Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

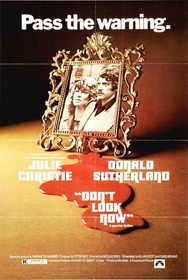

Don't Look Now (1973)

I dreamed last night that I broke a mirror, and among the shards, I found Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 classic Don’t Look Now.

Then, the dissonance hit.

A dead daughter, drowned in an English lake. Red, red, red. Two old sisters, one blind, one not, summoning premonitions, dead, dead, dead. Restoration. A dwarf serial killer. Red, red, red. The streets and canals and buildings of Venice. A dilapidated church. Dead, dead, dead.

Donald Sutherland. Julie Christie. Tucked in an emotional blanket of fear, anger, guilt, love, and psychic curiosity.

OK, I’m back, but I’m not sure I’ll ever be the same again.

Roeg’s portrait in London’s National Portrait Gallery is titled “al-jebr,” which in Arabic means, “the bringing together of broken parts.” Boy, does he do that well, even magically, with this strange film.

Based on a short story by Daphne du Maurier, the film unites Sutherland and Christie as John and Laura Baxter, a couple assigned to restore an old church along the exquisite canals of Venice. While in England, their daughter accidentally drowns in an estate pond before they leave for the continent, and while in Italy, Laura reflects on the tragedy. John has hurdled the emotional trauma, but when two elderly sisters offer premonitions to Laura in the most unexpected of places, the Baxters’ destiny becomes psychically complicated. Tensions bubble upon their relationship’s surface, and they misperceive themselves at the heart of a strange mystery. Navigating through the labyrinth that is both their minds and Venice, a setting made more bizarre by the underlying tale of a dwarf serial killer, the Baxters eventually find themselves in a surreal predicament.

Roeg’s editing work is masterful as he uses flashbacks and flashforwards to undermine chronology and disorient our most reliable of anchors: Time. Juxtapositions abound: the color red and broken glass; Venice’s fantastical, fluidic canals and its geometric architectural structures; the plot’s pertinent clues and deceptive red herrings; the Baxters’ predictable reactions and unpredictable responses; and their increasingly more bizarre perceptions and misperceptions all create an illusory world where dream is reality and reality is dream. The complex emotional spectrum shared by the couple, ranging from love, lust, passion, and curiosity to anger, indifference, distress, and fright, complements these contrasts.

Christie may be one of the most strikingly beautiful women in cinema history. And here, she doesn’t disappoint. On the surface, her reactions to the sisters’ premonitions seem absurd, but she cajoles us into believing her: the passion she exhibits for learning more about her deceased daughter is beyond convincing. Sutherland is equally excellent at cracking through the stoic cast that entraps his emotions. They share excellent symmetry: one passionate, reflective, and instinctive, the other cool, deliberate, and rational.

The ying and yang of their personalities unite romantically in what, at the film’s 1973 release, was considered one of the hottest sex scenes ever captured on celluloid. Legend has it the two actually did have intercourse during the scene, and the spontaneity of their lovemaking, combined with Roeg’s fine editing, was fueled by the impromptu nature of the scene itself: Roeg included the scene at the last minute to balance the tension and paralysis between them with some emotionally-charged drama.

Nominated in 1974 by the British Academy for Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) for seven key categories, Don’t Look Now challenges one’s traditional means of cinematic classification. The film leans more toward “creepy” than “horrific” and is more psychologically than viscerally frightening. There are shocks, but the film further defines fear by reopening old chapters about the human condition, which show us how intelligent, caring people can easily become disillusioned by regret, guilt, and loss. When this happens, they are susceptible to believing the most narcissistic of paranoid fantasies and therefore capable of foolish mistakes.

The film’s supernatural mood is medicated by its psychological dissonance. Nothing logical seems to unfold, yet we keep believing, keep questioning, keep engaging ourselves with the quirky plot. As John Baxter says, “Nothing is what it seems.” This elusiveness seduces John into pursuing the little “person in red” and Laura into believing the blind sister’s predictions. Roeg also weaves several oddities into the film’s visual and literary design to sustain the allure of this inviting headache: unusual bathroom encounters; the filmy, piercing orbs of a blind woman; close-ups of church architecture; rats crawling along the canal’s steps; a decomposed body hoisted from the water; etc. Since much of the film’s dissonance resonates from its outstanding camera work, it is no coincidence that cinematographer Anthony B. Richmond won the film’s only BAFTA award.

A staple in many of Roeg’s works, the film’s setting is pivotal, and Venice is the ideal locale for this cliffhanger. Throughout, the Baxters’ anxiety subtly conjures the “stranger in a strange land” mood that haunts so many foreigners. Although never oppressive, this motif pinches our nerves: the travel, the occasional language barriers, the longing for escape, the confused wanderings in the streets of Venice, and the marital tension these obstacles summon produce a mood of alienation that complicates the film’s already tense plot. Venice’s canals and streets are a geographical Rorschach test for the couple: the claustrophobic, impersonal, and weathered setting antagonizes them worse than their own psychological fallibilities. Cast in Pino Donaggio’s elegantly romantic and suspenseful score, which later became a trademark for Brian DePalma’s films, the setting is another formidable challenge for the Baxters.

Don’t Look Now is truly a gem: it’s elusive, eccentric, elegant, and invaluable. Approaching it, expect the unusual, and this exceptional yarn will inspire you to embrace that which is beyond natural, that which is, well, supernatural.

Trivia:

Renato Scarpa wasn't an English-speaker. He read his lines phonetically without knowing what they meant.