Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

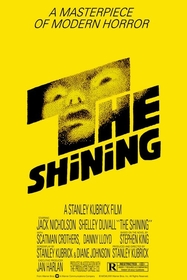

The Shining (1980)

Stanley Kubrick's The Shining is one of the best horror movies ever. Just look at how frequently it ranks on "All-Time Best Horror Film" lists. It is a Rorschach test reflecting one's relationship with terror because it serves modern audiences a complex visual and narrative metaphor that represents the struggles individuals, institutions, and nations suffer when they overlook their own terrorist impulses. The film literally bleeds with impressionistic, atmospheric gloom. That's what you get when you throw into the blender the ideas of three talented artists at the top of their game: Stephen King, Jack Nicholson, and Kubrick.

Nicholson plays Jack Torrance, a former teacher turned writer who procures employment as the winter caretaker of The Overlook Hotel located in Colorado's reclusive mountains. His wife, Wendy, and son, Danny, accompany him. Although the manager warns Torrance that another caretaker, Delbert Grady, murdered his wife and twin daughters with an axe because of "cabin fever," Torrance is unfazed. The solitude required for writing is exactly what he needs.

Their introduction to the hotel begins innocently, but events quickly change. Danny, who possesses a unique paranormal ability to see into the past and future, connects with another kindred spirit, the cook Dick Hallorann, who also can "shine." Danny begins "shining" and witnesses flashbacks of the Grady murders. As Danny's state deteriorates, Wendy becomes more concerned and blames Torrance for Danny's condition. Torrance methodically loses his sanity as the weather, space, and time close in on him, and through a series of hallucinations, former inhabitants of The Overlook, namely Grady, slowly push him over the edge and suggest that he "correct" Wendy and Danny for their transgressions. What unfolds are some of the most classic scenes in horror history depicting Torrance's brooding figure stalking his wife and son through the hotel's labyrinthine rooms and outdoor maze.

This is Kubrick and Nicholson at their best. Sure, their filmographies rank as two of the most impressive in recent decades, but here they are unrelentingly over the top. Nicholson said Kubrick's maddeningly meticulous style almost drove him over the brink; subsequently, they never worked together again. The DVD, released in 1999, contains a documentary produced by Valerie Kubrick, the director's daughter, who was 17-years-old at the time. The documentary is interesting because of its content, particularly the footage depicting the power dynamics between Kubrick and his two main actors: Nicholson and Shelly Duvall - but it is sophomorically produced. Surprisingly, Dad let her miss this opportunity to shine (no pun intended).

As perhaps the ultimate auteur, Kubrick's personal tenet about the role of a director could easily serve as the mantra for auteurism: "one man writes a book, one man composes a symphony, it is essential for one man to make a film." His imposing directorial style leaves no aesthetic stone unturned, and his work has been called everything from brilliant and ingenious to arrogant and incoherent. In The Shining, those talents are unleashed with passion.

Kubrick always redefines visual space, and he is particularly fascinated with humans' relationship to space. Whether it be cosmological space in 2001: A Space Odyssey, or the space and subsequent distance in levels of the military bureaucracy in Paths of Glory, Kubrick suggests that our relationship to space defines our existential space and meaning. Torrance's character is a perfect example of this. The Overlook Hotel, whose interior shots were built on the back lot of EMI's Elstree Studios in England (the exterior shots are of the Timberline Lodge in Mount Hood, Oregon), is a classic haunted house. The hotel and its surrounding environs are a metaphor for Torrance's psychological state. As a fledgling writer, he is empty of ideas. Like the snowdrifts outside, Torrance is professionally drifting. And like the extreme cold outside, he too is becoming personally cold and detached.

Kubrick's ability to tackle different genres is noteworthy, and his personal signature of being unconventional has redefined each. The Shining is a perfect example. The film's first half is relatively bloodless; most of the horror doesn't appear until the film's climactic ending. Prior to that, psychological horror reigns; the horror is only imagined in the characters' minds through flashbacks, flashforwards, or hallucinations. Also, most of the film is shot during the day, and some of the most riveting scenes occur in splashes of bright daylight. This unexpected light casts his photographs in a dream-like state. Perhaps The Shining is a nightmare Torrance experiences while writing his fiction, one where literal reality is suspended and everything becomes metaphor. One shot midway through the film where Torrance wears a green sweater and stares out a window into daylight, his head slightly pointed downward, is as menacing as they come. The blank orbs in his eyes still haunt me.

