Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

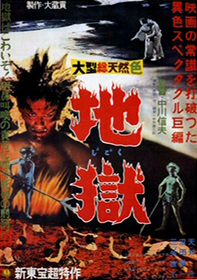

Jigoku (1960)

Hell is other people. The road to Hell is paved with good intentions. Go to Hell. Raise some Hell. Your own personal Hell. Hell is for children. Life is Hell. Hell yeah. Where are we going and why are we in this handbasket?

Nearly every culture has a concept of Hell – a place where the wicked go to suffer for their sins. As an abstract, it's more emotionally evocative than paradise or heaven, and, as such, it informs more of our art, fiction, and conversational idioms. Hell is also a pervasive force in cinema, from F.W. Murnau's inferno in Faust (1926) to Jose Mojica Marins's hallucinatory climax in This Night I'll Possess Your Corpse (1967) to Clive Barker's labyrinth of pain in Hellraiser (1987). In Japan, the seminal depiction of Hell on film is Nobuo Nakagawa's Jigoku. Made for Shintoho Studios in 1960, Nakagawa's treatise on the afterlife is equal parts thoughtful, trippy, and gory as, well, Hell.

Shiro Shimuzu (Shigeru Amachi) is having a rough couple of days. He's an accessory to a hit-and-run accident that took the life of a Yakuza gangster. When he tries to turn himself in, his taxi crashes, killing his fiancee Yukiko (Utako Mitsuya). Oh, and his best friend Tamura (Yoichi Numata) is more like his best fiend – he has a tendency to simply appear out of nowhere and has an uncanny knack for knowing people's greatest sins. Shiro, who feels guilty for everything that happens to the people close to him, receives word that his sick mother has taken a turn for the worse, so he heads out to Tenjoen, the nursing home his father, Gozo, owns. There he meets Sachiko (Mitsuya again), the spitting image of his dead sweetheart. Shiro doesn't have enough time to wrap his head around the coincidence, though, because Tamura quickly shows up and events start to get... heated.

Jigoku is divided into two sections in terms of general pacing and visual style. The first section, which we'll call The Road to Hell, comprises the first two-thirds of the film and is covered in the synopsis above. The last part of the film we'll call Hell Itself and no synopsis can adequately cover it. It's tempting to say that the Road to Hell is mere prologue to the real “meat” of the film in Hell Itself, but for reasons we'll explore later, such notions do Jigoku ill service.

The Road to Hell

The primary purpose of the Road to Hell section is to demonstrate why each of the characters is a likely candidate for Hell. The first-time viewer who is unaware of what lies ahead in the Hell Itself section may find this a little confusing, as this first part of Jigoku unfolds like an extremely cynical drama with only the barest hint of the supernatural, although there's more here than meets the eye.

One can't be blamed for being lulled into taking the Road to Hell section at face value, as Nobuo Nakagawa films the whole thing in an almost excessively straightforward and understated manner, if such a thing is possible. Colors here are muted and tend towards brown, subtly emphasizing the mundanity of the real world (although the color red does get special emphasis, a means of foreshadowing the inferno still to come). Nakagawa also favors shooting in shadow, with the characters barely illuminated, giving the picture a heavy, almost artsy feel. He's also careful to connect his characters strongly to their environment, such as the foot-level shot where Shiro walks beside the railroad tracks, his shoes audibly crunching the gravel underneath.

While the direction may be understated, the writing is not. Most of the characters we meet are waist-deep in sin, most of it particularly heinous. Shiro's father carries on with a mistress while his wife lies dying in the next room; he also neglects the needs of the residents at his nursing home (ironically, Tenjoen means “Heavenly Garden”). Tenjoen's staff doctor is too lazy to bother with getting second opinions, even when he knows his paltry medical skill is probably killing more patients than it saves. A corrupt cop takes bribes and threatens to arrest Sachiko's father unless the girl marries him. These are not nice people and they are, for the most part, the only representations of humanity we get, which creates a rather bleak portrait of the world.

