Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

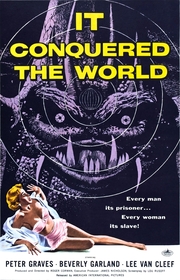

It Conquered the World (1956)

In the 1950s, the Cold War was steaming up and alien invasion movies were making big bucks at the box office. Combining the two was a natural pairing that emerged throughout the decade . One of the more intelligent efforts to come from that era is Roger Corman's It Conquered the World. Written by Corman's friend and frequent collaborator Charles B. Griffith, the film uses its alien antagonist to play on the fear of Communism as a external force bent on brainwashing and depersonalizing humanity, while simultaneously exploring a very human debate about the pros and cons of the "Red Menace." The result is a deeply satisfying, thought-provoking viewing experience.

Dr. Tom Anderson (Lee Van Cleef) and Dr. Paul Nelson (Peter Graves) are scientists and friends who live in the small hamlet of Beachwood. Anderson was once a prominent physicist, but years of naysaying and doomsday prophecies have left him discredited and unemployed. Nelson is a top scientist in the US space program with his entire future ahead of him. When a mysterious malfunction causes Nelson to recall his latest satellite to terra firma, something comes along with it - a Venusian (Paul Blaisdell in an adorably ridiculous monster suit) who has been in communication with Anderson for some time. With Anderson's assistance, the alien puts its plans for domination into effect - first, Beachwood, then the world!

The primary narrative of It Conquered the World works as a sci-fi sublimation of "commie panic." Griffith1 uses Beachwood as a scale-model of America in order to present a worst-case scenario of Communist invasion, substituting in an alien from Venus for comrades from Russia. Like Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers (also a 1956 release), It Conquered the World plays upon a fear of Communism as a form of brainwashing and emotional dissolution. The invading Venusian uses bat-like probes on a handful of key military, law enforcement, and scientific officials. The probe's sting "frees" the victims from their emotions, but also brings them under the alien's complete control. In no time, these instant collaborators send Beachwood into a panic and exile the military to the outskirts of town. They don't need to control everyone, as was the case in Siegel's film, but rather just the right people. The fear and confusion of the townspeople does the rest of the work for them. In many ways, this is a more damning invasion scenario than Body Snatchers, as the whole plot is held together by the actions of a single canny extraterrestrial and his non-controlled human collaborator, Anderson.

How a human like Anderson could betray his own species without coercion or mind control is key to the political themes of the film. Griffith is careful to make Anderson a sympathetic character with believable, if obviously misguided, motivations. "I believe [the Venusian] is here to rescue mankind, not to conquer it as you have naturally concluded," Anderson says to Nelson once he's revealed the existence of the alien to his friend. Anderson, beaten down by "a world of fat heads," has come to see the selfish emotions of others as the reason for his downfall and the eventual downfall of the human race. When the Venusian offers a world without these problems, a world made entirely of logic and cold reason, Anderson jumps at the chance. It's likely he sees the potential new order (read: Communism) as a way to come out from under his own problems. With a zeal that's almost frightening in its naïveté, he sweeps away the moral and philosophical implications of removing the emotions and free will of the world by force.

The cruel irony is that, as Nelson points out late in the film, Anderson's reasons for collaborating with the Venusian are driven by emotion. Despite an astonishing education (he has "every degree imaginable"), he's still an adolescent boy longing for a simpler world, one where the things he wants come without complication. When he tries to explain to his wife, Claire (Beverly Garland), how things will be without emotion, he tells her that she's "every thing I must have as a man" and that his needs will continue unabated even without love. It's clear he's looking forward to a marriage that's more about pleasure than feelings, but he's completely oblivious to the fact that he's just reduced Claire to a sex object (thankfully, Claire points out his error quickly). More importantly, Anderson wants a world where he and his ideas are accepted ("The days when people made fun of me are over"), but peer approval lacks that certain shine when you haven't any emotions to appreciate it.

