Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

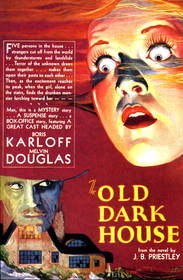

The Old Dark House (1932)

In the horror genre, when a house stands out as a primary component, it is often going to be haunted. In The Old Dark House, however, director James Whale uses a house in a different, more rewarding way: as a metaphor for the psyche. Things like seldom-visited rooms, locked closets, and at-odds inhabitants provide rich ground for such use. The fact that these elements succeed in achieving a level creepiness on par with that of your average haunted house film says something rather unsettling about the way our heads work. The Old Dark House is a house-as-head movie that examines repression, fear, and the role of the new, constructed with the adeptness one would expect from the great James Whale.

Three travelers - a married couple, Philip and Margaret Waverton, and their friend Roger Penderel -- have been caught in a torrential storm and, seeking shelter, find themselves as guests in the mansion of a particularly dysfunctional family. The house belongs to a man named Horace Femm, who occupies it with his mute butler Morgan, his ostensibly deaf sister Rebecca, and, we soon learn, two others: their father, Sir Roderick, who lives upstairs on the verge of death, and their brother Saul, who is kept locked away due to his arsonist-homicidal tendencies. Soon after, two additional stranded travelers arrive: Sir William Porterhouse, a man who lives up to his name in every way, and his mistress-sans-sex, Gladys Perkins, a woman who is openly involved with Porterhouse purely for the money. During the night of their stay in the old, dark Femm house, these five visitors, as well as those who live in the house, will all experience the shock of change, ignited by the most repressed of the household.

The psychological metaphor is constructed with a firm foundation. Rebecca personifies the superego, operating as if she is the authority of the household. She listens to others neither literally nor figuratively and is always quick to bark half-heeded orders and admonishment, even to un-provoking guests. Most often these orders relate to physical and spiritual safety. All of her energy is devoted to telling others how they should be. Morgan is a definite portrayal of the id. He is prone to drinking, destruction, and attempts at upheaving the household's status quo. Furthermore, he cannot speak and thus remains an unexplainable entity, forever unable to provide a reason for his actions. It is fitting that he is played by Boris Karloff, who just one year before played another id-character: the monster in Frankenstein (also directed by Whale). In the middle sits Horace, the ego, simple self-awareness. Horace is a man tortured by the opposing sides of his psyche even while he rejects them. Most of his actions seem either responsive to his superego (Rebecca) and id (Morgan) or, towards strangers, passive (allowing just anyone to eat his food and spend the night in his mansion, for example). He is pleasant and carefree, except for when it comes to his family. With this setup, the script falls naturally into place.

Interestingly, what Horace fears most of all is not Morgan, the id itself, but the evil that the id is capable of releasing, Saul. It is Morgan who takes care of Saul, the crazy brother banished to his room for life, a room that Horace is not willing even to approach, and it is Morgan who holds the key to the room. Saul is eventually freed from his room, and what ensues eventually leads to the film's understanding of conflict as a vehicle to peace and contentment. Upon release, he causes precisely the havoc that it was warned he would attempt.

In the end, Penderel stops Saul from burning the house down, and Saul is eventually killed in a fall that ensues during a scuffle between the two. Morgan essentially disappears, presumably to his quarters of the house. Rebecca loses her authority and resorts to scowling at Philip and Margaret from a window, frustrated with their sexuality. All of this follows the psyche metaphor by illustrating the power of introduction of new ideas, and the film becomes an observation of the ability of outside influences to diminish the power of the id and superego. Through the tempest of the night's events, Horace's fears have been cleared away. The next day he is bright and cheerful, just as the new day is bright and sunny, as if nothing but a cleansing had occurred. In The Old Dark House, motivation and happiness are dependent upon more than the inner-workings of the psyche; they rely also upon flanking, alien ideas. For years, Horace had been locked up with little more than the superego and id to keep him company, and by the looks of things, those years were gloomy at best. With the arrival of a few visitors, he is able to purge himself of that misery.

Because of the metaphorical nature of The Old Dark House, the plot is able to meander with no real destination and still remain interesting. For the most part, the characters walk about the house and converse with each other, each word containing some degree of meaning because each character is important. There is rarely the sense that there will even be a climax, though we do eventually get one. Occasionally something slightly foreboding happens, such as Philip and Margaret's conversation with Sir Roderick, to retain some level of tension. This lack of overt linearity in the plot gives the film a natural feel, like we are watching people simply going about their business in a slightly abnormal situation, as opposed to characters proceeding through calculated events.

On the more concrete side of things, I would be remiss not to mention the film's two most well-known actors: Boris Karloff and Ernest Thesiger. Boris Karloff is the first actor listed in the opening credits (in all caps no less) and is even the subject of an introductory producer's note, but his role as Morgan the mad butler is nothing more than supporting. Nevertheless, he plays it perfectly. From his first appearance, a slow reveal through an opening door, his demeanor is always depraved. Even when he serves Horace, Rebecca, and their guests at dinner, his slight hunch, emotionless face, and uncaring eyes fully characterize him as someone who has been rejected from even his immediate family's affairs.

By contrast, Ernest Thesiger provides a so-so performance here. The actor often does too much to make it perfectly clear that he is always at the influence of his sources of shame and fear. When Rebecca admonishes him for disrespecting her stringent devotion to Christianity, he cowers and looks up like a scolded puppy. Later, when he is basically forced to fetch a lamp that has been stored near Saul's room, he lies and says that it's too heavy for him, that Philip should get it instead. Philip asks if it will be too heavy to carry by himself, and Thesiger's character responds, "Oh, no, not at all. It's quite light, really." Caught in his lie, he widens his eyes, makes an "O" with his lips, and puts his hand to his mouth (go ahead, do the same right now while reading this review, and you'll likely get a feel for how silly it looks), demonstrating not the actions of a frightened man but of a naughty child. The rest of his performance is adequate and less cartoonish but nothing of the quality we would see three years later in Whale's Bride of Frankenstein.

The Old Dark House is not very scary. In fact, most of its horror elements are internal, relying on a response from the characters rather than the audience. Its success as a film lies not in evoking feelings of fear or repulsion but in examining psychological make-up through a metaphor. It may in fact be best classified as a drama, since it relies mostly on characters' interactions with one another. More than anything, this film is well-written. One could almost teach it in an English class. If only teachers were so cool.

To me, the most interesting

To me, the most interesting thing about watching The Old Dark House was realizing I was watching the progenitor of all the "motorists get stuck and make the mistake of going to the nearby house" movies made since. I sat there thinking "This was the forerunner of Rocky Horror Picture Show *and* Texas Chainsaw Massacre..."

That's interesting. It's

That's interesting. It's become such a staple of horror that I never noticed that.