In the midst of all of this terribleness is poor Shiro, not as bad as any of them, but not particularly good either. Still, he's not guilty of much more than a little pre-marital sex. His worst sin is passivity. He heaps guilt upon himself for the hit-and-run (even though he was not the driver), but he never actually goes through with his plans to turn himself in. The fatal crash that takes Yukiko is a factor in that decision, but he never properly deals with that tragedy, either. Instead, he tries to escape his problems by leaving the city. Ostensibly he does this as a good son, but Shiro never fully engages with his mother's plight, or anything, for that matter. When his father's mistress Kinuko (Akiko Yamashita) comes on to him, he neither encourages nor discourages her advances. He's not living so much as waiting, waiting for his undeserved karmic punishment to begin. And when it does, it does so in earnest...

Hell Itself

With roughly forty minutes to go, Jigoku takes a sharp turn into the esoteric, changing its cinematography, tone, and most importantly, setting. After a slambang party which ends with everyone dying, we're transported to the banks of the curious-looking River Sanzu. This waterway has corollaries in other mythologies – the Greek called it Styx, the Hindus Ras?. Whatever the name, the purpose remains – the river is the threshold of the underworld. Yes sir, we've entered the Hell Itself section and the movie gets really interesting from here. Each of the horrible, no-good, very-bad people we've met throughout Jigoku receive all the punishments they deserve (and more) in as much gory detail as Nakagawa can muster.

Jigoku's version of Hell is roughly based on the lowest state of existence in Buddhism, the mythology of which is fascinating. Those who have sinned in life will, in death, go to Hell to atone. Depending on the kind of crime they committed, they'll be sent to one of several different kinds of Hell (the exact number of which numbers somewhere between 8 and 144), all of which are presided over by King Enma, a bearded giant with red skin. One Hell, for “sexual misconduct,” crushes the sinner between two iron mountains. Another slices thieves into neat pieces. However, unlike in other cultures, the Buddhist Hell is not eternal and once atonement is complete, the redeemed sinner can move on to higher states of existence. 1

Would that such escape seemed possible in Jigoku. While a path of redemption is presented for Shiro (he is the hero, after all), most of Hell's other denizens seem to be there for the very, very long haul. More than just a pit of fire and brimstone, Nakagawa's Hell is a grim, oppressive realm of doom. Here, sinners get their teeth bashed in, feet impaled, bodies boiled, skin flayed, eyes gouged out, and their hands chopped off, only to see themselves restored for the next round of suffering.

While Nakagawa's Hell retains many of the characteristics of the Buddhist Hell – King Enma still passes judgment and punishments are still tailored to the crimes – he eschews the separation of hells. Everyone heads to the same basic place, a featureless world where the only landmarks are instruments of torment and the sky is an infinite black void. According to screenwriter Ichirô Miyagawa, the utilitarian approach to Hell was a result of budget concerns more than artistic vision – Shintoho Studio was close to going under, and there wasn't much money for anything complex.2 Whatever the reason for the approach, Nakagawa takes full advantage of it, even using the blank canvas to produce some visually stunning punishments, like the mob of people forced to run in circles endlessly, pushing and shoving against each other in their desperate bid to get to nowhere.

Every technique that Nakagawa employs in the Road to Hell is reversed here. He proves himself to be, in many ways, the Japanese Mario Bava3, using color and composition in creative ways to create a sumptuously skewed reality. While darkness still surrounds everything, the characters themselves are always illuminated in eerie greens, blues, and reds. Some of Nakagawa's visuals seem like paintings come to life, particularly the grotesque scene where a procession of the damned wades, single-file, into a boiling green river made of their own pus and excrement, while King Enma looks on. Other times, Nakagawa chooses a more dynamic approach, using distorting lenses, tilted angles, and extreme closeups to displace the spacial relationships of the objects in frame, pushing them into the face of the viewer. Nakagawa uses this particular technique mostly when he's exhibiting the worst tortures of Hell, so that we are overwhelmed as surely as the characters are.

