Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

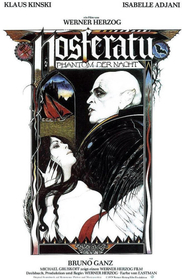

Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (1979)

Nosferatu, F.W. Murnau's 1922 adaptation of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, may be the finest of all vampire films; it's certainly one of the best horror films ever made. To even contemplate a remake of such a highly-regarded masterpiece would be thought of as pure folly. Writer/director Werner Herzog, never one to care what others think, mounted just such a remake in 1979. Filmed simultaneously in German and English, Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (American title: Nosferatu the Vampyre) is Herzog's endeavor – not always a successful one -- to recreate and reinterpret Murnau's film, hewing closely to the original's plot and visuals while adding color, sound, and a more complex reading of the central vampire.

Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz, Wings of Desire) travels from Wismar, Germany to Castle Dracula in Transylvania to finalize a real estate deal with the reclusive Count (Klaus Kinski, Aguirre: The Wrath of God). At first, Harker's host seems like a pathetic, ugly man, but it soon becomes apparent that Dracula is a vampire. He traps Harker in the castle and makes his way to Wismar, bringing the plague in his wake. Only Jonathan's loving wife, Lucy (Isabelle Adjani, The Tenant), recognizes the evil that Dracula represents. As the town's population succumbs to sickness, Lucy resolves to put an end to the vampire's reign, no matter what the cost.

Beyond reverting to the character names found in the novel (Murnau changed them for his unauthorized adaptation to avoid prosecution by Stoker's widow), Herzog mostly disregards Stoker in Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (henceforth referred to simply as Phantom der Nacht to avoid confusion with the 1922 film). His movie seems to exist in a vampire movie vacuum where Murnau told the story first and no one else has bothered since1. Anyone attempting to find a place for Phantom der Nacht in the evolution of Stoker adaptations will find the film anomalous; its closest antecedent was already nearly sixty years old when Herzog's cameras began rolling. Indeed, Herzog actually repeats a number of shots from Murnau's Nosferatu verbatim, a curious move for a director who is an accomplished visual stylist in his own right. Unfortunately, these homages stick out quite a bit -- you can easily pick out many of the shots belonging to Murnau by their tendency toward high- or low- angles.

However, even as Phantom der Nacht maintains an almost slavish devotion to much of Nosferatu, it radically reconsiders its villain. As played by Max Schreck in 1922, Dracula (or Graf Orlok) is an evil being with a face like a rat and teeth to match, the kind of guy who haunts nightmares, an unearthly monster who rises from his coffin as if on a hinge, spreading his shadow to terrifying magnitudes. When he finally dies in the rays of the sun, he fades into nothing, like an image on undeveloped film. Although the Dracula conceived by Herzog and performed by Klaus Kinski still has the ratty features, he is almost the exact opposite of Graf Orlok. No longer a near-intangible malevolent force, Dracula is now a being burdened, weighed down by his curse to never die and never love. There's a palpable physical presence now which undercuts his supernatural existence – the more real Dracula seems, the less unreal he's allowed to be. This causes some conflicts in areas of the film where Herzog remains true to his source. For instance, the unspoken near-psychic connection between Lucy and Dracula is intact here, but it makes far less sense since the vampire has been stripped of much of his mysticism. It is easier to accept a creature of pure evil making waves on the psychic plane than a pathetic, embittered old man.

Additionally, Dracula's purpose in migrating to Wismar is not as clear here, although it's still explicable. It could be argued that the Count is attempting to escape the superstitions of the Transylvanian village folk that impede his ability to feed; their knowledge of his power and their vigilance in spreading the word has probably prevented many meals from walking to his doorstep. However, given his seeming despair at being unable to feel, he could be trying to bring himself closer to the humanity he himself is denied. This is not in conflict with his role as plague-bearer – as he comes physically closer to the living, he draws them to his state of being: death. The plague appears to be a natural consequence of Dracula's presence and not part of an evil plan on his part. He accepts the horrible death of Wismar's population as a consequence of his actions, although he is incapable of feeling remorse for it. Herzog’s Dracula is not evil because he is actively opposed to the values of society, but because his own system of values is substantially different by matter of circumstance.

How much of the characterization of Dracula belongs to Herzog's writing is difficult to say, because Klaus Kinski captures the part so totally that even if he had disregarded every stage direction in his script, it would still feel like it was performed exactly as written, as if he could be portrayed no other way. Kinski is always mindful that Dracula as a more fully-realized character does not necessitate a more human character. The deliberate way that Kinski moves through each scene demonstrates Dracula's despair, but it also makes him look slightly out of synch with the land of the living, as if our gravity is just too strong. In the scene where Dracula watches Jonathan Harker eat, there's this beautiful look in Kinski's eyes, penetrating and creepy and a little confused, as if he's not quite sure how to comport himself while his supper is having dinner.

In a vintage documentary produced at the time of Phantom der Nacht's production, Herzog states that his is “a generation without fathers”2; he says it again in the DVD commentary recorded some twenty years later.3 Herzog means it as an explanation of why films like Murnau's Nosferatu hold such great importance to him. However, there is a recurring motif of impotent male authority figures throughout Phantom der Nacht that adds additional layers to the director's statement. This ineffectuality runs through all levels of society in the film. The city council (government) is so hapless in its efforts to contain the plague that soon most of the city (council included) has died of it. Jonathan Harker (family) attempts to return to Wismar before he has fully recovered from illness, in order to warn Lucy of Dracula's coming; he fails utterly, arriving too late and in such poor condition that he no longer recognizes the wife he is meant to save.

