Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

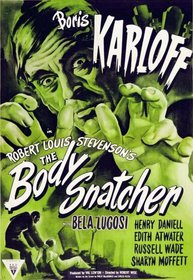

The Body Snatcher (1945)

"You'll never get rid of me that way, Toddy," the sinister cabman Gray intones to his "friend" Dr. MacFarlane, and we believe him. We have to, as it is Boris Karloff's mellifluent voice that delivers the promise, and director Robert Wise has presented Gray up to this point as someone who could deliver on his sinister assurance even after the television has been shut off.

Produced by Val Lewton's "B" unit at RKO in 1945, The Body Snatcher utilizes the same Freudian psychological tropes that made previous films by the unit -- Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie -- such critical (and financial) successes. In the case of The Body Snatcher, we are drawn into the downward spiral of two men locked in a struggle of mutual hatred and dependence.

Loosely based on Robert Louis Stevenson's short story (itself an extrapolation of the heinous deeds of "resurrection men" Burke and Hare), The Body Snatcher takes place in Edinburgh, circa 1831. In this period, cadavers necessary for advancing medical knowledge are in scant supply. Some unscrupulous doctors, like Dr. MacFarlane (Henry Daniell) rely on the talents of graverobbers to secure specimens. Gray is such a graverobber, and he uses his invaluable position to continue a long-standing tradition of tormenting his "old friend" MacFarlane. The doctor finds his cold, gruff exterior slipping as despair takes hold. When he attempts to wrest a little peace of mind away from the maliciously jovial Gray, the consequences to all are dire.

Perhaps attempting to keep the creative well of his horror films from stagnating into repetition, Lewton moved away from the modern American settings of Cat People and The Seventh Victim and made a film firmly in another time and place. Even in this, the producer was careful to give The Body Snatcher a richly historical feeling, primarily by utilizing standing sets from RKO's lavish 1939 production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The cobblestone streets of Paris, with a modest amount of redressing, easily transitioned into 19th Century Scotland. To maximize the use of a very few exterior sets, director Robert Wise kept the cinematography tight, often making use of deep focus to artificially "lengthen" the sets -- a trick he no doubt picked up from Orson Welles while editing Citizen Kane.

The script was initially written by Philip MacDonald and used Stevenson's story as a jumping-off point. Key scenes and snatches of dialogue from the story appear more or less intact, but the roles and relationships shift significantly. However, the most frightening and effective part of the film -- its rain-soaked climax -- is lifted directly from the source material. Roger Corman would use the same trick some 15 years later when adapting Edgar Allan Poe -- the original story would become the ending to the film. Interestingly, the other credited writer on The Body Snatcher, "Carlos Keith," is actually a pseudonym for Val Lewton himself. The producer rewrote all of the films he produced to some extent, but he hated publicizing the fact; he felt it fell within his normal duties. With The Body Snatcher, the Writer's Guild of America determined that the changes Lewton made were significant enough to merit an on-screen credit. Rather than put in his own name, Lewton substituted a penname he used for a series of cheap romance novels in the early 1930s.

Like all Lewton films, The Body Snatcher is marked by the complexity of its characters. Take the almost mawkishly naïve Fettes (Russell Wade), MacFarlane's lab assistant. At first glance, he appears to be little more than a bright-eyed protagonist, a point of sympathy in a melange of compromised morality. However, Fettes is no less compromised over the course of the movie than anyone else -- it's just that the rest of the characters have a head start on him. Disgusted and indignant at MacFarlane's receipt of illicitly garnered research specimens, Fettes shows the hypocrisy of his morals soon after he becomes involved in the plight of a disabled little girl. Informed by MacFarlane that the operation to fix her paralyzed legs would be impossible without further study on cadavers -- cadavers they simply do not have -- Fettes takes a walk into the nasty part of town and pleads with Gray to acquire a body as soon as possible. This request leads to a horrific act by Gray that leaves the young medical student unwittingly complicit with a murder. The only shame in this subplot is that the blank-face Wade is unable to carry its weight fully, and nearly exhausts his limited talent trying.

