The family also is reluctant to believe Andy is guilty of anything. They just want their boy back, and they are willing to believe anything.

The film’s greatest strength is clearly its commentary on the social implications of the Vietnam War. Andy’s struggles on the home front are a metaphor for the difficulties many combat veterans have, regardless of their war, when returning to civilian life. Andy’s friends back home are incapable of understanding his traumatic experiences. Although this misunderstanding does not cause his evil actions, he nevertheless is perceived as attacking and killing those who don’t “understand” him. Andy’s monstrous psychological condition is exaggerated to demonstrate how severe the horrors of war are. The effects of the war literally tear this family apart and have literally turned this soldier into a monster. In 1974 America, these wounds were all too fresh.

Political and social overtones aside, Deathdream is a neat chapter in the Book of Zombies. Replete with solid makeup work, piercing social commentary, and excellent direction, it is a dream worth realizing.

is there anyone in the world

is there anyone in the world who knows the singer and the song when Andy's father is in the bar in the film

Deathdream, Dead of Night ?

please let me know

margreet_1999@yahoo.com