Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

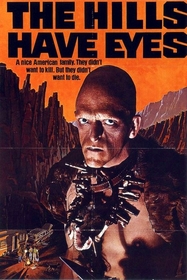

The Hills Have Eyes (1977)

It's hard to imagine another writer/director responsible for so many of horror's highest highs and lowest lows as Wes Craven. Take a look at his resume - this guy doesn't tread a lot of middle ground. The man who altered horror's landscape with A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream is also responsible for regrettable duds like Deadly Friend, Shocker and The People Under the Stairs. His first film - 1972's Last House on the Left - was an inept, mean-spirited mess that seems to owe much of its fearsome reputation to word-of-mouth from people who haven't actually seen it. His next, however, would be a milestone in the decade that really saw low-budget independent horror films come into their own.

In a recent interview, Craven touted Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as remaining unmatched for sheer intensity and nihilism, and I'm inclined to agree. Craven's sophomore effort The Hills Have Eyes has a lot in common with Chainsaw in terms of plot and setting: road-tripping city folk have vehicle problems, get stranded in unfamiliar (read: rural) territory and become prey for a family of inbred cannibals. Given the subject matter and period, such comparisons are unavoidable. And yet Craven's film is by no means a pale imitation - in fact, it's testimony to his talents that Hills stands so confidently apart from what may have been its chief influence.

Hills has a Cleveland family - retired cop and wife, two daughters, son, older daughter's husband and baby daughter, plus two German Shepherds - stranded in the Nevada desert after an ill-advised detour results in a snapped axle on their station wagon. They prepare to hunker down for the night in their trailer, unaware that they're being watched. Before the sun comes up again, three of them will be killed and the baby will be abducted; the survivors find that their only course of action is to meet savagery with savagery.

When he's "on" - as he is in roughly half his films - Craven often rivals John Carpenter in his uncanny knack for cultivating an all-encompassing atmosphere of hopeless dread long before he unleashes the monsters. As the desert landscape slowly darkens in Hills, we've barely been given any hint of what horrors lie in wait for this family, and yet we're certain that a long, violent night looms ahead.

In Chainsaw, director Tobe Hooper employs primitivism to such an extent that his film feels almost like a documentary; Craven's film certainly shows its budgetary constraints but it's much more conventionally cinematic. Its only serious problem is a common one among horror films from this era: the protagonists are so sickeningly wholesome (with the bible-thumping matriarch being particularly detestable) that they're a lot less interesting than the villains. Good Family versus Bad Family makes for an intriguing set-up, but it's unfortunate that Craven wasn't able to give his main characters a bit more depth. This problem is compounded by the fact that the most memorable performances come from the cast of baddies as well (particularly James Whitworth and Michael Berryman).

In terms of ideology, Craven's film is actually quite a departure from Chainsaw since Chainsaw's victims aspire only to escape their tormentors rather than fight back. By contrast, Hills asserts (quite credibly) that even the most decent and mild-mannered people are capable of horrific acts of violence when pushed far enough, an idea that echos Sam Peckinpah's masterpiece Straw Dogs, not to mention vivid memories of Vietnam, wounds still fresh in the psyche of 1977 America. Of course, it's hard to ignore the impact that the murders of northern civil rights workers in Mississippi a decade earlier had on popular culture in general. Whether the reference is overt or subconscious, it's evident in Hills, Chainsaw, Straw Dogs, Deliverance, Easy Rider and many more films from the decade or so that followed the real-life atrocity. And the message is clear: you're out of your element here. Better watch your back.