Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

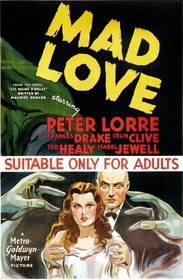

Mad Love (1935)

Mad Love is a curiosity of 1930s Hollywood horror. Rather than a tale of a monster on the loose or of a mad scientist with a lust for glory, Mad Love is about a man at loose ends and a mad man who happens to be a scientist. It isn't that some of the movie's themes are sexual; the film dives head-first into the sea of sexual desire and the destruction that occurs when it is sublimated and perverted.

Actress Yvonne (Frances Drake) is retiring from the simulated torture and bondage of Paris's Theatre des Horreurs (a take on the Theatre du Grand Guignol), in order to be with her husband, concert pianist Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive). Yvonne's departure from the stage greatly disturbs her biggest fan, the renowned surgeon Dr. Gogol (Peter Lorre), who buys the wax figurine of Yvonne from the theater lobby as a shrine to his favorite star's beauty. When Orlac's hands are damaged beyond repair in a train wreck, Gogol gives him the hands of the guillotined knife murderer Rollo. Soon Orlac is tossing any convenient knife he can find, a problem that Gogol encourages in order to conquer Yvonne's heart through his own twisted means. Yvonne rejects him utterly, however, sending the good doctor into the warm and loving embrace of madness.

Although Mad Love is ostensibly an adaptation of Maurice Renard's 1920 novel Les Mains d'Orlac, director Karl Freund and scenarist Guy Endore have relegated the tragic story of a pianist given the hands of a killer to a subplot. The main focus here is on a new character, Dr. Gogol, who seems custom tailored for Lorre's Hollywood debut. Indeed, while the character existed in drafts of the screenplay prior to casting, the part was reworked once Lorre had the part (one note in the final script calls upon Lorre to give "his M look"1). This decision to shift the focus of the source material away from Orlac and onto this new character works for the film and adds a psychosexual bent that is immensely satisfying.

Dr. Gogol is portrayed as a brilliant surgeon and a petulant child simultaneously, with Lorre's baby face and shaved bald pate adding visual dimension to this characterization. Although Gogol is respectful and professional in matters of medicine, in matters of life he is uncertain and occasionally behaves inappropriately (at one point he grabs Yvonne and kisses her deeply in front of a crowd of people). There are suggestions throughout the film that he enjoys watching others suffer more than he should. Gogol watches Yvonne's performance at the Theatre des Horreurs from his private box, half in shadow. As Yvonne's flesh is "seared" by the hot irons of her "torturer", Gogol's eyes close and he breathes in deeply; the cruelty to Yvonne's person sends him into sexual ecstasy. Once Yvonne spurns the doctor's advances, his lust for her takes on a dimension beyond mere sex . She is no longer his Madonna Whore fantasy, the object of his creepy if petulant infatuation. Rather, she becomes an object that he must possess simply because he's been told without exception that he cannot.

No line sums Gogol's monomaniacal pursuit of Yvonne better than his histrionic exclamation "I, a poor peasant, have conquered science! Why can't I conquer love?" The words sound silly read aloud and Lorre's delivery of them seems to break the bounds of the scene and occupy a strange netherspace all of its own. I believe this is the point. We know that conquering is antithetical to loving, but Gogol's perspective is that of the surgeon, the scientist. In the world of science, things are put together a certain way and despite the multitude of variations, a basic template and pattern is maintained. There is no boundary he cannot breach given infinite time and infinite self-discipline. That his work is on human bodies makes his mania complete -- human beings are parts that can be fit together on the operating table. To his mind, Yvonne's heart should be no different and he should be able to fix it so that it does what he wants. If he cannot do that, then he'll do the next best thing and remove the aberration from existence like a cancer.

As Gogol's perverse obsession increases to a point beyond sexuality, cultured Stephen Orlac watches his own virility decline. As Yvonne says to a doctor who wants to amputate the pianist's hands, "Doctor, you don't understand. His hands are his life!" Orlac's entire livelihood is the piano. The act of amputation is tantamount to castration. That Gogol, a man who lusts after Yvonne, is the one who removes the hands adds a measure of insult, but the deepest cut occurs when Gogol then replaces those hands with a crueler, alien pair. The new hands, scarred and grotesque, could never caress the ivory piano keys the way that Orlac's natural talent demands. He is able to bang out out only the simplest of melodies, and even those attempts are fraught with embarrassing mistakes. Soon, the new hands, frustrating in their inability to recreate their owner's glory days, are throwing knives. In response to his emasculation, Orlac has subconsciously turned to violence for release of his tensions (while we are meant to accept that the hands kill on their own, they don't begin to take action until Orlac gives in to despair and anger). It is somewhat unfortunate that producing studio MGM dictated a traditional ending, where husband saves wife from the clutches of madman. In the waning moments of the film, the new hands and their frightening knife-throwing abilities are shown in a heroic light. Despite this, given Stephen's despair at his reduced circumstances, there's probably very little happiness awaiting either he or Yvonne after the film ends.

Much of director Karl Freund's visual style, with the sharp angles of the set design, the chiaroscuro lighting, and the impressive depth of field, seems lifted from the exaggerated worlds of German expressionist silent cinema. This isn't surprising; Freund worked as cinematographer on several of those films (including The Golem and Metropolis), and Mad Love acts as a continuation of that work. He paints a world lost in the depth of shadow, where a man's sexual expression can become ill-defined or distorted. One of the most impressively directed sequences is a confrontation between Orlac and Gogol, disguised as Rollo, the executed hand donor. In the small room where they meet, the two men are surrounded by a gloom that threatens to consume them. The scene ends with the outrageous visual of a maniacal Gogol revealing his neck brace (ostensibly to keep the guillotined "Rollo" from losing his head). Gogol's pallid face, lit from below, seems to create its own disturbing illumination, as if Gogol's desire to own Yvonne and destroy her husband has finally allowed him to express his true madness with utter clarity. Conversely, Orlac, in his flight from the demented figure, runs into the night and back to his own repression.

Karl Freund's direction and the masterful script combine to form a black pearl of horror genius. In Mad Love, passion is everything. Those who carry it to extremes lose their sanity and those who sublimate it don't fare much better. Whether or not you choose to take such a theme at face value, Mad Love's exploration of it should not be missed.

1 Mank, Gregory William. Hollywood Cauldron. McFarland & Company Inc., 1994. Pages 126, 129.

Fantastic. My favorite 30s

Fantastic. My favorite 30s horror film, and a lovely write up. Thanks!