From a lesser director, this last forty minutes might the only worthwhile thing in the film. However, there's one more trick up Jigoku's sleeve, one that doesn't become apparent unless the film is appreciated as a whole. There's a major revelation that creeps up on you, hours, days, or even weeks later...

Truthfully, I haven't been playing entirely fair by sectioning off Jigoku as I did. The labels “The Road to Hell” and “Hell Itself” aren’t really accurate. While there is a difference between the first two-thirds of Jigoku and the last third in terms of their methods, they share the same madness. Hell is never a destination in the film, it is the ever-present reality. From the first frame to the final fade, every moment of Jigoku's story takes place in Hell.

It's All Hell

The heck, you say? Let's take a look at the evidence, which borders on overwhelming. First of all, when we first see Shiro – moments before he is startled awake in his theology class on the nature of Hell -- he's standing on the banks of the river in Hell, screaming, right before he falls into a burning ring of fire.4 It could be a flash-forward, a teaser for a future scene, except that the moment by the river bank is never repeated. Moving even further back in the film, we come to the bandaged figures floating in a pool of water, as a grave narrator describes the purpose of Hell. Who are these men? This bit, over quickly and never repeated, could be unrelated to the rest of Jigoku, like the crazy parade of women and noise that accompanies the opening credits, but that doesn't parse, given the narration that seems to obliquely tie the bandaged men with the narrative of Hell. I believe this is just one of the many punishments that Shiro endured before the film even began.

If the first part of Jigoku takes place not in the “real world”, but in another area of Hell, it would certainly explain the unrelentingly dark tone. Like an evil version of Murphy's Law, anything that can go wrong, will go wrong – and then it will get worse. This is especially true during the anniversary celebration at Heavenly Garden, where people start dropping like flies. Many of these deaths are silly; for instance, Yoko (the late Yakuza thug's girlfriend) breaks a heel and topples over the edge of a rope bridge. Not long after, the entire population of the home and all of Gozo's cronies are also dead or dying. In a normal world, this kind of mass death doesn't generally happen without a political or religious philosophy to drive it. However, if this is part of the punishment of the characters (or perhaps just Shiro), then we start to see how maybe all that terrible coincidence is just King Enma or Tamura pulling the strings.

Why the additional dramatics? And what sort of play is this anyway? To answer this, I point to Mario Bava's Lisa and the Devil. While that film, like Jigoku, has multiple possible interpretations, my favorite has always been that the Devil (Telly Savalas) is putting on a puppet show to remind Lisa (Elke Sommer) of her crimes in a past life. The events that occur in the movie are not exactly the same as the heinous ones to which the Devil's puppets allude, but they are close enough to serve the Devil's purpose, for – as I said in my Lisa review -- “what soul can go to Hell without knowing its sin?” Applying this interpretation to the first two-thirds of Jigoku isn't difficult – the result is a quick-pace, compressed-for-time version of the characters' real-world transgressions, spaced together closely enough to fully illustrate the awful nature of each act. It also legitimizes some of the “just-a-little-too-weird-for-reality” moments I talked about earlier.

I say “some” because the character of Tamura is problematic, regardless of how the film is interpreted. In the first section of the film, Tamura acts as a curious mix of moral judge and agent of chaos. He knows the sins of even the most respectable members of Shiro's social circle and delights in pointing them out. Yet he is as guilty as anyone; he's the one driving the car that runs down the Yakuza thug and, when Shiro threatens to go to the police, appears to engineer the car crash that kills Yukiko. There is something obviously supernatural about Tamura -- he has a tendency to pop up in places where there wasn't anybody seconds ago (Nakagawa highlights the sudden appearances with the sounds of trains and planes to suggest that Tamura is his own method of transportation). Tamura frequently appears to be lit from underneath, giving him an otherworldly appearance. If he's a demon, though, why does he receive the really awful torments in the second part of the film and why does he seem surprised by this? And if he's not part of Hell's architecture, where did he come from? It's not like the Buddhist philosophies informing Jigoku really allow for an agent to whom Tamura could've sold his soul for power in Hell. And even if he did, why does he call out for Shiro – poor, powerless Shiro – to save him when the blood starts to flow?