I'd rather have this bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy. Jack Nicholson in Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980).

I'd rather have this bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy. Jack Nicholson in Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980).And Kubrick's monster, which is what Torrance becomes, is remarkably ineffective. He only kills one person and fails miserably in stalking his family. What kind of monster is that? Wendy bashes Torrance's head in with a baseball bat, and in his subsequent fall, he suffers an ankle sprain. She also slashes him with a knife. Clearly, his victims perpetrate more violence on him than he does on them. At one point, he is even locked in a dry goods pantry (real tough!), and in a moment of narrative discontinuity, is released by a ghost. By the film's end he is depicted as a blithering idiot that dies foolishly of hypothermia in the outdoor maze. Kubrick's "revisionist monster" is an important element in the film because it reminds viewers that this is no ordinary horror film. In fact, the narrative and its genre-based trappings are a red herring for something far more complex: a political and societal commentary that often escapes casual viewers.

Kubrick's Steadicam shots also create unease. Like Hitchcock, Kubrick imposes his presence on viewers. Often, these steady shots undermine our feelings because they depict tense scenes. A hand-held camera technique, so popular in horror films, would seem more realistic. But Kubrick mostly abandons that technique to allow the camera itself to create discomfort. The slow dolly shots, pans, and zooms have a similar effect. We don't want to penetrate the unfolding terror before us; however, Kubrick refuses to let us off the hook. He traps our perspective within the camera's and slowly escorts us into increasingly more intense layers of horror.

The composition of The Shining also creates an awkward feeling of order vs. disorder. Kubrick's sense of mise-en-cine conveys visual and narrative power. His shots are almost always balanced, proportionate, and clean, so much so they reek of being unnatural. But their visual appeal enriches our viewing experience, and we focus more intently on the scene's details. At other times, we are distracted, and when the actors redirect our attention, we are shocked into attention. Furthermore, his orderly approach to composition undermines the disorder happening in the narrative. The further the Torrance family slides into paranoia and madness, the more geometric the compositions become; they ultimately find themselves in the outdoor maze.

Some critics suggest the film is fundamentally about racism and America's closet history of genocide, slavery, and imperialism and argue the film is a metaphor for America's treatment of Native Americans and, to a lesser extent, African Americans. In 1987, Bill Blakemore of The San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "Kubrick is examining in this movie not only the duplicity of individuals, but of whole societies that manage to commit atrocities and then carry on as though nothing were wrong. That's why there have been so many murders over the years at the Overlook; man keeps killing his own family and forgetting about it, and then doing it again."

The evidence he provides is illuminating. The film is filled with stereotypical Native American imagery. The opening chords from Verdi's "Dies Irae" (Latin for "Day of Wrath") are typically used in Roman Catholic funerals (but nobody has died yet?), and the lone moving image in the opening footage is a Volkswagen, a byproduct of Nazi Germany's war machine. Not coincidentally, the only person killed in the film (besides Torrance) is Hallorann, a black servant, who, when he dies, lands on a Native American image carved in the floor. The eerie and inexplicable scene that depicts blood gushing from the elevator, in this context, is the blood spilled by American imperialists. The Overlook Hotel itself is an imperialist getaway for the rich, a mini-empire built on sacred Native American grounds (even a few Indians were repelled during its construction).

The Shining suggests that the perpetrators of such violence cannot hide forever. No matter how hard one "overlooks" these realities, they will be found. The two who can "see" the hidden atrocities are a minority, Hallorann, and Danny, a member of the next generation, the only entity that can right these wrongs. Kubrick's political answer to this age-old dilemma is clear: the solution to breaking this vicious cycle of overlooking unsavory historical pasts can only be found in an empowered citizenry buttressed by a nation's youth that listens to victims' stories, and instead of hiding the past, delves directly into it, revises the inaccuracies, and provides a platform for forgotten voices.

