Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

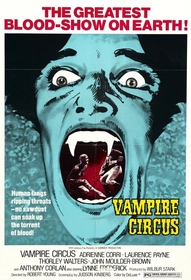

Vampire Circus (1972)

As the fortunes of Hammer Films began to dwindle in the early 1970s, they struggled to maintain relevance in the face of the shifting interests of their audiences. Their vampire movies were at the center of this struggle. While the existing Dracula series moved its setting to modern London with mixed results, another, more innovative approach emerged. These non-Dracula vampire movies emphasized new stories and characters while tweaking the standard vampire mythos. Robert Young's Vampire Circus (1972) is one of the films, one that remains a rich, complex horror film, although it suffers a few stumbles that stem from problems in production.

Fifteen years after the people of Schettel freed themselves from the influence of the vampire Count Mitterhaus (Robert Tayman), they find their village beset by plague and forcibly quarantined by the surrounding towns. Enter the Circus of Night, who promise “a thousand delights” to the beleaguered villagers. They have a clown, a strongman, acrobats, dancers, and their main act, Emil, a panther who seems to turn into a man. The timing of these gypsy performers appears to be perfect for lifting the spirits of Schettel. However, the Circus has another purpose beside entertainment – vengeance. Emil and the acrobats are vampires related to the Count, and they are here to enact his dying curse – to sacrifice the town's children in order to resurrect Mitterhaus.

As you can pretty easily discern from that synopsis, there's quite a bit going on in Vampire Circus. It's a film that's never content with “just” a vampire circus or a village beset by “silly” superstitions – it must be a vengeful vampire circus and a village with damned good reason for being afraid of the dark. Continuing the trend of complexity, the major thematic concern throughout Judson Kinberg's screenplay isn't one of clear-cut good vs. evil; instead, it's an examination of the inherent flaws in authoritarian structures at three levels – the familial, the aristocratic, and the communal.

The familial authoritarian unit is represented by the human families of Schettel. These are invariably dominated by a patriarch of some sort, one who reacts badly to any perceived threat to their power. Indeed, when the fathers of the village stake Mitterhaus and blow up his castle, the driving force does not appear to be the numerous murdered children, but that one of the men, Albert Mueller, has been cuckolded by the charismatic, virile Count. They are ridding themselves of the threat that Mitterhaus represents to their authority; whose wife will succumb to the vampire's animal magnetism next? It's telling that the men's victory celebration involves a mass whipping of Dora Mueller, the wayward wife. The act is performed with a fervor both ritualistic and sexual; it's hard to read the scene as anything but an analogy for gang rape. These heads of the family are both punishing Dora for her unfaithfulness and reclaiming their own sexual authority.

The irony is that these grasps at maintaining their power as the heads of their respective families bring nothing but misery to the whole village. Mitterhaus's dying words are a curse – that the town elders will die and their children with them (appropriate, of course, because a father's authority stems from having children). The beating of Dora Mueller provides her enough motivation to run off and seek the means of fulfilling that curse – The Circus of Night. Further, the utter destruction of Mitterhaus's castle – an overkill move informed more by testosterone than necessity – awakens a flock of bats who spread plague.

Even at a purely domestic level, the men seem unable to maintain the control they so eagerly sought; the burgomaster (Thorley Walters) is blissfully unaware that his teenage daughter is staying out late to get frisky with Emil. Another town elder watches in frustration as his wife flirts with the same vampire and later, his two boys sneak off to the circus despite being told to stay away. The only really functional human family is that of Dr. Kersh and his son, Anton. Their relationship is more analogous to that of a master and his apprentice rather than father and son. Kersh isn't interested in holding power over his son; instead, the two are united in a common goal of healing. By altering their dynamic from the authoritarian family unit to a more stable business relationship, the Kershes manage to survive.

Count Mitterhaus represents the failings of aristocratic authority. He enjoys the benefits of both his title (he lives in a huge castle and isolates himself from his constituency) and his own vampirism (he likes veal. Veal with pigtails). These “perks” are also the means to his destruction. In a way, Mitterhaus and his death speak to larger concerns in the evolution of the vampire film. Up until this point, the genre had been largely concerned with evil aristocrats terrorizing the peons by asserting their own superiority. In the first twelve minutes of Vampire Circus, we see why this approach fails. It turns out that those standard-issue Gothic castles are huge advertisements that tell angry torch-bearing mobs where the vampire lives. His isolation means there's only one easily subdued woman to try and stop said mob. And those nifty vampire powers come with less nifty vampire weaknesses, like susceptibility to having a stake driving through the chest, something which the men of Schettel are well-educated on. The message is clear; knowledge of vampire lore, both on the part of the villagers and the viewing audience, renders obsolete the vampire as aristocratic authority. Clearly, a new method of survival must be sought.

