Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

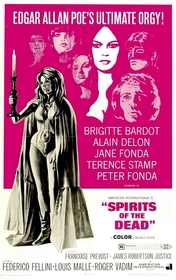

Spirits of the Dead (1968)

If you're familiar with the works of Edgar Allan Poe, you know that amongst his most prominent themes is that of the past's ability to terrorize you. The three loosely adapted Poe stories in Spirits of the Dead - "Metzengerstein," "William Wilson," and "Never Bet the Devil your Head" - are about exactly that. Though they are each helmed by a different director, the continuity and quality that flow through them are perfectly consistent, creating an experience that is well-told, layered, and haunting.

The first segment is "Metzengerstein," directed by Roger Vadim. "Metzengerstein" stars Jane Fonda as the depraved Countess Frederique of Metzengerstein. Frederique is the sole heir of her family's fortune and reigns over the estate with an occasionally maniacal impulse. She spends her time doing little more than killing, tormenting, and fornicating. One day, though, Frederique astonishingly demonstrates a weakness, falling in love with her cousin, Baron Wilhelm of Berlifitzing (played by Fonda's brother Peter, no less), whose family has always been enemies to the Metzengerstein family. He rejects her, however, due to her evil ways. Out of anger and vengeance, Frederique has her servants burn down Wilhelm's stables, but things do not go as planned, and Wilhelm dies, too, trying to save one of his horses. The next day a wild, black horse shows up at Frederique's castle. No one knows where it's from; not even Wilhelm's servants recognize it. The only one who can tame it is Frederique. Immediately it is clear that this horse is a reincarnation of Wilhelm.

Though a woman like Frederique would never admit to feelings of guilt, those feelings here are clearly observed once the horse arrives. She spends nearly every waking hour with him, and though she still engages in her adulterous pastimes, she does so detachedly. Frederique's guilt builds into the tale's finale, in which she contentedly escapes into an inexplicable place where she will no longer suffer her inability to requite her love with Wilhelm, the one thing in life she could never have.

Evocation of guilt is not the horse's only purpose, though. The horse comes to symbolize order - an order that Frederique apparently has longed for. With the arrival of the horse, Frederique becomes totally subdued, largely because she spends her every moment thinking of him; she gives up her chaotic propensities out of sheer infatuation. We must not forget that the horse was originally wild, too. Just as the beauty of the horse (and Wilhelm) reined in Frederique, Frederique's beauty reined in the horse.

The horse's symbolism is taken further with a subplot involving a tapestry. Just before the horse arrives, Frederique admires a tapestry of hers -- one which prominently features a wild, black horse. After the real horse's arrival, the tapestry horse vanishes, burned away apparently by a candle. Throughout the remainder of the film, a master tapestry artist attempts to repair the work, and Frederique anxiously awaits its completion. It is precisely when the tapestry is finished that Frederique runs away with the horse, never to return. The tapestry symbolizes chaos reined into order - a wild horse made still by beauty (as the horse exists within a still work of art) - and is therefore Frederique's symbol of a final imposition of such order upon the house of Metzengerstein. When she abandons the house, she leaves it to no one (as, presumably, her servants and guests will leave, too). It will remain in the ultimate state of order: stillness, non-use, death. When these restorations, of the tapestry and of order, have been completed, there is nothing more to be told and (in vintage Poe style once again) thus is the end of Frederique and Wilhelm.

Casting Fonda in the role of Frederique was the perfect decision by Vadim (though it probably didn't hurt that she was his wife at the time). Having Fonda, as beautiful as she is, consistently wear skimpy clothing creates a character that seethes sexuality - a sexuality that she fully embraces. Perhaps more importantly, these very aspects of her character also grant her great power. When she engages in sexual activity, her serious demeanor and her propensity to giving commands (such as instructing a partner not to hold her) make it clear that she cares only about her own desires and nothing of her partners'. Nevertheless, her partners, both male and female, are perfectly obliging, clearly won over by her sheer beauty.

"Metzengerstein" will, like Frederique herself, tantalize you, pull you in, and then horrify you. After all is finished, though, it leaves a world in which everything is rightly in its place. This is not just a story that evokes emotional response; it is a layered observation of the power of beauty and love to drain all vitality from even the most wild beings.

The next adaptation is "William Wilson," directed by Louis Malle. The title takes its name from the main character, who is even more sadistic than Frederique. It begins with Wilson pleading with a priest for time in a confession booth. He soon makes it known, though, that it is not absolution he is seeking but answers. He has done something that not even he can bear.

