Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

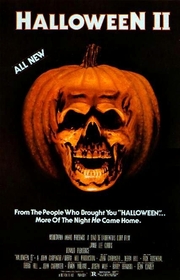

Halloween II (1981)

Halloween is one of the most subtle and effective horror films ever made. Frightening and intriguing, it leaves a lot of questions to which we have very few answers, especially concerning the invulnerability of Michael Myers (or, more accurately, “The Shape,” as he is called in the credits). Halloween II is an attempt to explore these questions. Through camerawork and dialogue, the film analyzes the Shape as he continues to wreak havoc, picking up where the first film left off. Because this means we must focus more closely on a murderer whose horror comes primarily from our inability to see him clearly (or at all), Halloween II is not quite as scary as the first, but it does illuminate the nature of the Shape and thereby nature of evil.

The film starts with a short courtesy rewind to the very end of Halloween, just in case we’ve forgotten how it ended, before moving onto the events that take place later that same night. Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) is taken to the hospital for knife wounds sustained by the Shape, who is still out to kill her. The Shape continues to terrorize the neighborhood before making his way to the hospital to finish what he started. Of course, there are human obstacles along the way, which he dispatches as effortlessly as ever.

The Shape himself has lost very little of the horror he wielded in Halloween. Since his first kill as young Michael Myers, he has been infinitely patient, stalking his victims and waiting for the perfect moment to strike. He hasn't changed in Halloween II. Often, instead of attacking his victims, the Shape just stands there, watching and waiting, not even trying to get closer. During a particularly noteworthy scene, the Shape sees one nurse, then another, coming down the hall. Instead killing them, he hides in a room (full of newborns, no less), and watches them go by. It isn't until later, when the moment is right, that he finally murders them. Dr. Loomis, his psychiatrist from the mental institute, understands the Shape's patient nature, stating that Michael simply sat and waited fifteen years after his first murder, before making his escape to go after Laurie. Highlighting this concept is the playing of George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in a few parts of the film. Like the slow-moving, blood-lusting zombies, the Shape is a killer who is in no hurry and does not seem to care how his victims are killed (though sometimes the ready-at-hand murder method also happens to be fairly original, such as in the I.V. bloodletting scene). The killer who revels in destroying bodies in mind-boggling ways does not seem quite as sinister as the the one who only cares that the job gets done.

The horror of murder lies much more in the apprehension of slow, methodical pursuit than in the shock of fleeting kills. When a murder takes place, all the built-up tension is released. The moment may be awful, but the worst is over, and we, like the victim, can rest. However, when we know a monster is out to kill but is waiting for the perfect moment, the tension builds even when the threat is not on camera. Director Rick Rosenthal, like John Carpenter (the director of the first Halloween), understands this, and uses it to his advantage, positioning both the Shape and the camera for maximal fright. Since the Shape’s intent to kill was established in Halloween, seeing him merely standing in the background has always been alarming. While he may only been seen fleetingly, we realize that he has always been close, even when we couldn't see him. Rosenthal uses this scare tactic well, particularly in the hospital, where he places an empty background, such as a hallway or an open door, into almost every scene. This creates an environment in which the Shape could appear at any moment. Along with the Shape’s patient, methodical character, Rosenthal's camerawork perpetuates our anxieties and heightens our fears.

Unfortunately, this film also uses some cinematographic techniques which stray from Carpenter’s methods, marring the experience. One way the first movie used the Shape’s haunting patience to its advantage was by showing him standing plainly in view, then cutting away for a second, and looking back only to find him gone. This technique was effective because what’s more unsettling than seeing a killer right in front of you is knowing that he is probably somewhere close but not knowing where. These types of scenes are gone, making the experience of Halloween II less unsettling than its predecessor. Instead, we see the Shape on the hunt. Never before had we seen him in active stalk mode, unless it was because a character was watching him. This time, however, the camera doesn’t separate itself from these moments. It often hovers behind him or watches him from a security camera unseen by the characters as he moves to his next destination. This puts us inappropriately into the Shape’s own subjective experience, an experience which should be entirely un-relatable. These stylistic changes, which give us a more in-depth perspective of the Shape, take away from the horror of being stalked. We are in the Shape's shoes, not the victim's, and it's far less terrifying.

The problem of perspective pervades other cinematic elements of the film. Once Halloween II gets past the quick rewind, there is an “opening” tracking shot from the Shape’s point of view, just as in Halloween. It is a fun way of experiencing the events immediately following the attack, but it is stylistically inconsistent with our understanding of the Shape. Ever since Michael Myers’ first kill as a child, he became inhuman, a shape rather than a person. That is why we never went back into his perspective in Halloween—we had absolutely no way of relating to the character. In the context of what the character has become, it is unfitting for the camera to give us these first-person perspectives.

Though the film loses some of the scare factor as a result of direction, it does offer more in the way of understanding the Shape's mythology. Significantly,Halloween II elaborates on the first film’s claim, which was made almost in passing, that the Shape is pure evil. At one point in Halloween II, Dr. Loomis states that there is neither consciousness nor reason, “nothing even remotely human,” within the killer. Evil has no psyche; it just stalks, scares, and kills. This lack of human quality would seem to confine the Shape to the subconscious, perhaps even a part of our own subconscious. This gives new meaning to those startling moments when he walks in from behind the camera, almost as if from within the viewers themselves. Evil also cannot be killed, and the Shape’s invulnerability is reconfirmed when he again survives gunshots to the face. Later in the film, further demonstrating his unstoppable nature, the Shape shatters a glass door just by slowly walking through it. You can stall evil and even stun it, but it will always get back up and come after you, despite what obstacles lie in the way. These moments clarify what was insinuated at the end of the first Halloween: The Shape is inhuman. What was once a disturbed child has become a supernatural being with absolutely no residual humanity.

Halloween II is indispensable to the Michael Myers / Shape story. While not as good as the first film, its contributions to the character are important, and it still provides some good scares along the way. Halloween gave us horror in a style unlike any other. Halloween II analyzes that horror, but to do so, it has to drop some of the panache.

Great review! Halloween II

Great review! Halloween II is my favorite film in the original franchise after Part 1 and light years ahead of its utterly dreadful 2009 "reimagining".