Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

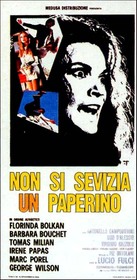

Don't Torture a Duckling (1972)

When done correctly, giallos have two components – a horror-thriller component and a mystery component. Lucio Fulci's Don't Torture a Duckling has neither. However, despite its failed attempts to muster the trappings of giallo, it is not bereft of intrigue. Rather than gory shocks and heart-stopping suspense, Don't Torture a Duckling is a brilliantly complex social commentary on the effects of mob mentality on a small town and the arrogance of modern thinking.

Children are being murdered in the small town of Accendura. As Italian police, as well as a few reporters, attempt to find the killer and stop these savage crimes, the town begins to fall into panic and paranoia. A number of suspects, mostly female, are paraded before us and yet, one by one, they are discredited and the kids keep dying. Finally, a small girl who doesn't speak may prove to be the key to mystery, but can our heroes get to her before the murderer?

If the story sounds kind of lame, it's probably because it is. Fulci attempts to create a complex mystery with a plethora of viable suspects – but he fails miserably. Our first suspect is Giuseppe, the village idiot, whom the murdered children were making fun of at the start of the film. This suspect is almost immediately discredited – he's not smart enough to make a viable suspect and he's apprehended in the first 30 minutes of the film. It wouldn't be much of a mystery if the creep was caught right off the bat, so it must be someone else. Our next suspect is Maciara (Florinda Bolkan), a local woman who is known for being a witch and being mentally unbalanced. She's also acting mighty suspicious, skulking around the most recent victim's funeral. Unfortunately, her time as a suspect is brief, being snuffed out when she, too, is apprehended by the police and confesses to killing the boys.... by witchcraft. While she may believe she is responsible for the boys' deaths, she is guilty of nothing but sticking pins in dolls. The killer is still on the loose. This leaves us with two more suspects – the obvious one, Patrizia, a modern “outsider”, and Dona Aurelia, the local priest's mother, playing the role of “so unlikely, she must be guilty”. Neither is particularly convincing, which makes the whole mystery of Duckling a bit of a failure.

It doesn't help that, aside from the dialogue and the character attentions, all non-verbal and incidental signs seem to read “Killer this way”. They're likely flashing in a garish red, as well. It becomes impossible at this point to discuss Duckling without spoiling the ending. If this bothers you, I suggest you move along. One of the first scenes of the movie, while the credits are still rolling, takes place in a church. The boys are praying halfheartedly, while a towering skeleton (I can only assume this is the church's relic) dressed in monk's garb watches over them. This, I will admit, is a tad suspicious. However, when the body of the first boy is discovered, the camera zooms in to show the priest's face, a picture of quiet sadness, as he performs last rites over the corpse. Roughly 24 minutes into the film, and we already have our suspicions raised. The second boy is found drowned in a pool of water, as if baptized. Finally, the the third child, and the only one we see prior to his death, is murdered at the foot of a giant, towering crucifix. Anyone noticing a pattern? If not, you may need to get your eyes checked, because all of the imagery is screaming religion and, attending to the body of every murdered boy is none other than our friendly, neighborhood priest. By the end of the movie, when the not-so-secret identity of the killer is revealed, we're not surprised to see a white collar staring back at us.

The final failing of Duckling is its lack of horrifying imagery. Over the course of the film, four children are murdered. Four. Of those four, we only see one immediately prior to his death, and the camera shifts up the lightning-bathed crucifix when the act occurs. In addition to being denied the gory details, we also only see the aftermath of two of the murders – one boy floating face-up in the washing pool, with nary a scratch on him, and the other face-down in the river, with a nasty contusion on the back of his head. Now, I'm saying I'm particularly excited to see mutilated children, but by relying on gossip about the murders to build suspense, the killer seems commonplace and non-threatening. Something horrific is happening in this town, but, because of how it is presented, the audience is left apathetic and disconnected. Without that visceral shock, which would later become Fulci's trademark, it's hard to really engage, ruining any chance that suspense and horror might have compensated for the mystery's failings.

