Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

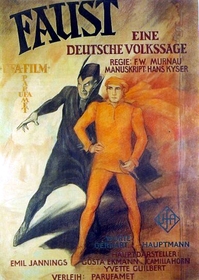

Faust (1926)

Before Regan MacNeil, Damien Thorn, and Louis Cyphre, there was Mephisto, short for Mephistopheles, Satan’s most notorious alter ego. Satan and his sentinels have captivated creative souls’ imaginations for centuries, but few artists have manifested those visions as powerfully as F.W. Murnau did in 1926. After a staggering six months of production and two million marks, Murnau’s Faust is one of horror’s most visually stunning cinematic nightmares, an archetypal tale of love, power, morality, temptation, and redemption that sizzles with passion hotter and redder than the Devil himself.

Few horror classics have relied upon such lofty source materials. Murnau’s Faust draws upon an amalgam of high-brow sources: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust; Christopher Marlowe’s play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus; Pietr Brueghel’s 16th Century painting “An Alchemist at work”; Rembrandt’s “Faust”; and other German folklore and myths. Some scholars, most notably the famous German film historian Siegfried Kracauer, have argued that Faust thoroughly distorted the archetype’s subject matter and stripped the story of its most important themes; others have hailed Murnau’s version as a refreshing new treatment of this ubiquitous narrative.

The success of The Last Laugh, Murnau’s previous film, offered him opportunities to creatively explore. Combined with the enormous success of Eric Pommer’s German movie machine, the Ufa, Murnau and other German directorial stalwarts such as Fritz Lang were afforded a unique opening (Lang capitalized on these opportunities with the classic Metropolis, also released in 1926). As Michael Koller writes in Senses of Cinema,

“Both Faust and Metropolis were the apotheosis of Eric Pommer's and Ufa's overreaching ambition to create an international market for German cinema. Completed within four months of each other, these prestigious productions were at huge cost, featured internationally recognized casts, and were made to demonstrate the technical sophistication of German crews. The large budgets allowed Ufa to purchase innovative equipment and the completed films premiered in Ufa's newest cinemas allowing them to showcase these new venues.”

However, Faust was Murnau’s last German film: after its release, he was lured to America and seduced by the Fox Film Corporation’s founder, William Fox, to direct another classic, Sunrise. Ironically, Murnau died in a car accident in the California sunshine after Sunrise’s release.

Faust begins with a confrontation between Mephisto and an angel that prompts this bet: Mephisto wagers he can ruin the elderly alchemist Faust. When the angel agrees, Mephisto summons a plague to wreak havoc on Faust’s village. The benevolent alchemist wants to cure his neighbors but cannot; his failures force him to question religion, so Faust turns to blacker magic and asks Mephisto for help. For his assistance, however, Faust must with Mephisto sign a contract. When villagers learn Faust collaborated with the Devil, they stone and ostracize him. Disenchanted, Faust accepts another contract: sell Mephisto his soul, and Faust will earn eternal youth. Mephisto lures an Italian duchess to fall in love with the youthful, virile Faust, and the alchemist extends his contract over his lifetime. He’s now Mephisto’s forever! Returning home, Faust falls in love with another woman, Gretchen, but Mephisto turns her brother against Faust and dupes Faust into appearing as his murderer during a sword fight. Gretchen later has Faust’s baby, but the baby meets a cruel fate, and she is accused of the crime; Gretchen is sentenced to death, and Faust makes a difficult decision about his own fate. When Mephisto returns to the angel to claim his winnings, the angel delivers bad news.

Faust’s narrative mesmerizes viewers with its binary themes, tragic irony, and epic scenes. Laced with contradictory motifs that convulse one’s intellect, Faust pits bodily pleasure vs. intellectual obligation, the visual vs. the literary, health vs. disease, light vs. darkness, heaven vs. hell, and good vs. evil. Paced with dramatic crescendos that tighten one’s nerves, Faust resolves its histrionics with bleak existential ponderings. Overwhelmed by the sheer audacity of its visuals and disoriented by its philosophical contradictions, Faust’s oppositions paradoxically provide viewers a haunting clarity: no space, visual or intellectual, is left for middle ground, and no relative morality breathes; you’re either with Mephisto or you’re with Faust, each a stark allegorical figure representing evil and good.

