Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

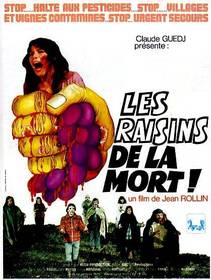

The Grapes of Death (1978)

In an era of mainstream PG-13 horror, it's thrilling to delve back into the European erotic horror films of the 60s and 70s - films that gained their reputations by offering highly provocative images, if often at the expense of story. One of the most controversial filmmakers in this vein is Jean Rollin, best known for a series of surrealist vampire films that began with Le Viol du vampire (The Rape of the Vampire, 1968). In their best moments, these films offer images and scenarios worthy of Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali; Rollin strips vampire films (as well as voluptuous actresses) down to their essence - giving us a pure, strange and haunting beauty unencumbered with intellectual agendas.

The Grapes of Death was Rollin's first attempt to do the same for the zombie subgenre. It begins, much like Tombs of the Blind Dead (1971), with two women and one man on a train ride through the countryside - in this case, the stunningly beautiful mountain region of Cevennes in France. One woman hastily gets off the train and ends up among gothic ruins, where she is attacked by the living dead. The plot isn't much more complicated than that, which is actually somewhat refreshing for a Rollin film. The story is very straightforward, but nevertheless boasts the director's personal touch. What's most interesting is Rollin's nuanced interpretation of horror's most historically marginalized monster.

At the request of producer Claude Guedj, Rollin originally set out to make a disaster film along the lines of The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Earthquake (1974).1 Perhaps anticipating budgetary problems, they opted instead for a variation on Night of the Living Dead (1968). As Jamie Russell explains in his history of zombie movies, Book of the Dead, the success of Romero's landmark film didn't really bring the zombie movie into vogue. There were a few other comparable successes - including Tombs of the Blind Dead and Bob Clark's Deathdream (1972) - but the subgenre remained largely unexplored until the release of Dawn of the Dead ten years later. Rollin's film was made before the release of Dawn, which is probably the reason that it stands apart from so many of the zombie films have come along since. In fact, it bears closer resemblance to Romero's recent Diary of the Dead (2007), in which the characters remain constantly on the move rather than barricading themselves against the apocalyptic threat.

Rollin's concept of zombies was that they would be, like his vampires, pitiable creatures. In The Grapes of Death, the zombies lapse in and out of consciousness and are, at times, aware of the awful things they are doing. In one instance, a dead man pins a naked blind girl to a door and saws her head off. Later, when he realizes what he's done, he apologetically kisses the decapitated head. An equally striking example of erotic horror comes when a semi-nude girl is run through with a pitchfork. This particular makeup effect works far better than the rapidly decaying flesh on the zombies. Allegedly, the extremely cold temperatures are to blame for the unrealistic look of the zombie makeup2... and almost prevented another stunning visual from making it into the picture. According to the director, porn star Brigitte Lahaie was so cold during the filming of her nude scene that she literally couldn't speak her lines.3

The Grapes of Death offers another interesting variation on the post-Romero zombie mythology. As the title implies, the cause of the zombie infestation is traced back to a vineyard, where an experimental pesticide has infected the wine. Echoing Romero's work in The Crazies (1976) as well as the Dead series, Rollin and screenwriter Jean-Pierre Bouyxou express ecological concerns as well as vaguely political ones. When the cavalry arrives (in the guise of two beer-drinking rednecks who don't hesitate to shoot their infected friends), they spout off about the peasant's role in revolution. The last infected survivor later explains that the outbreak only spread because the vineyard employed "illegal immigrants" and the owners were therefore afraid to call the police. The simple fact that the majority of the action takes place in a vineyard also provides an oblique connection to the pre-Romero zombie tradition: bacchanalian revelry is linked with the creation of zombies, just as the out-of-body ecstasy of the voodoo dance was linked with their creation in the poverty row zombie movies of the 1930s and 1940s.

For dedicated fans of the subgenre, this film is a real treat. It's not hard to overlook cheap effects and choppy editing when there's so much to appreciate: natural gothic beauty and alluring sexuality, fused with solemn yet straightforwardly entertaining purpose. It's certainly not everyone's cup of tea, but for a handful of horror fans this is fantastic pop art.

I will start of by pointing

I will start of by pointing out the obvious: THIS IS NOT A ZOMBIE MOVIE. No one rises from the dead. Rather, this is Rollin's screed against bourgeois values. The message is quite plainly encapsulated in the discussion between the two "rednecks". The older one who fought against the Germans as a partisan in WWII is implied to have been a communist, and the younger is clearly an anarchist. The catastrophe which befalls the village is to be blamed entirely upon the entrepreneural modernization of the winery. From the experimental (illegal) pesticide to the artificial aging vats to the exploitation of Soviet Bloc refugee labor, the absentee vintners are morally bankrupt cads who care for nothing aside from profit. Rollin non-depicts them as an unseen alien presence damaging the character of French rural culture and tradition.

The comment above is

Strictly speaking, actual

Strictly speaking, actual "zombies" do not rise from the dead . . . their brains are destroyed by drugs so they can become a form of cheap labor. So in a sense, Rollin's zombies are closer to the real thing. Otherwise, good point about the political allegory, implicit in most zombie movies but much more explicit here