However, despite its apparent shortcomings, Don't Torture a Duckling is still a very enjoyable and successful film. Oh sure, it's an abysmal failure when it comes to being a giallo, but Duckling also manages to do something few films accomplish: it is an effective and scathing social commentary. The most obvious indictment the movie makes it about the effects of mob-mentality and vigilante justice. It is notable that the most brutal and violent scene in this movie is the death of Maciara. Once she has been released from police custody, having been deemed innocent and mostly harmless, she is cornered in an old cemetery by several of the local townsmen. The scene is shot slowly, showing the men getting out of their cars, following Maciara, and methodically cornering her against a mausoleum. They take turns beating her viciously with chains and other implements, as rock music plays loudly in the background. The gore effects are brilliant, the camera lingering on Maciara's torn flesh with a careful caress that wasn't given to the dead children. Once she has been mutilated to near unrecognizability, she is left for dead. Crawling her way out of the cemetery, Maciara’s last moments are given the same loving care by Fulci's camera. The camera focuses on her frontally as she claws her way to the road, reaching out imploringly towards the camera and the audience for help. The camera shifts, and we watch the townspeople turn a blind eye and continue to drive on by as Maciara finally dies. There is a child murderer in the town of Accendura, but the killer is only one of many.

This particular theme is painfully obvious, even when considering just that one scene. When you then consider the rest of the movie in this context, it becomes apparent that Fulci is beating us over the head with the vigilante stick. The people of the town are constantly on the edge of riot, and turn from scapegoat to scapegoat. First, they clamor outside the police station, demanding that Giuseppe be turned over to them for justice – a man who is guilty of nothing but his own mental insufficiencies. Then there is Maciara, whose persecution is detailed above. However, while the townspeople rally for justice, supposedly in the defense of their children, the real killer walks among them, trusted with his victims’ care. The mob mentality, and the ensuing paranoia and hysteria, have blinded an entire town, turning what would normally be thoughtful, rational people into the very monsters they seek to destroy.

As if this theme were not heady enough, Fulci has another finger to point accusingly in Duckling. He has a few unkind words for the arrogance of modern thinking, and the disrespect outsiders have for traditional values. It is interesting to note that the murders did not begin until three boys witnessed the arrival of two prostitutes from Rome, the center of modernity in 1970s Italy. They were murdered to prevent contamination, to protect their innocence – something that would not have happened has the moral order been maintained. Further complicating the situation, is the Police Inspector in charge of the investigation, a modern thinker and an outsider. He is the one seeking out justice, the one who releases Maciara despite the pleadings of the local authority, the one who scoffs at such notions as witchcraft and religion. And yet, he is as responsible for Maciara. If not for his incompetence, perhaps the townspeople would have had enough confidence to trust in the authorities, rather than taking matters into their own frenzied hands.

The influences of modern ideas on traditional values as a detrimental force are also apparent in less-obvious forms. During Maciara's brutal death, modern rock music plays loudly, so much so that it almost dulls Maciara's cries of pain. This is a startling contrast to the rest of the soundtrack, which features more subtle, classical music. Another modern influence is Patrizia, the daughter of a mogul, living in the country to avoid a drug scandal. While she could be considered a force of good – she’s one of two people who eventually stop the killer -- she is shown earlier in the film taunting the priest, rubbing against him teasingly and asking him when he will be able to marry – something that she has obviously done before. Given that the priest’s motivations for homicide are rooted in physical desire, the need to save these boys from the wants of the flesh, this aggravation could be considered a contributing factor to his violence. Combine this with her taunting of Bruno (the third boy who is murdered), standing before him naked and teasing him sexually, it becomes clear that while Patrizia may have been a force of good in the conclusion, she has had a strong, deleterious influence on the town.

Don't Torture a Duckling is a mixed-bag. It's a completely fails at its obvious, stated mission – to be a successful giallo – but, simultaneously, it is interesting and intriguing if you are watching for more than just the mystery. While it is certainly not Fulci's greatest horror movie, I could say that it is one of his finer films. It is a subtle, but important, distinction.

This review is part of Lucio Fulci Week, the third of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

I just noticed "Nightworld:

I just noticed "Nightworld: Lost Souls" is very similar