Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

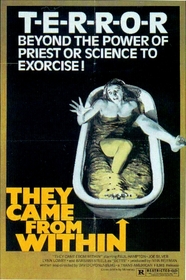

Shivers (1975)

Although Shivers is not technically David Cronenberg’s first film (he had made some art films previously), it should be considered his debut. Shivers boldly announces the arrival of a creative mind able to concoct horror movies layered with subtext and commentary that don’t forget to entertain at the same time. One can clearly recognize the work of a mad cinematic scientist with preoccupations never seen before (and only imitated since). However, Shivers also betrays a shaky young gun whose bold vision is frequently undermined by his tenuous grasp of the tools at his disposal. The result is a movie that fares better when submitted to a literary critique than a standard movie review.

Shivers (also known as They Came from Within) opens with a slideshow presentation extolling the virtues of Starliner Towers, an isolated apartment complex/community outside of Montreal that promises all the conveniences of modern living. Within this glass-and-steel monument to the bourgeoisie, however, parasites from an experiment gone wrong have escaped, infecting the populace one at a time. Those affected are stripped of rational thought, becoming sexually crazed, zombie-like madmen. It’s up to Dr. Roger St Luc (Paul Hampton), Starliner’s resident sawbones, and Nurse Forsythe (Lynn Lowry) to either contain the epidemic or escape the chaos.

When the writers of the French film magazine Cahiers du cinema were first molding what would become known as the “auteur theory” – the idea that certain directors are the single creative force of their films – they couldn’t possibly have imagined a more appropriate or perfect example than David Cronenberg. All of his genre work is preoccupied with the same themes – among them the revolution/evolution of the body, the confluence of sex and disease, and the banality and repression of modern society – yet each film explore these ideas in different ways. Shivers acts largely as a primer to these obsessions, introducing them to the unsuspecting audience in bold, unmistakable terms.

Most important of all of Cronenberg’s themes is the body as a political entity that revolts against the self, usually as a result of some sort of technological catalyst. In an early scene in Shivers, a scientist discusses a project to create a benevolent parasite that could take the place of a diseased organ. We learn later that another scientist, Dr. Hobbes (Fred Doederlein), has successfully engineered just such a creature to replace what he considers to be the most diseased organ of all – the over-thinking, over-rational human brain. Once the parasites enter the host body, they reside in the stomach (home of the appetites) and pumps a drug into the bloodstream. The effect of the parasite on the infected differs from host to host – some commit acts of sexual violence, others simply bask in their new freedom. All have been stripped of two important things – their inhibition and their ability to care about that loss. These are replaced by a desire to continue to spread the parasites, to propagate the new species.

This drive to propagate leads us to another of Cronenberg’s themes – the confluence of sex and disease. In fact, this particular concept is stated more clearly and forcefully in Shivers than the bodily revolt, mostly as a result of the “sex parasite” angle. A sign in Dr. St Luc’s office states, “Sex is the invention of a clever venereal disease.” It’s not only darkly humorous, but could be a tagline for the film itself. The disease in Shivers not only passes by sexual contact – it is sex. The parasites themselves – long, brown, and squirmy – resemble grotesque parodies of male genitalia. Cronenberg also positions them as having the similar functionality to the penis in two scenes. In the first, Nicholas Tudor (Allan Kolman), one of the earliest victims, lies in bed, peering at his stomach where multiple parasites are incubating. He begins muttering frustrated encouragement as he looks down his body, as if talking up a reluctant erection instead of a venereal parasite. The second scene takes place in a bathtub, where repressed lesbian Betts (horror legend Barbara Steele) is relaxing when a parasite, having wormed its way up through the drain, violates her vaginally. This act of penetration becomes a sexually transformative act, opening her to pursue her desire for neighbor Janine Tudor (Susan Petrie).

Amidst this sexual apocalypse, Cronenberg also asks us to question the worthiness of the society that it threatens to upend (so to speak). He seems to find modern living and modern man dreary and even hypocritical. For instance, the advertisement for Starliner Towers that opens Shivers promises a community of friends and neighbors, even as it promotes the building’s isolation from the rest of the city. The narrator (later revealed to be the rental manager for the complex) speaks with a lulling, almost hypnotic cadence that seems to inspire trust through its passivity. Cronenberg then puts to lie the ad’s idyllic promises by following it with a disturbingly violent sequence where Dr. Hobbes strangles a young girl to death, strips her body naked, slices open her stomach, pours acid in the incision, and then runs the scalpel across his own throat. Intercut with this seemingly meaningless aggression is a small bit where Starliner’s rental manager discusses apartment options with a married couple, creating a grotesque juxtaposition between the brutality and the banal.

Indeed, violence is another target of Cronenberg’s societal critique. Physical aggression runs rampant throughout the film, from both the infected and the uninfected. However, the infected’s depiction as single-minded, driven animals acts as their absolution. They are merely following a biological imperative to spread the parasites and grow their population. Really, we can judge them no more harshly than the average subject of an Animal Planet documentary. The rational, “normal” humans don’t have any such excuse. Their violence is always more destructive. First, there’s the scene at the beginning with Hobbes attack on the girl – although we can justify that once we learn that the girl is Patient Zero in the parasite project. Later, the cool and rational Dr. St Luc becomes like an angel of death for the infected, offing several of them. In one scene, he is attacked by one – a man – who proceeds to kiss him on the back of the neck. The two get into a scuffle which ends when the doctor beats his assailant to death with a crowbar, his face a portrait of disgusted desperation that seems more like gay panic than self-preservation. For the rest of the film, he wields a gun with which he can coolly dispatch his adversaries from a distance, usually with one more bullet than is absolutely necessary.

