Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

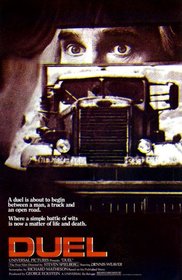

Duel (1971)

Too many film critics find joy in bashing Steven Spielberg. I am not an ardent fan of his, but his genius and love of cinema exceed the majority of those in Hollywood. Anyone who can claim directorial rights to Jaws, Schindler's List, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and E.T. is, to put it mildly, okay in my book. And yes, I have seen several of his films, and I have enjoyed many. But to truly appreciate Spielberg's talents, one should visit his 1971 closet classic Duel. Released as a television movie and produced on a shoestring budget in two weeks, Duel resonates with the sparks of genius that have lit the fire illuminating Spielberg's Hollywood journey. The film also reminds us that Spielberg was once a member of that Rat Pack of audacious, experimental directors who defined the American New Wave and included chic Hollywood Hall of Famers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorcese, Peter Bogdonavich, and Robert Altman. The precursor to John Dahl's Joy Ride and other road rage vamps, Duel is a wonderful glimpse into the mind of Spielberg minus the monolithic budgets, extravagant sets, and mind-numbing technology. The guy can make an intense film without these toys, something too many of us forget, and something too few of us ever realized.

Interestingly, Duel lured Spielberg out of film school. Working in the mailroom at Universal while attending film classes at California State University at Long Beach, Spielberg accidentally stumbled upon Duel's script; he begged Universal's chiefs to direct it. Subsequently, he never finished college to earn his degree, and the rest is history. The script, written by Richard Matheson of "Twilight Zone" fame, was originally a short story in Playboy. Matheson adapted it into a teleplay, although Universal execs wanted to make Duel a major film, but when Gregory Peck declined the role later assigned to Dennis Weaver, they decided on television. CBS agreed to air Duel as a Saturday Night Movie. It received excellent reviews, but when the film was released overseas a few years later, Spielberg was required to add an additional 20 minutes or so of footage and some profanity to Hollywoodize the 74-minute original.

For Spielberg, Weaver was an obvious choice. His role as the paranoid Mirador Motel Night Manager in Orson Welles's film noir classic Touch of Evil was, according to Spielberg, a perfect match for Duel's protagonist, David Mann, who experiences in this film a much more prolonged bout with anxiety. Weaver does a nice job of weaving (sorry) in and out of arrogance, panic, terror, revenge, anger, foolishness, and triumph. He is believable enough to taste the evil truck driver's bait and foolish enough to continue nibbling.

The plot here is simple. Duel is an allegorical quasi-silent film about a salesman, Mann, driving through rural California on a business trip. Suddenly, he finds himself randomly stalked by a homicidal truck driver. His voyage is punctuated by pit stops that include minimal dialogue and become increasingly more suspenseful. Mann stops at a diner for lunch, a roadside checkpoint to help a bus full of children, a filling station for gas, and a railway crossing to allow a train to pass. At each stop, additional layers of drama compound the horror created by the truck driver.

Both vehicles are important characters. Mann's car clearly has a point of view, which is immediately understood in the establishing shots when the camera is placed on its hood. We see the road from the vehicle's "eyes" and not Mann's. This suggests there are "rules of the road" existing outside human thought. As Mann exits the city and enters the desert, his car's point of view will be defined further by those rules. Like the face of a boxer at the end of a grueling match, the truck equally pummels Mann's vehicle. But his antagonist's truck is full of even more character.

The fuel truck is grungy, greasy, and old, reminding us of something from another world. Its yellowish hues are symbolic of sickness, and its sandy hues suggest it emerged from the soil in the surrounding cliffs and mountains. Subsequently, the truck is a mutant product of nature full of wild instincts. The word "FLAMMABLE" is written on it, which foreshadows its potential for chaos. As Spielberg points out in the "Bonus Features," the truck had a face complete with eyes (front windows), pupils (headlights), nose (front grill), and mouth (front fender). Even the license plates have a role: they represent "notches on its belt," Spielberg explains, for the states it has conquered. Throughout the film, the truck looms like a demon on the desert horizon. The truck is shot to make it appear monstrous and human. When under a bridge obscured in shadow, the truck explodes into life with the flickering on of its lights, which clearly resemble the eyes of an awakening monster. At another point, a low-angle shot captures Mann's vehicle between the truck's tires, which resembles the spread out legs of a giant. And because the film sparsely uses human dialogue (Weaver speaks only a few hundred words; the truck driver says nothing), both the car and truck "speak" more often than the people.