This reading is particularly useful in the context of our post-9/11 world because The Shining is a haunting reminder of America's terrorist past. The film posters used in Europe to promote the film read, "The wave of terror which swept across America." This is an obvious reference to the film itself, but it also serves as a clue in understanding one of the film's many themes. The wave of terror is American imperialism, an impulse fueled by the notion of Manifest Destiny. Kubrick clearly tries to evoke this notion in the opening scenes of the vast mountains and prairies of America's Wild West.

Another important theme in the film addresses the dangerous allure of pop culture fame. Kubrick is brave for pursuing this theme, because much of his popularity as a filmmaker is embedded in it. As Mark Steensland of Kamera.co.uk.com suggests, Torrance has clearly committed the first major flaw in succumbing to pop culture fame: he has quit his day job (as a teacher) to become an artist (a writer in this case). This has uprooted his wife and son, and although they recover, they are terrorized in the process.

The film is riddled with pop culture references, and they are often used in derogatory ways. Torrance says Wendy will have no problem with the "real" horrors at The Overlook because she is a horror film junky. As the Torrances approach the hotel, Danny recites a story he heard on television about a family that ate its relatives. Torrance's sardonic reply? "He's OK. He saw it on television." Danny is called "Doc," an attempt to soften him into a cartoon character, and when Jack butchers the bathroom door, he recites the "Three Little Pigs". Clearly, Kubrick is poking fun at the ironic way pop culture is used.

Torrance's whim of becoming a writer is also an example of his duality. Once a teacher, he has now chosen to hide that part of his past to become something sexier, more fashionable and popular. And his talents as a writer are questionable at best. He produces nothing for his "new writing project," and one wonders if this project is simply a mid-life crisis gone berserk. There is danger in denying who you are, Kubrick is suggesting, especially if you are molding your personality after pop culture images.

However, The Shining does have a number of flaws. Danny at times acts like cardboard, but overall, he adequately portrays a confused and psychically challenged boy. Early in the film, Wendy seems too subservient to Torrance and too frazzled to accomplish anything, but her dizziness is perhaps deliberately designed to parallel her poignantly terrorized expressions in the film's conclusion, and ultimately, her escape. Earlier, she seemed incapable of escaping anyone; near the end, Torrance becomes the dunce. The film could easily lose 15 minutes of footage, particularly the subplot of Hallorann traveling to The Overlook to help the Torrances. I'm not sure what this adds other than a slight deviation from the at times oppressive focus on such a small cast.

The film's greatest confusion occurs when trying to identify continuity in the "shinings" and their overall purpose. They possess an internal logic, but understanding it often distracts viewers. At first, only Danny and Hallorann can shine. But eventually, everyone shines. Is this because they all share this paranormal ability? Or is it because The Overlook's ghostly inhabitants have equally haunted them? Or is "shining" a metaphor for seeing the ugly truth behind people's lies? Or perhaps a metaphor for revisionist history? These are difficult questions to reconcile after analyzing the film several times let alone watching the film once or twice.

Nevertheless, I can forgive these flaws because the message is far more provocative. The film is a fundamental experience for anyone seeking to understand American history and how one innovative artist sought to represent it. The Shining truly is Kubrick's version of American history. The film's status in the horror camp has detracted from its overall value in film history. It is not just a great horror film; it is a psychological profile of how people wrestle with their unsavory pasts. That is something that should not be limited to horror. We all should do this, especially in these trying times of terror.

Trivia:

The Louisville Slugger that Wendy whacks Jack with is signed by Carl Yastrzemski.

Kubrick would call author Stephen King at 3 AM and ask him strange questions, such as, "Do you believe in God?"

I wonder if the entire genre

I wonder if the entire genre of science fiction films, slash films, and violent ganster and crime drama/action films are not elements of a broader cultural disposition in America. We are the purveyers and the creators of this genre for the world. Early European and Japanese versions do not repeat the same formula of hidden monsters, unknown terror, and gratuitous violence that seems to be the milk of popular cinema in the United States. What is the underlying trauma that seems to motivate these films and the constant fear that make them so popular to audiences?

Great article and analysis as