His story begins with a childhood incident at a boarding school. After being ratted out by a classmate, he has said classmate tied up and hung over a barrel of rats, methodically lowered into the barrel, raised, and lowered again. The torture session is interrupted, however, by a strange event: the arrival of a new student, who puts an end to the torture session by hitting Wilson with a snowball. The student's name: William Wilson (whom I'll refer to as "the doppelganger" for practical purposes).

This identically-named character shows up twice more in Wilson's life: once when Wilson is about to dissect a live woman and once when he is lashing a woman after beating her in poker (by cheating). Every time the doppelganger shows up, he puts a stop to Wilson's cruelty. Finally, Wilson decides he's had enough of the meddling. He challenges the doppelganger to a duel, loses, and, with his opponent's guard down, kills him with a dagger.

It is here that Wilson becomes so disturbed. While dying, the doppelganger says to Wilson, "You shouldn't have killed me. Without me you no longer exist. Dead to the world. Dead to hope," and Wilson immediately realizes what exactly the doppelganger was. Ever since his first appearance, the doppelganger served as Wilson's good side, his superego, always stopping him before he could take his malevolence to the extreme. When Wilson kills him, then, he kills whatever goodness there is within him, along with his only chance at any sort of redemption. The world no longer has any use for Wilson because, having killed his good side, he can never be anything but a miscreant. Even for someone as evil as him, this is a fate too great to bear.

The sheer relentlessness of Malle to depict scenarios of the utmost cruelty against the most helpless characters - a child, a naked woman, and a woman disgraced by being beaten at the game of which she prides herself a master - and Alain Delon's straight-faced portrayal of the title character combine to strengthen the disturbing nature of "William Wilson." The dissection scene, which consists of a woman tied to a table while Wilson circles her, scalpel in hand, half-explaining to his on-looking friends why he must remove her heart is unapologetically troubling, and the desperation on Delon's face when telling his story to the priest almost induces sympathy, even after we find out the things he has done. "William Wilson" is yet another disconcerting tale of misdeeds and guilt.

The third tale is "Toby Dammit," directed by Federico Fellini. It is a drastically loose adaptation of Poe's "Never Bet the Devil your Head" and is something of an oddity, though this is not surprising considering it is directed by Fellini. Until its final scene, "Toby Dammit" hardly even qualifies as horror. The story follows a fictitious famous actor, Toby Dammit, as he arrives in Rome for the filming of a movie. We are never shown the filming, however. Instead we get to see a question-and-answer television program with Dammit as the guest and then an award show at which the actor is honored.

The story focuses not on the events Dammit is involved in but on his very character and his outlook on the world. It seems this man cares nothing about his work, only about his celebrity. That is why we are not shown the filming of his movie; it wasn't of any importance to him. Instead we see him showing off his cool on the talk show and later enjoying his fame at the award show, at which he also becomes hopelessly drunk (which is only one or two degrees removed from how drunk he always seems to be).

In the end, apparently overcome with the emptiness and tedium of his life, Dammit has something of a breakdown while accepting his award. He flees in the Ferrari he was given for starring in the movie, half in an attempt to escape the award show and his life, and half in search of the Devil, who Dammit has convinced himself is a joyous young girl. It is here where the horror begins. Racing through the streets of Rome at night, Dammit encounters nothing but dead ends. He finally finds an open escape, a road on which stands the Devil. He attempts to reach her, and the inevitable happens: he loses his head. It is a sad, appropriate end for a man who treated his life as a meaningless playground.

The entire story feels like a dream. The camera, when presenting Dammit's point of view, often floats around, absorbing faces one-by-one, as if trying to figure out what they're doing in his life. The atmosphere is heavy as well. When Dammit arrives at the airport, the place is awash in fiery hues as if he were in Hell. At the award show, the darkness, wall-lessness, and fog pervading the scene make it feel as though experienced through a feverish haze. Throughout "Toby Dammit" is the distinct feeling that the world we are experiencing through Dammit's eyes is meaningless and bothersome.

Within every one of these films are the themes of depravity and death. These are characters that see no point in the world other than to use if for their own pleasure at whoever's expense that pleasure comes. While doing so, each coasts along carelessly with no thought of his or her own death. However, they all come to an eventual understanding of the emptiness of their lives, at which point they run from their pasts and inevitably tumble toward the death they once ignored. It is as if the desire for truth and order has brought a close to the stories of their lives.

Spirits of the Dead is a simultaneously unsettling and intriguing film. It is one that stands in awe of its characters despite the decadence of their moral codes. Ironically, in doing so it provides stories made inherently moral by their inevitable outcomes. Throughout the years there have been innumerable adaptations - many of them as loose as these - of Poe's work. These three riffs are among the best.

This review is part of our Shocktober Classics 2009: Staff Screams event.