Spielberg fills the film with effective cinematic props. Here we are in the hands of a master learning his trade and playing with his tools. When Mann enters the diner after crashing into a fence, a voice-over emerges to represent Mann's internal monologue. Here his voice reveals panic and concern, especially since he knows one of the patrons is the truck driver who just tried to kill him. But Spielberg quickly returns to silence, and it is this silence which helps trap us in the web of Duel's paranoid fantasies. The film is full of minimalist angst; we are sucked in, like the protagonist, to its sparse features. When Mann stops at a railway crossing and finds the truck seeking to run him into the passing train, the scene ends ironically with the ambient sound of birds chirping. This auditory contrast is striking. The film is also full of effective foreshadows, none more useful than the failing radiator hose, which Weaver dismisses during his first pit stop, but which naturally causes his car to fall apart near the duel's conclusion. The choke shots of Weaver in his vehicle toward the end of the film cross cut with the car's dials and knobs are also excellent.

Spielberg expertly builds suspense in the spirit of Hitchcock through omission: what we don't see or know causes as much suspense as what we do. We never see the truck driver; we only see his body parts, which suggest a fragmented personality. We have no idea why he wants to kill Mann. We don't know much about Mann either, other then he is married, has two children, and his wife claims she was sexually harassed by his colleague. We don't know where exactly they are except somewhere in Southern California. We don't know which diner patron is the truck driver, but we know he is one of the six cowboy patrons. Spielberg also has fun, particularly when the truck smashes into a telephone booth Weaver escapes from while calling for help. The gas station here doubles as an exotic animal farm. Besides the booth, the truck smashes several reptile exhibits; naturally, Weaver has to dodge the truck AND two other dangerous creatures: a rattlesnake and tarantula.

The allegory in Duel is something Spielberg leaves for us to decide. By not revealing much about the characters or their conflict, he paradoxically breathes life into them because they represent primal tensions between city and country residents and white- and blue-collar workers. Two other conflicts emerge as well: business vs. industry and man vs. machine. However, determining their messages is confusing. These tensions collide into an allegorical Armageddon that literally ends on the side of a road. Mann clearly represents humanity, and subsequently, defeats the machine, yet he needs a machine (his car) to do so. Throughout the film, there is a "don't mess with rednecks" mentality, yet the film ends bleakly for the redneck truck driver. If the businessman, city dweller, white-collar worker seems displaced in the country, he does a good job of navigating through the pitfalls of the American West. If he is being satirized as weak and vulnerable when out of his element, he sure is heroic in the end. The film loses steam when considering these conflicts.

Nevertheless, Duel is a good film certainly worth your time. The movie revels in nostalgia and takes viewers back several years: to 1971 and the historical context in which it was made; to the beauty and allure of silent films and the power of letting images do the talking; to the early part of one of Hollywood's leading men; and to the wild West, when duels were standard fare for a man of any occupation. If you want a hell of a ride, check this one out.

Trivia:

The name of the bug exterminator that Mann mistakes for a cop is Grebleips - "Spielberg" backwards.

Footage from the film was later used in The Incredible Hulk TV series - incensing Spielberg, and causing him to demand footage usage clauses in all of his future contracts.

My compliments to review

My compliments to review author, Chris Justice - this is the best review/essay I have ever read on Spielberg's psycho-drama Duel. Great insights - you get inside this movie's "head" - very well done !

My theory (which I can't

My theory (which I can't believe I haven't found on any reviews) is that Mann is paranoid delusional and the truck is all a figment of his imagination driving him to destruction. All the destruction in the movie happens by the hand (or car) of Mann with the exception of the phone booth and the first terrarium which was witnessed only by Mann who was then shown getting up from the ground in the midst of broken glass and animals. The storekeeper ran in screaming about her animals, but with no care about the truck, from then on, we see Mann throwing the remaining cages at the truck. The wierd scene with the school bus is also a delusion tipped off by the illogical behavior of the bus driver -- thinking the Valiant could push-start the bus, being unconcerned about the children playing on the side of the road, and rolling a busful of kids downhill without power.

My wife doesn't buy my analysis, but I was thinking Mann was crazy from about the point of his conversation with his wife,

Astonishing film. critically

Astonishing film. critically underrated.