Notwithstanding its complex philosophical themes, something primitive lurks within the film’s soul. Occasionally, it resonates like a bad dream returning us to primitive, child-like impressions, stark authority figures, simplistic either/or realities, instant gratifications, and the alluring charms of temptation. Faust reminds us that some dreams and desires please too eagerly. It prods us with simple, grandmotherly clichés such as “be careful what you ask for” or “the devil made me do it” but within a multi-textured and layered context that resembles a parable. Experiencing the film is like embracing a painful contradiction.

Underlining these tensions is the tragic irony that the society Faust saves punishes him for his satanic collaborations. We share the luxury of knowing Mephisto’s plans, but Faust tragically doesn’t, and this reality undermines Mephisto’s antiheroic qualities. When paired with Faust, Mephisto appears the practical, seasoned negotiator, the ultimate salesman willing to deal; however, when alone, his evil bubbles to the surface, disclosing his Machiavellian intentions. Because we know what Faust doesn’t, we simultaneously shutter at and sympathize with his temptations. When Mephisto’s anti-antiheroic personality is cast within the film’s epic scenes – his appearance, his flight over the city, and later, the ride on his cloak with Faust into a fantasyland of strange birds and surreal music – a hypnotic movie is at your knees.

The film’s international cast was a deliberate marketing tool designed to appeal to international audiences, and its casting history brews with peculiar twists. The legendary Mary Pickford was slated for an earlier American version, but her mother refused to have the silent film icon cast as a mother who strangled her baby. Also, Lilian Gish, another silent film vixen, was initially slated to play Gretchen, but her popularity instigated unusual on-set demands such as using her own photographer, so Murnau refused to accommodate the prima donna.

Among the many stellar performances, Emil Jannings’s depiction of Mephisto excels. His serpentine tongue, wide eyes, and geometric eyebrows constantly lure us into his face, and his facial expressions are an inferno of acting acumen: from haunting to humorous, devilish to debonair, and cunning to contrite, he IS the Devil, always looming in the background like evil itself. His performance reminds us that the clarity of evil has never appeared so convincing, especially since he appears to Faust as human and not some supernatural demon.

Murnau may not have been the first to employ elaborate set designs, expressionist lighting techniques, meticulous costume designs, or moving and subjective cameras, but he was one of the first to master each and weave them together into a cinematic tapestry unrivaled in early, or for that matter contemporary, film. As a celebration of the visual over the literary, the film seduces us with its images, and its visual design is palpable. Murnau used two cameras for most scenes, and the special effects such as pyrotechnics and use of miniature models were sophisticated for 1926, making the film as much a fantasy as horror masterpiece. The symbolism of the film reminds us that what we see is as powerful and communicative as what we do, say, feel, and think. The four horsemen, the moon, the hourglass, the eyes, the Virgin Mary iconography, and the skulls and skeletons remind us of the film’s universality.

So much of Faust burns with bravado and daring. The film can easily be interpreted as a critique of capitalism with its financial jargon (pacts, contracts, free trials, etc.) and message that covenants with unethical figures ultimately produce personal and communal ruin. That such a subtext was percolating in a global culture that was beginning its love affair with capitalism is impressive. The film also boasts a nude scene that must have shocked some viewers, and another sexually charged episode depicting Mephisto groping a woman’s breasts. In fact, a weird eroticism complicates the relationship between young Faust and Mephisto: Faust says he is Gretchen’s forever, which means, unknown to Faust, that she is also vicariously playing the role of Mephisto. He willingly succumbs to her while unknowingly must surrender to Mephisto. Additionally, its brazen depiction of Satan, his defiance of conventional morality, and his celebration of atheism are unnerving even for today’s standards; for 1926, such ideas were revolutionary, particularly during a time when much of Europe, notably Germany, was experiencing social, cultural, and political revolutions. Talk about adding fuel to the fire!

Faust is like a map outlining the geometry and topography of our soul’s darkest states. Legendary director Fritz Lang reportedly said during his eulogy at Murnau’s funeral, “It is clear that the gods, so often jealous, wished it to be thus.” Murnau may have upset those gods with this hauntingly seductive portrayal of the war between good and evil waging within us all. If you’ve ever battled with that chorus of discordant voices screaming in your ear before Temptation reared its sexy body, Faust is a must-see cinematic experience. Whether you or Temptation ultimately claimed victory, like Faust (and Mephisto himself), remains to be seen.