Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

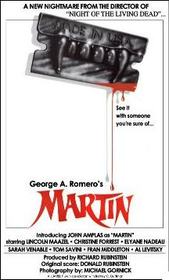

Martin (1977)

Horror fans like vampires. It's a pretty simple concept, really, and one that you'd be hard pressed to refute. Over the years, they have developed a mythology both complex (how many ways can you kill a vampire?) and ridiculous (garlic anybody?), but still surprisingly consistent. However, in 1977, director George A. Romero changed this pattern with the release of Martin. Romero demonstrates, without a doubt, that the terror of vampirism is not in the myth. According to Romero, there is no magic, and that reality is far more terrifying than any creature of the night.

Martin is a film about vampires, but not in the conventional sense. You'll find no fair maidens in distress, no darkly clad shadowy figures, nor any Gothic castles. Instead, you'll find Martin (John Amplas), a troubled youth staying with his elderly cousin, Cuda (Lincoln Maazel) in an impoverished Pennsylvania suburb. There's one small catch though – Martin is one of the family's “shame,” a vampire. Only, Martin is the kind of vampire who uses drugs to subdue his victims, walks in the light of day, and cares little about whether there's a crucifix in the room or not. Martin's behavior, coupled with the complete lack of mysticism in the film, begs the question: Are there any vampires here at all, or are we simply seeing the twisted product of mental illness and family superstition? And, for that matter, does it really matter?

Martin's success as a film can be attributed almost entirely to Romero's direction and writing. While the performances in the film may lack luster, the brilliant shot composition overshadows their mediocrity. The direction in Martin is about harshness, about reality. Much like Romero’s infamous Dead Series, Martin is about stripping the magic from the myth. The camera focuses on the evidence of poverty and the ugliness of the people populating the setting. This mundanity of life that is captured from shot to shot is just as important as the film's plot. While it may seem that this is little point on focusing on dogs fighting for scraps in the street or the image of old cars being converted to scrap metal, they are vitally important to setting the tone, essentially defining the world in which Martin lives – or unlives as the case may be. There is nothing fancy about the direction; the colors and the lighting are harsh and garish, stripping away any hint of romance that might have existed and special effects do not go much beyond flesh wounds and fake blood. Romero's vampire, apparently, does not need such frivolity to terrify.

The only time in the entire film when the direction changes tones is during Martin's fantasy/flashback scenes. These scenes, filmed in black and white, are highly romanticized, a kind of homage to the mythical vampire. Rather than modern Martin, with grungy clothes and mussed up hair, we are privy to the remembered, fantastical Martin, who is dashing and charming and always answering the calls of a beautiful woman. The difference between Martin's fantasy victims and his real-life victims is striking and poignant. Martin's first victim of the film, whom we meet in the first five minutes, is an unremarkable, average looking woman exiting the bathroom to the sound of the toilet flushing behind her. Also, rather than the blushing, compliant maid of Martin's fantasy flashbacks, this woman is anything but willing. She screams, and struggles, even going so far as to leave a small cut on Martin's forehead before the drugs finally take effect and she is subdued. It is unclear whether these sequences, which are so very different from the reality of the film, are embellished memories of an 87-year old vampire or the fantastical delusions of a sick young man.

This ambiguity is one of the most compelling aspects of Martin. Despite being a film “about vampires”, there is no direct evidence one way or another regarding Martin's actual undead status. He is impervious to sunlight, to garlic, and to religious icons. He doesn't have the panache of your typical Hollywood vampire, nor does he possess powers of sexual magnetism or hypnosis. He uses hypodermic needles and drugs to subdue his victims and then slits their wrists with razors to drink their blood. And yet, despite the obvious evidence to the contrary, we cling to the idea that Martin is a vampire, that he has to be. The black and white flashbacks must be memories, not delusions. We hold tight to the casual way Martin states, simply, that he's 84 years old without blinking an eye. We point to the image of Martin, huddled under the bridge, shaking from what can only be described as “blood withdrawals” and say to ourselves, “See, he really is a vampire.” And yet the hard proof, one way or another, is elusive. Or is it?