Most prominent of the failed male authority figures, however, is Van Helsing (Walter Ladengast), who holds so dogmatically to the tenets of scientific reasoning that we may as well call him the representative of religion. In a major change from Stoker's heroic sage, Herzog's version of Van Helsing is a doddering old man who denies the existence of the supernatural and assures Lucy that, in these “enlightened times,” vampires cannot exist. Although he means well, he cannot help but patronize Lucy when she attempts to convince him of this very real evil. He keeps on saying, perhaps in an effort to convince himself, that science will find an answer, even though Dracula's plague has already claimed most of Wismar's population, and there are indications it is spreading. When Van Helsing is finally convinced that there are more things in Hell and Earth, his attempt to take action comes far too late; tragedy has already struck and he finds himself punished for his good deeds.

Even with such weak men as foils, the character of Lucy is problematic. Of all the characters, she proves to be the most resistant to alteration from her silent film incarnation, both in terms of script and performance. In Nosferatu, Ellen (Greta Schroder), as the character is called there, is a sensitive, delicate creature, given to fits of hysteria and weird episodes of psychic connection with Dracula/Orlok. Schroder, in keeping with the silent movie milieu, expresses herself broadly, letting her body communicate where words will not. Lucy, in Phantom der Nacht, is also highly emotional and prone to flailing, although she doesn't appear as fragile. Herzog's script frequently has her speaking in bizarre metaphors -- elevated nonsense like "Even the stars, they wander towards us in a very strange way.” Perhaps the intent was to translate the theatricality of silent film performance into verbal expression, but it's an embarrassment, and it becomes even more so when Adjani's performance detours into a wide-eyed duplication of Schroder's. With her arms held across her face, her lip quivering, and her voice spilling inanities, Lucy sometimes just seems like a crazy person. Or a performer at your local coffeehouse's poetry night. Your pick.

As I stated earlier, Herzog is an accomplished visual stylist in his own right, and his multiple pulls from Murnau don't really diminish this fact, even if they do put some strain on the film. There are several visually arresting shots through Phantom der Nacht that envelop the audience in another time and place. Many of these occur during Jonathan Harker's ascent up the mountain to Castle Dracula, as he passes by babbling streams, impossibly deep gullies, and rolling green hills - all bursting with the colors that consummate outdoorsman Herzog would know well. Then, as Harker nears the castle, strange dark clouds roll in, blotting out the sun and finally causing the very frame to fade to black. In the next shot, which features Harker walking down a path in near-total darkness, something has definitely changed. While the film previous to this point had relied on naturalistic lighting schemes, now Harker is lit from behind by some unknown non-diegetic source, clearly indicating that Phantom der Nacht has traversed out of the world of the rational.

Unfortunately, these breathtaking scenes are not complimented by Herzog’s pacing decisions. Phantom der Nacht moves very slowly. Very. Very. Slowly. There's a number of reasons for this -- shots linger for many seconds longer than absolutely necessary, actors take speaking sabbaticals between sentences, and excessive time is spent establishing locations. None of these peculiarities would be a problem if Herzog had undertaken a remake of, say, Murnau's The Last Laugh or Sunrise. However, this is meant to be Nosferatu and Herzog's editing choices defuse tension and drain much of the horror from the story, leaving only a sense of disquiet behind.

F.W. Murnau produced a masterpiece in 1922. Fifty-seven years later, Werner Herzog tried for the same. The result is neither masterpiece nor folly but the kind of near-miss only a genius could create. Herzog's remake is rich with subtext and beautiful in its own way, though waylaid by some unfortunate directorial choices. As fascinating for its flaws as it is for its successes, Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht is still worthy and deserving of the effort to explore its nuances.

This review is part of German Horror Week, the third of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.

1 In the interest of full disclosure, there is one reference made to Bela Lugosi's "children of the night" line from the 1931 Dracula. However, on the DVD commentary for Phantom der Nacht, Herzog claims that he hasn't seen that version. Either he's misremembering or he pulled that bit from popular culture. In any case, it's the exception rather than the rule.

2 "Werner Herzog Talks About the Making of His New Films: 'Nosferatu the Vampyre.'" Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht. DVD. 1979. Anchor Bay Entertainment, 2004.

3 Herzog, Werner and Norman Hill. Audio Commentary. Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht. DVD. Anchor Bay Entertainment, 2004.

If the line referenced in the

If the line referenced in the first footnote is the "(...) the children of the night... What music they make!" line, then I believe that line actually does appear in the original book, so it may not be a reference to the 1931 movie.

"Children of the night"

"Children of the night" appears in Chapter 2 of Bram Stoker's novel: "Listen to them, the children of the night. What music they make!" Seeing, I suppose, some expression in my face strange to him, he added, "Ah, sir, you dwellers in the city cannot enter into the feelings of the hunter." The dialog is used almost verbatim in Herzog's film.

I am really impressed with

Thank you for the kind words!

Thank you for the kind words! This site has been a labor of love for me.

To answer your question: the layout/theme is a custom one I designed myself.

"He went for a little walk! You should have seen his face!"