Initially, it seems that the members of the Circus of Night have found this method. They move from town to town as a nomadic group, vampires mixed in with their human familiars as near-equals.1 The Circus's mobility and communal bonds dispense with the now-exposed weaknesses in Count Mitterhaus's approach (and by extension, the approaches of most previous movie vampires). The circus performers are close-knit, act with a single purpose, and will commit any act in defense of the clan. We learn late in the film that the Circus has existed for a long time because they never stop long enough for anyone to figure out the danger they represent. They simply arrive, entertain, feed and leave. Wash, rinse, repeat. The Circus survives through teamwork; the circus performances earn money to meet the humans' needs and give the vampires access to an easy food supply. This interdependence is demonstrated in a sequence where the clown Michael (Skip Martin, The Masque of the Red Death) leads a family outside of the quarantine, accepts their payment, and then leaves them at the mercy of Emil in his panther form.2

Once the troupe takes on the task of avenging Count Mitterhaus, they take on a role of authority as a community, negating their practical survival plan and setting them on a path to ultimate failure. In order for the circus to carry out Mitterhaus's curse, they break from their successful hit-and-run routine and stay in Schettel for an extended period of time. This gives the villagers enough time to figure out who they are, what they are up to, and, most importantly, how to stop them. By the end of the movie, there isn't a single member of the circus left alive. By abandoning what had been a successful plan of survival in order to act as judge, jury, and executioner, they effectively seal their own doom.

With all of this complexity, it seems like Vampire Circus should be above petty narrative problems, but it isn't. I hate to say that, after the first half successfully establishes both the momentum and thematic concerns of the film, the second half drops the ball. The film lapses into a repetitive cycle of brandished crosses and magic mirrors. The vampires make no fewer than three attempts to kidnap the damsel-in-distress before their eventual success results in an intermittently exciting climactic battle. The loss of steam and depth can be traced to Hammer's decision to shut down production when director Robert Young went over the allotted six-week schedule. Consequently, some key scenes were never filmed, and Young was forced to edit around the omissions in post-production. It's one of those situations where what might have been overshadows what has actually come to pass.

For most films, an underdeveloped second half would be a serious concern, but it only dampens my recommendation of Vampire Circus a little. Watch it for the rich subtext and the multiple readings that can come from it (a quick poke around the Internet will reveal a number of different interpretations entirely different from my own). It really is Hammer doing some of its finest work.

What an interesting,

What an interesting, scholarly reading of the film. I think that, creatively, the appeal of Vampire Circus derives in no small measure from the very faults that make it so imperfect. While the first half is undoubtedly the more satisfying and accomplished (and possessed of a narrative sophistication that you nicely sum up here), the missing sequences in the second half are edited around with such inventive, creepy surrealism that I find myself forgiving so much of what is wrong with the end result. It's a highly flawed film. But my goodness it is interesting one too.

Have you seen 'Demons of the Mind'? It's a slightly lesser known Hammer film from the same period, and the two make useful companion pieces to each other. Both films share a certain similarity in terms of their experimental editing, ambition and playfulness with the (largely self-defined) rules of the Gothic genre. They are both extremely well produced, atmospheric messes. But Demons of the Mind is also irredeemably dull; a sin that, by no stretch of the imagination, one can accuse Vampire Circus of committing too.

It's funny actually, because

It's funny actually, because this review actually mimics the film in some ways. I had a lot more planned for it, but I had a deadline to meet (it was originally posted as part of our Reader's Choice event) and I eventually had to drop a bunch of points. But yes, a really great film that I highly enjoyed watching the multiple times required for writing this review.

I haven't seen Demons of the Mind yet, but I'll seek it out. Sounds like an interesting failure, which is one of my very favorite types of films to review.

"He went for a little walk! You should have seen his face!"

I'm guessing u saw the PG

I'm guessing u saw the PG American version. About 8 minutes or so were cut out to get the PG rating which also made the narrative more confusing. There IS an uncut version available from (I believe) Portugal. U can order it through Amazon. The print is in perfect shape---rich vivid colors, letterboxed and uncut. The original IS very violent and extreme but a big improvement over the PG version.

The twins were the highlight

The twins were the highlight of the film for me. What's more, for the time, the seduction of the two boys before their being bitten was quite edgy (I'm not sure it could be filmed in the US today). I've always thought that Vampire Circus may be the best of the non-Christopher Lee Hammer vampire flicks.

BTW: I have the DVD version from Portugal, which is very good. My understanding is that there is now a blu-ray version for sale.

I have the DVD from Portugal

I have the DVD from Portugal too. It is available here in the US in a DVD/Blu-Ray Combo Pack. It's uncut and the transfer is good but the Portugal one is just a little bit better:)