Standing up for humanity's right to feel is Dr. Paul Nelson, filling the narrative role of the protagonist and the political role of superior American cunning and machismo. On the surface, Nelson's exactly the type of virile man needed to lead the USA to victory over its would-be conquerors. However, he too has his own contradictions and flaws. Despite being a scientist, he occasionally falls prey to the anti-intellectualism that had been on the rise in America since the implications of technological progress were made abundantly clear after the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Walking away from dinner with Anderson, Nelson remarks to his wife, "Tom's a genius... too much so." His solutions to the pressing alien invasion usually involve his fists or a gun, rather than attempting to use his considerable powers of reasoning. Once he's seen the effects of the Venusian's mind-control, he develops an encompassing us-or-them position. This follows its logical if tragic extreme when [SPOILERS] Nelson discovers that his wife (Sally Fraser) has come under alien control. In response , he shoots her. He doesn't make any attempt to find out if there's any way to bring her back or remove the probe. When confronted about his actions, he says, "She wasn't my wife. She was a product of your [Anderson's] work, a member of the society of the new world." Once she had gone over, she was better off dead.

The fact that Nelson and Anderson become enemies speaks more to their similarities than their differences. Both are men of science, dedicated to the advancement of the human race. They only differ in their ideologies. Anderson believes that the human race is flawed, held back by their emotions. Nelson's much more of a humanist; he argues that without emotions, we are diminished shells of ourselves. On any other day, their philosophical difference would be scintillating dinner conversation. Today, however, whoever wins this debate decides the fate of the human race.

It Conquered the World is at its most fascinating when Anderson and Nelson are debating the new world order, not because either is particularly persuasive, but because they both hold so tenaciously to their own dogma. The harder that Nelson grills him, the more Anderson's defenses of the alien become illogical as he attempts to hold onto some hope that he hasn't been duped. When Nelson presents a litany of crimes committed in the name of "their new master," Anderson (after a brief moment of shock beautifully played by Van Cleef) attempts to point out the moments of great human achievement that have followed human atrocity. Nelson naturally counters that this is an alien atrocity and so the comparison is inapplicable. However, Nelson's arguments for humanity are usually just empty jingoism. He attacks Anderson with charged statements like, "Your hand is human, but your mind is enemy." The substance of his arguments is more eloquent but often ignores obvious evidence; his statement that "pure logic works only for the individual, there's no group feeling, no patriotism, no cooperation of any kind" is refuted by the fact that those under the alien's influence have worked quite well as a unit throughout the film. In the end, neither Anderson or Nelson make an argument that would convince the audience, since their own dogged need to be right overrides any chance they had at a reasonable debate.

The rich philosophical and political content in It Conquered the World doesn't prevent issues from cropping up. The unfortunate padding, for instance, is difficult to ignore. Forced to pad the action to a feature-worthy 71-minutes, Corman and editor Charles Gross give us an inordinate amount of footage focused on Nelson going here in a car and there on a bicycle, over to the base and back to Anderon's. In one bit, we watch Nelson get into a jeep, back it up to the edge of the driveway, pull forward, and then back out onto the road and drive away, and for no other reason than doing so fills nearly half-a-minute. The fault here is as much with Griffith as it is with Corman and Gross; had he provided a script with enough action, the needless filler might not be necessary.

By the time It Conquered the World reaches its inevitable conclusion, with Anderson and Nelson working together to fight the common enemy, it's thrilling but not as interesting as when the two were opposing one another. There are plenty of alien invasion movies with anticommunist themes from the 1950s, but so few provide us with human characters as rich as the ones that Charles B. Griffith conjures up here. It may not have Conquered the World, but it certainly stays in the brain.

1. The

film credits the screenplay to Lou Rusoff, but according to Bill

Warren's Keep Watching the Skies, the writing is almost all

Griffith's.

Well done post on this film.

Well done post on this film. Great you explored the analogies to the red panic of the time. Many films were most likely using giant radiactive insects or monsters as a substitute for communism. Not sure how conscious the filmmakers were of all this but it still seems obvious now looking back. I have even noticed sometimes a theological theme in some of Roger Corman's films like The Day the World ended and Teenage Caveman.

I can't remember my post now but I do recall I wrote a little about the scene where the Peter Graves character shoots his wife in the gut rather than have her be one of 'them'. I think it is a pretty shocking scene for a film like this and I didn't expect it.

The filler scenes can be a bit amazing in these films as you said. How many total minutes are filled by similar shots of a space ship hurtling through space with smoky fire emitting from its tail pipe in amny old sci-fi films. I remember the scene too where Peter Graves backed the jeep in and out of the driveway and wondered if there was something I was missing.

Good job

Bill