Romero has stated bluntly that, according to his design, Martin is not a vampire and that all evidence in the film points to a lack of the mystical, to simple mental illness and neuroses. So why is it so hard for us, as an audience, to accept that Martin is just a deranged man? Romero, in writing the film, knew the answer far too well – human beings are far more terrifying than monsters could ever be. So long as Martin is a vampire, he is an other, something foreign and alien and removed from the human experience. But, if Martin isn't a vampire, if he's just a human being like any one of us, it forces us to admit the possibility of violence and horror in each individual. These aren't acts of violence by a monster; they are acts of violence by a person, just like you or me. Familiarity is horrifying. Romero brilliantly accentuates this familiarity by highlighting the fact that Martin, as a person, can be very normal. He runs errands for his uncle's store, goes to church, and even plays with small children in the parking lot. And yet, despite this normality he stalks and murders women, drinking their blood.

Martin then, is not a film about vampires. It is a film about people, about families, about relationships and sexuality and reality. One of the most striking thematic elements of Martin is the sexuality that permeates most aspects of the film. Martin initially can only engage in sexual intercourse with a drugged, unconscious woman. However, with the help of lonely housewife Ms. Santini, Martin overcomes this personal obstacle, entering into his first consensual, adult relationship. While this may seem to be a profound moment of awakening for Martin, a turning point of character, it occurs with little fanfare or commentary. Rather, aside from Martin's comment about how he enjoys “the sexy stuff without the blood”, the sexuality of the film is simply another aspect of life, another way in which Martin is both disturbed and, with the help of Ms. Santini, frighteningly normal.

What is less normal, however, is Martin's family. In particular, Grandfather Cuda is a strange relic from the past, continuing to survive in the modern world, possibly on ignorance alone. Codgery and superstitious, Cuda reaffirms Martin's belief in his own vampirism, calling him Nosferatu and hanging garlic on the doors. He even goes so far as to bring in the community priest, seeking someone to exorcise the devil from Martin's soul, and constantly dismissing his granddaughter Christina's assertions that Martin is suffering from a mental illness. He has hundreds of years of Old World tradition and family history on which to found his belief, and no amount of modern ideology will sway him. What is more interesting, however, is that given the choice between Cuda's superstition and the forward thinking of Cuda's granddaughter, Martin always chooses to believe the former, never once doubting that he is a vampire. While Martin has disposed of much of the magic, this one superstition, thanks to the unwavering insistence of his family, remains the core of his identity.

Martin, while being a film about vampires, does not actually contain any such mystical creatures, magical powers, or even divine influence. Rather, Martin is the story of a disturbed young man, whose evil lurks simply in his humanity. This human quality makes Martin one of the most amiable, yet terrifying monsters of Romero's career, and Martin, one of his greatest films.

I just saw Martin and I must

I just saw Martin and I must say I tend to swing the other way on this subject. Martin freely admits the label of being a vampire is not true, he just has a sickness, a genetic anomily that keeps him youthful longer then any human should, plus that pesky desire for human blood. Romero put some things in the film that he may, or may not remember that make it easy to assume this. Cuda freely asks his neice to investigate the old photo albums of Martin, and specifically names and numbers those still alive with this disorder. We never get to see the evidence, if we had a judgement could be made. Martin freely acknowledges this collaborating the reality and not just inividual head trips as these tend to contradict each other in the truly deranged, deluded mind. Cuda states Martin came to this country when he was thirty two, again specifics. Some of Cuda's superstitions about this condition doesn't hold water to the reality, but the basics of Martin condition seem plausible. The flashback scenes based on this point of view are just that flashblacks. Nothing in them convinces me they are fantasy. Even the way he took blood from the young girl is the same, except now, as he says, "he has needles". Nothing in these scenes looks like any particular vampire movie I've ever seen, I see them as memories before coming to America at thirty two. Martin is grounded and frustrated as he ages but doesnt change. The one thing I don't understand is why he hasn't accumulated wealth, and wisdom, and haven't you heard of blood banks Martin? I mean the guys so concerned with causing harm and pain but I'll tell you what it's still a brutal process waiting for those drugs to kick in before snack time. Thats my take any how. Loved it nonetheless.

Brilliant post on my all-time

Brilliant post on my all-time favorite vampire film. As a teen, I fully identified with the feelings of isolation and overbearing authority Martin feels in the film, despite the fact that he himself is far removed from a teenager, and I consider Martin to be Romero's crowning achievement behind Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead. Most modern, younger audiences will have no idea what to expect or how to appreciate this film, which is why it is a bonafide cult classic. It's no coincidence that my Facebook avatar is a razor blade with vampire teeth, nor that the only tattoo I ever got was the very same image. The film just touched me on so many levels.