Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

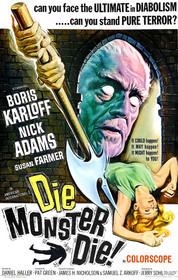

Die, Monster, Die! (1965)

Although HP Lovecraft is one of the most revered, recognizable names in horror – what other author has spawned both a table-top roleplaying game and a line of monstrous plushies – cinematic adaptations of his work are few and far between. Don G. Smith’s “H.P. Lovecraft in Popular Culture” lists a scant fourteen films directly taken from his stories and novellas (although more certainly exist). It’s not difficult to see why. Despite an amazing talent for atmosphere, Lovecraft’s stories approached horror from a subjective emotional experience. Locations and ghastly beasts alike were described by the effect they had on a character, and even that was often beyond the scope of mere words. While such a technique makes for an imaginative read, it also presents a peculiar challenge to the filmmaker looking to create a concrete visual out of it. Some choose to take only the basic concepts and attempt to make them fit with whatever was selling tickets at the time. Such is the case with director Daniel Haller and writer Jerry Sohl when they made Die, Monster, Die! – a film ostensibly based on Lovecraft’s "The Colour Out of Space" that more closely resembles Roger Corman’s recently completed Poe cycle.

Strange things are afoot at the Witley place. The servants are disappearing. The mother, Letitia (Freda Jackson), who has been sick for weeks, is hiding in her bed, her features hidden by a curtain. The father, Nahum (Boris Karloff), has forbidden visitors. At night, the locked greenhouse shines with an unearthly glow. American Steven Reinhardt (Nick Adams) has come at Letitia’s request to spirit away the daughter, Susan Witley (Suzan Farmer). Susan doesn’t want to leave her family, though, and Steven becomes increasingly determined to discover the meaning of all the weird goings-on. It all appears to be tied somehow to whatever caused the giant crater in the blasted heath just beyond the walls of the Witley estate.

Sohl’s screenplay takes the idea of “Colour Out of Space”, in which a meteorite causes a family to descend into madness and monstrosity, but strips it of its most effective parts. In Lovecraft’s story, the meteorite’s impact lets loose a force with a sinister, though unfathomable, purpose. It transforms the family ( a rural, uneducated bunch named Gardner) into loathsome, sickly creatures, when it doesn’t just drive them insane. Lovecraft's whole point is that alien life may not resemble terrestrial life at all; it may exist in something as intangible as a color. In Die, Monster, Die!, the meteorite still has transformative powers, but they come from everyday, unprejudiced, unconscious radioactivity. There is nothing particularly sinister about the rock – just what the monsters that the people affected by it become, which aren’t really terribly different from those in a dozen other science-gone-wild movies.

Having done away with the whole point of his source material, Sohl then drops what’s left into a plot structure lifted from Corman’s Fall of the House of Usher and The Pit and the Pendulum. Like these films, a callow young protagonist arrives at a dusty, decrepit estate to rescue a comely young woman from the madness of her family, only to meet resistance from a patriarch haunted by the sins of his ancestors. Sohl doesn’t even do a particularly good job of fitting his story into the template – the overwrought mentions of Nahum’s Satanist father, Corbin, are entirely vestigial and never become relevant to the plot. Although the film is set in the present day, locating the action in a Gothic castle-like mansion (one that includes a dungeon for a basement) makes the science fiction elements seem out of place. There’s one moment where Susan is attacked by a giant plant with mobile vine tendrils; it’s supposed to elicit suspense, but gets more of a “No, really?” response.

The apeing of the Poe series is somewhat appropriate when you consider that director Daniel Haller’s previous occupation had been as Roger Corman’s production designer. The Poe films always look like they cost much more than they did, largely because Haller had a knack for finding the right pieces to evoke grandeur and for getting those pieces for almost nothing. Both talents inform Die, Monster, Die!, as it turns out that skill in designing sets can transfer quiet handily to designing shots. Haller makes the beautifully put-together rooms of the Witley estate look magnificent, using 2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen (Corman’s preferred aspect ratio) and frequent applications of deep focus.

Unfortunately, while it all looks pretty, it’s also pretty been-there, done-that. There are a few good jumps (including an absolute beauty thirty-five minutes in, accomplished with nothing more than a single out-of-sync noise), but large chunks of the film consist of people walking down corridors, across rooms, and through dungeons. Haller has trouble making any of it really exciting. The scenes that do pop are the ones steeped in sci-fi – the sequence in the greenhouse of horrors and the climactic battle with an atomic monster – and that’s largely because their goofiness departs so greatly from the film’s typically staid mood that they shake us, momentarily, from our boredom.

Another welcome relief from the tedium is Karloff as the family patriarch. To say that he gives a fine performance is like remarking that giraffes are tall. He’s a consummate professional, through and through, giving his best to the material. It’s particularly impressive here because he is confined to a wheelchair for most of his time on-screen, which is not so much a character stroke as a necessary concession to the actor; Karloff was badly crippled by arthritis and emphysema at this point in his career, both of which greatly limited his mobility. It’s to the actor’s great credit that we never get a sense of mortal frailty from him, even though he was surely feeling it.

Something I should note is that there is a maddening visual distortion issue throughout the film, at least on MGM’s DVD. On the extreme left and right sides of the frame, the image is horizontally squeezed, which is a bit like watching the movie on a convex screen. The effect is most apparent when a character walks into the frame from one side (progressively widening as they near the center) or when the camera pans across the screen (the background becomes distorted as it “falls off” the edge of the frame). Both of these are common elements throughout Die, Monster, Die, so the issue is almost always visible. Whether this is a fault in the original production of the film or in the transfer to the DVD, I’m not sure, but I do know that the distortions are highly distracting, even slightly nauseating, especially on a larger television set.

I think the lesson that we can all learn from Die, Monster, Die is that Lovecraft is not Poe. We should not try to make Lovecraft into Poe. We should especially avoid doing it in cases where the Lovecraft story in question isn’t even vaguely Poe-like. There may be repercussions. I’m not convinced that the distortion problems I described aren’t the Great and Terrible Cthulhu subtly driving people insane for watching the film. Then again, he may not have counted on the fact that we’d probably be too bored to care.