Our HERO exhibits traits of

Our HERO exhibits traits of AvPD.. Avoidant Personality Disorder aka Beta Male!

1) The Diner scene when the waitress asks him if he needed anything else other than the sandwich.. he says no thanks and then when she walks away...then he says ketchup which she was not able to hear.. He CANNOT demand!

2) Could not say "No" to the school bus driver when he asked him to push the bus

3) Making rash decisions: He asks the school bus driver not to sit on his car hood lest he damages it but once he sees the truck appear across the tunnel he himself starts jumping on the hood to let his car loose from the bus :)

4) His wife dominates him

5) He did not confront the guy who was hitting on his wife at the party..His wife humiliates him for his inaction by saying that the guy was "raping her" in front of everyone.

6) He apologises to his wife even though his wife doesnt want him to apologize. Women want MEN to act like MEN! Some men dont get that!

7) He has children at home .. yet he does not know how to handle kids.... (the school bus kids)

8) In panic he loses sense of his surroundings.. two times he pulls up on the wrong side of the gas pump..and he was sleeping beside the railway track and didnt even know about it...

9) In the second part when the gas attendant tells him that his radiator hose (which goes Kapoot when climbing up later on) needs to be changed he replies that he would have it changed later on. TO this the Gas Attendant says "You're the boss!" The man replies "Not in my house I'm not"

10) At the Diner instead of confronting by asking who is the truck driver.. he just keeps on looking at boots and keeps on guessing.. again avoiding confrontation...

11) when in part two of the video on youtube, he first pulls at the gas station he did not have the courage to confront the truck driver as to what the hell is he trying to do??

12) The truck driver took this as a cue that he could play with this guy since he doesnt have the balls to confront him even though he overtook him dangerously

13) His body language screams BETA! When he is calling his wife to tell her where he is (what an obedient husband) he puts his hand in his pocket (That is a SO BETA) when addressing the operator. Also he keeps his hand in his pocket while talking to his wife.. Also when he finally confronts one guy in the DINER to "Cut it out" he has hands in his pockets...remember kids putting your hand in pocket while conversing with someone is a sign of insecurity/weakness. Never do that!

14) The talk show on the radio talks about a loser who is dominated by his wife (He is afraid of filling the census form since the head of the family is not him but rather his wife).

15) At the end of the movie he finally takes on the truck HEAD ON! He finally Confronts his fears!

16) You will do much less damage if you confront things right at the beginning when trouble starts appearing.. You will lose a whole lot more if you confront in desperation later on...(a hint was also given about this when his wife tells him about how the other guy was hitting on her at the party..To which he replies that she wanted him to have a fist fight with him to which she says NO..She just wanted him to be a man. ..again he is taking things to the extreme instead of having confronted the guy at the party to stop hitting on her he thinks that the only way to stop him is to fist fight the next day. He is using something called "Projection" here since he is projecting his fears of having a fist fight onto his wife that she wants SO! She never wanted him to fight.. All she wanted was for her husband to stand up for her) This is what women want.. A Woman doesnt want Mr Olympia; She wants a man who stands up for her .. it doesnt matter if he gets beaten up to a pulp.. She will love him even more coz he stood up for her, being victorious or getting beaten doesnt matter in his woman's eyes! All that matters to her is that her man stood up for her! THATS IT! Remember this kids!

If he had confronted the truck driver right at the first time they stopped at the gas station, the truck driver might have behaved. Since he failed to confront him the truck driver took it us a cue that he could bully him and play with him.

Lesson: Jo dar gaya woh mar gaya. Your first impression will dictate how people treat you later on... Whether it is your office or home or out on the streets...this applies everywhere..

What is this movie all about?!?! A Man conquering his insecurities!

The radio/talk show represents his conscience of which he is unaware..(dominated by his wife.. He has serious insecurity issues/ avoidant issues)

The truck is the microcosm of his world of challenges and insecurities... His car represents his weak will and subservient attitude... The Duel is between them....

Lesson: Your purpose in life doesnt lie in avoiding problems.. You have to confront them HEAD ON!!!

I watched and analysed this

I watched and analysed this film for a university essay and I came up with the exact same theory as you! I have found no one else who agrees with this which is odd because I honestly thought this would be the 'accepted' theory for this film.

I'm glad someone else feels the same way.

I don't know that it was a

I don't know that it was a fact the truck driver was in the diner.

It seems assumed so, but for all we know the driver might have stayed in his truck, having used the stop to rest up.