Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

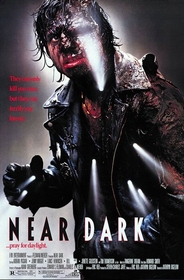

Near Dark (1987)

Since Near Dark's release in 1987, the lore surrounding this innovative vampire Western has evolved impressively. Many cinephiles, including horror fans and their brethren from other camps, consider Near Dark an underground classic. Nothing I can write here in this review can enhance or undermine its legendary status. But as I watched this film for the first time, I must admit I'm not even sure I liked it. But I was sure I was viewing something profoundly unique. That is generally a very good sign, and about 10 minutes into the film, I knew I was in the presence of a very talented director.

In his introduction to The Great Movies, Roger Ebert writes, "We live in a box of space and time. Movies are windows in its walls. They allow us to enter other minds…by seeing the world as another person sees it." If Ebert is correct, which is often a safer bet than not, Kathryn Bigelow has constructed quite a window. Known for her more modestly successful mainstream films such as Blue Steel (1990) starring Jamie Lee Curtis; Strange Days (1995) starring Ralph Fiennes, Angela Bassett, and Tom Sizemore; The Weight of Water (2000) with Sean Penn, Elizabeth Hurley, and Sarah Polley; and K-19: The Widowmaker (2002) with Liam Neeson and Harrison Ford, Bigelow is clearly a player in Hollywood. She married (1989) and divorced (1991) director heavyweight James Cameron, and her background in painting and degree from Columbia's Film School suggest a mind clearly entrenched in aesthetics. Make no mistake about it: the 53-year-old Bigelow is a fine example of an auteur at work, and her fingerprints are all over Near Dark, her most critically acclaimed film.

The film begins with young and handsome redneck Caleb, played by Adrian Pasdar, exiting a bar. He notices Mae, played by Jenny Wright, who is seductively licking ice cream up the street. In a noirish downward spiral, Caleb is immediately mesmerized by her eccentric beauty. He vows to drive her home (perhaps in more ways than one!) and makes several passes at her, but when she finally succumbs, he bites off more than he can chew (or, rather, Mae does!). Slowly realizing he has been transformed, Caleb returns home only to have the sunlight rudely awaken him. He is rescued by a Winnebago full of Mae's cronies, a surreal cast of vampire outlaws led by the scarred, commanding Jesse, played by Lance Henriksen (known to say this was his favorite film), and the demonic Severen, played by Bill Paxton. Caleb travels with this unusual gang, partly due to his attraction to Mae, but partly due also to his new physical state. Caleb struggles with his new vampire role, and he cannot muster the ghoulish strength to kill nor assume the mandate that survival is now predicated on murder.

One of the trademarks of great film or television is their ability to breathe new life into worn out genres. Blade Runner did so with film noir; the HBO series The Sopranos did so with mafia films. Likewise, Bigelow does exactly this with the vampire flick. The old conventions of garlic, crucifixes, stakes in the heart, and reflectionless mirror shots are gone. Nowhere in the film is the word "vampire" even mentioned. What emerges is a new band of vampires dressing in leather, driving in a Winnebago, and functioning like a quasi-family for outcasts. Basically, think The Lost Boys reading Nietzsche and on LSD. These are vampires with an ethical compass, even if the glass covering that compass is shattered. What Bigelow takes great pride in is playing with our assumptions. With the leather, one would expect motorcycles, not a Winnebago. With their murderous desires, one would expect bloodbaths (although there is one in a bar that has launched many replicas), not contemplative scenes full of existential angst and ethical paradoxes. With their alternative lifestyle, one would expect greedy, renegade egos, not a family that sticks together along strict disciplinary guidelines. With their roles as creatures traditionally portrayed as romantic figures, one would expect good looking teenagers or 20-somethings, not an awkward band of ghouls including a heavily scarred Jesse and his aging girlfriend, or the dirty, greasy Severen, or the adolescent and nerdy pudge named Homer. And with their chronological restrictions, one would expect discipline, not a bunch of pot-smoking party hounds that revel on the edges of their own mortality.

And perhaps nowhere does Bigelow play this untraditional portrayal of vampires better than in the role of Caleb, who throughout the film wavers from enjoying his new role to utterly despising it. Caleb does this with skill. He constantly pulls at both Jenny's and our emotions. At certain points, he evokes apathy and contempt because he appears wimpish; he cannot do what we have been programmed to expect him to do: bite and kill another victim for blood nourishment. At other times, he evokes great empathy because he, unlike decades of vampires who came before him, truly agonizes over the destiny thrown upon him. Caleb also wants to belong, as we all do, and when the pack finally accepts him, the smile on his face is worth a thousand words. Finally, he's in, albeit temporarily. And yet we switch once more when we recall that it was Caleb's libido that placed him in this mess. Bigelow paints a very complex picture of a character pulled in contradictory ethical directions.

Near Dark also breathes new life into the Hollywood Western. Although there are a few memorable panoramic shots of the horizon and dry scenery of the American Midwest, what is striking about this film is its use of suburban footage. There are several scenes inside and directly outside bars and extended footage inside the Winnebago, a hotel room, and other suburban lots full of telephone wires, paved roads, neon signs, streetlights, and industrial warehouses. This is the West, but it's not the West of John Wayne or Gary Cooper. Bigelow paints a provocative picture of the new American West, one where clubs have replaced saloons, cars have replaced cows, and Winnebagos have replaced camps. But what remains is the spirit: the outlaw mentality governed by a hungry capitalistic drive that will consume everything in its path. These vampires are no different than those cowboys from the 1940s and 50s; they want blood while the latter wanted land or cattle.

Shot in Oklahoma, the film does still provide some staples of the Western genre. An excellently choreographed shootout occurs, and the scenes of light passing through the bullet holes reminds one of the final scenes in the Coen Brothers' Blood Simple. However, in Near Dark, they add another ominous layer of danger because they represent the vampires' greatest enemy: sunlight. We do have renegades on the run from the law, and we do still have boot and Levis-wearing ranchers and mean looking bikers. The film is also shot in an oil-drilling town complete with giant derricks to remind us that the land is brimming with potential.

The film also contains some unique twists on the traditional femme fatale role in film noir. Traditionally, the black widows are the aggressors, whether overtly or passively. But in Near Dark, Mae clearly is a passive observer and barely succumbs to Caleb's lascivious desires. He is the aggressor, and she does much to warn him about moving any further. Like a femme fatale, her sexuality does spark his demise, but unlike most femme fatales, she persistently sympathizes with and helps him. They are both stuck in a noirish trap, in this case vampirism, and neither is particularly happy about it. They both go through the motions and do the best they can to find romance in adverse circumstances. And unlike most noir male protagonists who usually fail in the end, Caleb does find redemption. Bigelow alters yet another genre to her own aesthetic ends.

Finally, Bigelow's patience as a director is extraordinary. There are many continuous shots without edits, and her patience reminds one that they must look, truly look, at what is on the screen to make sense of what they are witnessing, similar to the way one looks at all visual arts. It is no coincidence that she has an extensive background in painting. More directors should do this because it forces contemplation and engages the viewer in very lasting ways.

And if you haven't decided to see this film yet, see it for one reason only: the bar scene. Clearly one of the best, most daring sequences in horror film history. Just remember: Bill Paxton is really not a vampire.