Perhaps it is because there's a deeper connection between Tamura and Shiro than tormenter and tormented. In fact, Tamura often comes across as Shiro's doppelganger, a la Edgar Allan Poe's short story “William Wilson.” The comparison is imprecise, of course, as Tamura doesn't look much like Shiro, but the way the two characters exist in perfect opposition is eerie. Tamura is everything that Shiro is not – extroverted, confident, powerful, judgmental, and utterly without remorse. Yet Tamura never publicly attacks Shiro's moral character as he does with everyone else. When he wants to hurt Shiro, Tamura never does it directly – he goes for the ones Shiro loves, instead. Tamura's interest in Shiro's well-being, though, stops when they get to the pain-and-suffering part of Hell. There Tamura's cool facade falls away, and he becomes almost psychotically agitated in his attempts to convince Shiro that they both deserve to burn. Tamura's shift in attitude and demeanor suggests that he has a vested interest in Shiro remaining as one of the damned, as if his very existence depends on it.

There's one really good explanation for the Shiro/Tamura relationship as I see it, but it requires a little dive into Buddhist theory, so bear with me. The fourth-century Buddhist philosopher Vasubandha once attempted to reconcile one of the major contradictions of a karmic Hell. The very nature of the karmic cycle is such that people are “born into” a particular state of existence based on their actions in a past life. Hell is the lowest of these states, a state of perpetual punishment for the wicked; the only entry is through the commission of heinous sin in a previous life. Buddhist lore also states that Hell has guards that apply these tortures. If to be in Hell is to be punished, though, how do the guards escape this fate? Vasubandha argued that there really weren't any guards at all – that they were the projections of the suffering souls.5 In Vasubandha's argument they are group hallucinations, formed by the communal understanding of Hell held by the suffering masses. However, taking the argument further, wouldn't it be possible for a single person with a great enough mental burden – someone like Shiro -- to create their own private tormenter? Following along those lines, wouldn't the newly created being, formed to punish the guilt of just one person, be intrinsically connected to that person? They might steal the darkest natures of their creator, in order to act against them with extreme malice; in doing so, they might even take on their creator's sins. Mind you, this is only one of many imperfect explanations. For all I know, Tamura might have expunged his “lesser qualities” into the form of Shiro in an attempt to create the perfect patsy for his crimes in life.

Ultimately, the point to Jigoku is not to find the correct interpretation. You may, in fact, disregard my entire analysis and decide that the last forty minutes is a dream Shiro has in his dying moments. The point of Jigoku is that, in being a film so open to interpretation, it has a certain timelessness, as critics and film buffs go back and forth on what all of it really means – or if, indeed, it means anything at all. These are the films that I find the most rewarding and I look forward to rethinking Jigoku for many years to come.

1 McCormick, Rev. Ryuei Michael. "Who's Who on the Gohonzon?: The Vedic Cosmology." Nichiren's Coffeehouse and Gohonzon Gallery. Published 2002. Retrieved 23 October 2008. <http://nichirenscoffeehouse.net/ShuteiMandala/vedic.html>

2 "Building the Inferno." Jigoku. DVD. 1960. Criterion Collection, 2006.

3 Technically, Nakagawa was already directing for a year before Mario Bava even started as a cinematographer (and twenty years before Bava took up the director's chair himself), so it might be more accurate to call Bava the Italian Nobuo Nakagawa.

4 With apologies to Johnny Cash.

5 Lusthaus, Dan. "Vasubandhu." Yogacara Buddhism Research Association. Publication Date Unknown. Retrieved 23 October 2008. <http://www.acmuller.net/yogacara/thinkers/vasubandhu-bio-asc.htm>

Trivia:

Money was so tight that, for the scene where many of the characters had to appear buried up to their necks, the actors had to help dig their own pits.