Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

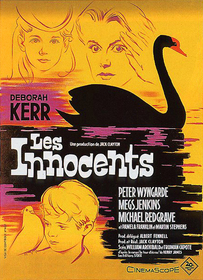

The Innocents (1961)

It's interesting to think that, with over a century of movie-monster history, one of the scariest creatures to grace the screen is still nothing more than a small child. Despite leaps and bounds in make-up and special effects, the sound of a young girl's voice singing a few haunting lyrics is still more than enough to send shivers up the spine. The Innocents demonstrates that with the proper atmosphere and a good story, children can be creepy little buggers.

The two creepy kids in question, Flora (Pamela Franklin) and Miles (Martin Stephens), are the niece and nephew of a city gentlemen who can't be bothered with the burden of raising children. Instead, he opts to hire Ms. Giddens (Deborah Kerr), a governess, to supervise the children at his idyllic country estate. However, the longer Ms. Giddens stays in the house, the more she notices that the children's behavior is strange, often mature beyond its years. When she finally learns about the perverse relationship between the previous governess, Ms. Jessel, and Quint, the valet, Ms. Giddens begins to suspect the restless spirits of the deceased haunt both the house and, more importantly, the children.

A combination ghost story and psychological horror, it's never made clear whether the house is haunted, the children possessed or Ms. Giddens simply mad. Through the collaboration of Truman Capote and John Mortimer (the latter of whom is responsible for the additional scenes and dialog), The Innocents is carefully adapted to the screen from the original short story "The Turn of the Screw" by Henry James. By blurring our perception of the children’s ages, of the house's history and even of the authenticity of the film's spectres, the writing lends a sense of unreality and uncertainty to the film and its characters. Miles, reciting poems and dispensing adult wisdom, seems older than his youthful form implies, while Flora seems distracted and distant, more involved in her inner world than her own surroundings. The characterizations of both children, a combination of the expected innocence and these bizarre behaviors, confound our understanding of what is and is not appropriate for their ages, making them seem alien and strange. This ambiguity is further applied to Ms. Giddens. Certain scenes and dialog show her oscillation between a proper governess and a ranting madwoman, a distinction that can change in a matter of moments. When Ms. Giddens, is preparing, in a panic, to leave for London and share her strange tale with the children's uncle, she appears to be at the height of insanity and, when she finally calms and tells the housekeeper she will not be leaving, our relief is almost palpable. Then she speaks, voicing her resolve to stay and protect the children, save them from their possession. Her actions are sane, but her words are not, and suddenly it is impossible to tell the rational from the irrational.

The writing is complemented by wonderful performances by the cast, in particular Deborah Kerr (Ms. Giddens) and Martin Stephens (Miles). Martin Stephens's performance is a perfect example of exactly why children can be so creepy. With his angelic looks and slightly uncoordinated way of moving, outside appearances seem to suggest that Miles is no more sinister than your typical prepubescent boy -- until he opens his mouth. Delivering his lines straightforwardly, Stephens makes it seem as if there was nothing more natural for a child to say, despite the maturity of his words. The poem he recites, which is morbid and adult in nature, is said with no more consideration for its content than a child's flair for drama, making the words sound unnatural. This same sort of juxtaposition between content and presentation is also present in Miles's actions. When Miles kisses his governess, in what is a very intimate and adult kiss, Stephens plays it off as though it were just a simple gesture of affection, with no traces of guilt or discomfit, making the action seem more sinister for its innocent surrounding. Deborah Kerr's performance is no less impressive. Throughout the length of the film, Kerr manages to slowly transition the character of Ms. Giddens from a sweet, naïve young woman as seen in the beginning of the film to the frantic, terrified person we encounter at the end. So convincing is her performance that, by the film's conclusion, Kerr's character seems to have aged, despite little change in her appearance. This progression of decay, which Kerr is responsible for carrying off, is so subtle we are unaware it is even taking place, lending credence to Ms. Giddens as a haunted woman.

While the writing and performances form the framework of the ambiguity which is hallmark of The Innocents, it is the combined work of director Jack Clayton and cinematographer Freddie Francis that really focuses the question of Ms. Giddens's sanity. Rather than clarifying the reality of the haunting, the imaginative use of the camera only confounds. It becomes apparent early on in the film, through the heavy use of point-of-view camera angles, that much of the on-screen experience is seen strictly through the eyes of Ms. Giddens. While this in itself is not unusual, combined with the appearance of Ms. Jessel and Quint's ghostly apparitions, it effectively removes the believability of the viewer's own eyes. Not once in the entire film do we see a single ghost fade away or disappear. Rather, we see the apparition through the eyes of Ms. Giddens, the camera shifts away and, when it returns, the apparition is gone, leaving us wondering if what we're seeing is really there – or if we are simply privy to the blossoming madness of a hysterical governess.

Composer Georges Auric’s hauntingly beautiful musical score compliments this atmosphere of uncertainty. Reminiscent of older, traditional folk music, the ethereal melodies compliment the film, reminding us of old superstitions and times when the spirits of the dead held power over the living. Of particular note is the somber, lilting ballad, “Oh Willow Waly” which is sung by Isla Cameron in a false soprano, mimicking the voice of a child. This tune, which plays during the opening credits, is a reoccurring motif throughout the film – played by a music box, hummed by Flora, or heard eerily in the distance by Ms. Giddens. By using the music to tie together otherwise disparate scenes in the film, minor details are given heightened significance, drawing attention either to the children's strange behavior or Ms. Giddens's growing instability. Further, since the film's soundtrack consists mostly of harmonious, complementary tones, those times the music takes a turn for the dissonant are exceptionally jarring, providing as much of a shock as the visual imagery they accompany.

Ultimately, however, the film is not strictly about ambiguity and the terror of uncertainty. While it is true that we never really learn if the spirits of Quint and Ms. Jessel are haunting the children, the true horror of The Innocents lies not in this ambiguity, but in the decay it highlights: the decay of sanity, the decay of social norms, and the decay of innocence. The imagery of decay is everywhere – the flower petals that fall to the ground or the aging, bug infested statuary in the garden. More disturbing, the children themselves are forces of decay. Damaged by the perverse relationship between Quint and Ms. Jessel, the children have been corrupted, their innocence disturbing and twisted. When Miles turns to Ms. Giddens and calls her a hussy, a dirty old hag, he immediately flees and then breaks into tears, shocked at his owns words, reminding us of the fragility of innocence. Decay, like death, is unavoidable.

Uncertainty and decay, coupled with a very talented production crew, make The Innocents a downright creepy film, the kind that haunts you long after the lights have been turned back on. Not to mention, of course, kids are damn creepy.

In 1974, Year 11 English

In 1974, Year 11 English students (boys' college) asked for THE EXORCIST to be included in curriculum. I had a policy: "Yes, if compared with an extra work of my choice." They responded with intelligence & sensitivity to TURN OF THE SCREW's plot, character and language. Some pursued James' other works. The film's image of a nasty arthropod crawling from the mouth of a marble putto or infant angel is one of the most evocative images of evil that I've ever seen. Georges Auric's score is worthy of any of Les Six.