Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

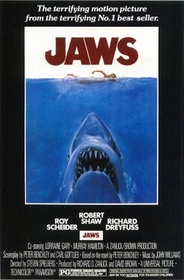

Jaws (1975)

Like most of director Steven Spielberg's works, Jaws straddles more than one genre -- horror/monster film, drama, even sci-fi at a stretch-and like most of them, it is a masterpiece in any genre.

Produced by David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck (who have done such quality, diverse films as Neighbors, Cocoon and Driving Miss Daisy together), the idea for the film first came from Helen Gurley Brown, David's wife and longtime Cosmopolitan editor, after she discovered Peter Benchley's novel. Brown and Zanuck had both worked with Spielberg as producers of his 1974 film, The Sugarland Express, so when he approached them to also work on Jaws, they agreed.

The story, as most of you know by now, is simple on its face, concerning a small New England island, Amity, and its shark troubles during one Summer season. That's it really for the premise, and the deceptive simplicity is one of the reasons that the Jaws sequels have not faired so well as this work of brilliance. Most of the sequels misconceived Jaws as a kind of slasher film, with a shark in place of a masked, voiceless human. (Interestingly, one of the child victims in Jaws is played by an actor named Jeffrey Voorhees -- coincidence?)

There are many alternative ways to see Jaws, from a modernization of Moby Dick (and with that, all the possible readings that Melville's work possesses) to a commentary on the contradictoriness and occasional absurdity of political goals, to an overcoming of deep-seated fears (Brody's fear of the water, Quint's fear of death at sea by sharks, Hooper's fear of relying on more intuitive methods, everyone's fear of the unknown), and then some. These subtexts are a large part of what makes Jaws a masterpiece.

Another primary factor is Spielberg's direction. You could randomly pick almost any scene and point out unusual, often subtle aspects of the direction that make it rise above the norm. I'll discuss just a few.

During the opening scene when the couple from the beach party leave the crowd to go skinny-dipping, Spielberg films only 10 minutes or so before sunset. This is unusual because it is so difficult--there's only time for a take or two before you lose the lighting and would have to wait until the same time the next day, where you'd again only have a few minutes to shoot. Although it's difficult, it makes for incredibly beautiful, almost surreal lighting.

During the first attack scene, we never see the shark. We don't see any blood either. We only see the girl panicking, being carried by something quickly through the water, then going under, not to surface again. This is more suspenseful at first because we don't know what the menace is. But unlike, say, the creators of The Blair Witch Project, Spielberg realizes that to never know the menace would be simply aggravating. So as Jaws progresses, we see more and more of the shark, and it never loses any potential to scare. Rather, it gives the film increasing tension.

The way that we first discover that it was a shark attack is brilliant. Chief Brody is on the phone with the coroner. We can only hear Brody's side of the conversation. At the tensest moment, we see a shot of Brody's typewriter and police report. As the coroner tells him, he types in "Shark Attack" for the suspected cause of death.

Spielberg takes a lot of time for character development, but he doesn't lump it all together at the beginning of the film, like many lesser directors who create a bore-fest for 45 minutes or so then try to develop some suspense. Scenes like Brody's son mocking Brody's expressions at the dinner table, or Quint's speech about why he hunts sharks, are crucial to understanding the motivations of characters, but Spielberg makes sure they come at times where a release of tension is needed.

The cast also deserves credit of course, especially the three principals -- Roy Scheider (Brody), Robert Shaw (Quint) and Richard Dreyfus (Hooper), who all bring depth and believability to their portrayals as well as realize complex interactions with one another.

And of course we're all familiar with the ingenious music that John Williams composed for the film, especially the ostinato that announces the shark, which, like many other aspects of Jaws, has become part of our popular culture. Other production aspects deserve mentions as well, from Bill Butler's superb cinematography to the mechanical shark itself, which, despite the well-known tales of it not working most of the time, still looks menacing.

Jaws is a penetrating drama, a kind of throwback to 1950's monster films, and as I mentioned in my first paragraph, can even be seen as science fiction (just like many of the 1950's monster films). It's not futuristic, but its biological facts are accurate (surely with some thanks to Ron and Valerie Taylor, shark experts who filmed the live Great White sequences) and much of the approach to hunting and killing the "monster" is rooted in science.

Understandably, Jaws has influenced films from Alien to I Know What You Did Last Summer to Deep Blue Sea, whether in the general arc and construction of story, the setting, or more literal takes on a monster at sea tale. Even if this weren't the case, Jaws would still be essential viewing for anyone serious about film.

Trivia:

Robert Shaw wrote the Indianapolis monologue himself.

Sterling Hayden had to turn down the part of Quint due to problems with the IRS.

The mechanical shark was named "Bruce" after Spielberg's lawyer.

Spielberg's dream cast was Robert Redford, Paul Newman, and Steve McQueen.

Jeff Bridges and Timothy Bottoms were considered for the part of Hooper.

Some elements changed between the book and the movie: Hooper's affair with Mrs. Brody (non-existent in the film), the details of Quint's death (drowning in the book).