Such is not the case with either Karloff or Daniell; the two form the double patter of the film's dark heart. When Karloff's Gray is first introduced, he comforts the disabled child and lets her pet his horse. Here he is very much as the screenplay describes him - "his face is cringing with good humor and servility." Soon after, we come to know the cold, brusque MacFarlane. He frames his entire world view in terms of the greater good -- and essentially tells the sobbing mother that helping her paralyzed little girl would be an inconvenience. His goals may be noble, laudable even, but his approach leaves him distinctly unlikable.

From there, we are shown far different views of each man. Gray's next appearance comes in the cemetery, where he clubs a yapping dog to its demise before pilfering the corpse of a young boy from the grave. This and subsequent scenes make Gray's outlook very clear -- he does what suits him to get by. MacFarlane, on the other hand, is shown to be warm and passionate when in the embrace of his mistress, Meg (Edith Atwater). Even then, he treats her like a dirty secret, and by day she acts as his housekeeper. Only when no-one else is around does the doctor allow his feelings to show.

More important than Gray and MacFarlane as individuals are Gray and MacFarlane as a self-destructive, self-loathing unit. On a very basic level, the lower class cabman and the upper-crust doctor appear to have a standard employer-employee relationship -- MacFarlane pays Gray to steal bodies necessary to medical advancement. However, MacFarlane could not act any less the superior when he's with Gray; the "employee" knows too much of the "employer's" sordid past and delights in using this power to put his bitter disposition into sharp relief. He uses a simple verbal cue -- MacFarlane's old nickname "Toddy" -- to begin his smirking reminders of crimes past, and he always gets the flustered response he desires.

There is also a deeper, metaphysical link between the two, one that makes Gray entirely necessary to MacFarlane, even if neither man realizes it fully. The cabman is the doctor's alter ego, his ruddy-faced conscience. We best observe this connection in a taut scene at the tavern where MacFarlane pours his way into a drunken stupor after a failed operation. Gray invites himself to sit across the table, taking delight in watching the great and proper Dr. MacFarlane descend into drink. MacFarlane accepts the company, even as he looks down on it, and begins to demonstrate with a stack of glasses why his brilliant ministrations should have, must have worked. Gray dashes the stack to the floor with a violent sweep of his arm. "You can't fix people like building blocks, Toddy," he explains, grimly laying out why MacFarlane is merely a craftsman, not a physician. Finally, he forces his "friend" to look in the mirror; the reflection emphasizes the men's physical dissimilarity, but it also binds them -- two very different bodies, but only one complete soul.

Their relationship comes to a head as the film nears its conclusion. No matter what they do, the pair find themselves fastened to each other by cruel, ironic fate. To reveal too much would be doing the film a gross disservice. Suffice to say, Daniell's performance in the finale makes the sequence as memorable as it is, although the breakneck pacing (there's an edit every few seconds) helps in hurtling the film to its tragic conclusion.

As a brief aside, The Body Snatcher is the last film that Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi acted in together. Lugosi's role as one of MacFarlane's servants is small and pitifully acted. He's dominated by Karloff in both of their scenes together. It's a sad end to a classic marquee pairing, and it mainly serves to emphasize the malevolent brilliance of Karloff's acting, with no benefit to our opinion of Lugosi.

Chilling, complex, and artfully told, The Body Snatcher is the kind of shivery cautionary tale relayed in front of fireplaces on cold winter nights. Each character makes their own contributions to the tangled web of human failures, and we can't help but recoil in both fear and recognition. That kind of horror stays with you, lingers at the back of your brain. You'll never get rid of it, Toddy... Never.

One thing you didn't mention

One thing you didn't mention was that some of Karloff's lines were funny and said with such deadpan the humor in them might go over some heads. I wasn't expecting such a well written script acted with such brilliance although Bela Lugosi could have just phoned in his part and it would have been just as good. I wonder if his drug use was the cause or if that came later.

The trailer for this film

The trailer for this film claimed "The Hero of Horror Boris Karloff joins forces with the Master of Menace Bela Lugosi in the unholiest partnership this side of the grave!" This gave the illusion that they actually shared significant screen time. One wonders how the audiences of the day reacted when they realized they had been duped by clever editing!