That so much can be said about Shivers themes is not, as it would seem, an indication of a high level of craftsmanship on the part of all involved. Looking at the film, whose individual parts work just about as often as they do not, simply indicates that Cronenberg’s thematic concerns and the force with which he states them manages to overcome some inconsistent filmmaking.

First, though, let’s look at the production history behind Shivers, because it largely acts as an explanation and (probably) an excuse for its issues. In the early 1970s, Cronenberg – having made two short films and two features for the arthouse crowd – was trying to sell a script called Orgy of the Blood Parasites. The trouble was, he was in Canada, which was not a country known for its horror films. Eventually he approached Cinepix, a company that mainly dealt in softcore pornography. Despite Cinepix’s attempts to surreptitiously offer the project to other directors (including Jonathan Demme, later of Silence of the Lambs), Cronenberg was eventually allowed to helm his own project. On limited money and with no real experience in commercial film, Cronenberg used Shivers as a learning experience, teaching himself to direct as he went.

When one looks at Shivers, it becomes apparent just how much Cronenberg had to learn. Several scenes throughout the film are just sloppy – poorly framed, visually awkward, or just plain dull. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these are typically either talking scenes (casual conversation, expository dialogue) or silent business (walking down corridors, entering a room). During scenes of horror, particularly when free range parasites are attempting to insert themselves into a new host, Cronenberg seems to have a much better idea of what he wants, utilizing low angles and tighter, more controlled shots. I can think of two possible reasons for the discrepancy. One, the easy scenes that didn’t require a lot of special effects or action choreography might have been shot earlier, giving Cronenberg ample time to develop the confidence he needed for later, more difficult scenes. Alternatively, perhaps Cronenberg was simply more comfortable with the fantastic elements of the story and had trouble finding a creative voice for the human element. Either is likely and I believe it was probably some combination of the two factors, although I don’t have much in the way of proof.

Cronenberg’s own script gave him plenty of those horror-action pieces to work with – too many, in fact. Nearly all of the thematic goodness shows up in the first two-thirds of Shivers. After that, the film eases into a repetitive third act that follows Dr. St. Luc and his nurse as they alternately attempt to escape Starliner or hide from the crazies within. There are several effective moments in this section, as Cronenberg shows the different kinds of sexual proclivities that the parasites awaken – really taboo desires like incest and pedophilia (both, thankfully, suggested rather than shown). No-one is immune – young and old, beautiful and ugly rut together indiscriminately. One just wishes these bits didn’t appera to exist purely for their shock value, that they added something to the impressive ideas relayed earlier. Alas, no. Cronenberg’s script seems to say, “You’ve had your brain food. Now we’re just going to get weird.” It’s a disappointing turn that makes the film feel poorly structured.

Shivers also has problems sticking with a protagonist. The beginning of the film seems to position Janice and Nicholas Tudor as our dramatic throughline and we expect the plot to deal with the infestation from Janice’s perspective as she deals with her husband’s changing (infected) personality. Then we’re introduced to Dr. St Luc, and soon after his nurse, and the film bounces between the two pairs of characters before relegating the Tudors to the background. Mixed into all of this is the curious suggestion – one lent credence by Cronenberg’s adeptness at the parasite scenes – that perhaps the real protagonist is the disease itself. Certainly the infection gets more quality screentime than the normal human beings, and Cronenberg has stated that he sympathizes more with the characters in this movie after they are infected. It’s almost as if the human perspective is a perfunctory plot device, which Cronenberg only added as method through which to relay the disease’s story to a human audience.

Truthfully, one might not mind an all-parasite Shivers after dealing with the performances of the human actors. With the exception of Barbara Steele (always magnificent), the cast is almost unilaterally below average. Particularly poor is Paul Hampton as Dr. St Luc. Speaking in a flat, unaffected voice and staring off at some nonspecific point off-camera throughout the film, he fails to interest us in the plight of his character. By the film’s middle, we hope he does get a parasite in the stomach, because maybe he’ll liven up a little.

Given the dichotomy of this review, you wouldn’t be blamed to think that there are two completely separate perspectives you can take while watching Shivers – thematic or entertainment. However, each part of the film serves the other – the entertainment illustrates the themes and the themes enrich the entertainment. Much like the parasites and human beings in the movie itself, theirs is a symbiotic relationship. It’s not often pretty, but it does usher in a new vision of society, undeniable and inescapable, even if exists only in the head of David Cronenberg.

You just put all the nails on

You just put all the nails on their right place. I bought the movie and watched it with the greatest of all expectations, and in the end, if not disappointed, I ended up pretty confused. I knew I was before a very thematically-rich movie, but I felt bored at certain moments. Comming from the same guy who remaked The Fly in the most awesome way, and who brought us such surreal -and entertaining- experiences like Videodrome, The Brood and Rabid, I did expected a little -just a little- more than delivered. In the end, it was like: "Come on, don´t be so hard on the guy. It was his first real try on horror and it went okay", but reading your review just let me know what was bothering me about this movie. And for that, I thank you a lot.

Best regards

Ricardo Aguado Fentanes

Thanks! That's one of the

Thanks! That's one of the highest compliments a film critic can receive!

"He went for a little walk! You should have seen his face!"