Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

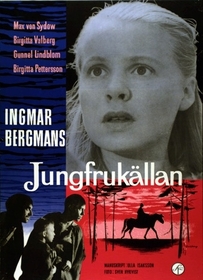

The Virgin Spring (1960)

"You are not alone Mareta, and God alone knows where the guilt lies."

So speaks Töre, a pious farmer questioning his faith in The Virgin Spring, the masterpiece morality tale by director Ingmar Bergman, who obviously has some questions for God himself. His film takes characters of complete innocence that are spiritually devout and forces them into situations of unadulterated evil, then questions the believability of a faith whose God would allow for such atrocities to occur. But Bergman isn't just questioning Christianity with his film; he's looking for answers from his audience. What he's putting on screen are scenarios that remain unfiltered; Bergman presents both scenes of rape and violent retribution without an opinion or without shying away from one or the other. He knows that both actions are reprehensible and that's the point. He leaves the audience with the gavel to decide the fates of his characters. Is the revenge that is sought (and had) in the film morally just because of the actions that come before it or are the characters that commit heinous crimes in the film all linked together as murderers of the same flock?

It is impossible not to speak about aspects of The Virgin Spring, especially its plot, without detailing a few scenes that are considered spoilers. So here is a warning: the remainder of this review will contain said spoilers. However, those readers that have seen the 1972 film The Last House on the Left will find a few eerie coincidences between the plot of that film and the plot of this one and will not find the plot as spoiled as though that have not seen either film; that's because director Wes Craven based his haunting tale off of Bergman's equally haunting one (Bergman and screenwriter Ulla Isaksson himself based his film off of a Swedish ballad called Töres dotter i Wänge, unseen by me).

Set in Sweden, The Virgin Spring takes place during a time where the belief in paganism was slowly waning while the rise of Christianity is evident. Karin (Birgitta Pettersson) is the chaste young daughter of two devout Christian farmers, Töre (Max von Sydow) and Märeta (Birgitta Valberg), and is asked to deliver candles to a local church, a task befitting only a virgin and pure spirit. This enrages Karin's sister, Ingeri (Gunnell Lindblom), a pregnant, raven-haired pagan who worships Odin, a Norse God, and secretly wishes harm upon her sister. Märeta feels the task is too dangerous for the simple-minded Karin and insists that Ingeri accompany her sister on her way to the church. After the two sisters set off, Ingeri separates and disappears into the woods, leaving Karin to her lonesome. She encounters three goat herders (two men and a young boy, all brothers) who attack her, rape her, and then kill her, leaving her in the woods but taking her clothes to sell in the town. It is when the herders show up at the home of Töre and Märeta looking for shelter (and to sell Karin's robes) that the parents are aware of their missing daughter's whereabouts and Töre invites them in for the night, secretly planning to exact revenge.

Much of the aforementioned scene between Karin and the three herders take place with minimal sound, sometimes complete silence. Bergman achieves a much higher sense of dread because of this silence, since he is leaving the audience to determine what sounds would be made. Just after one of the brothers comments on how attractive Karin is--how she has nice hands, a nice waist, and a nice neck-the dialogue mutes and the brothers begin to discuss their plans for the innocent girl. There's little doubt in the audience's mind what these men are saying and the fact that Bergman silences this portion of the conversation is chilling. A few seconds later, we don't need to know what was said, since the herders' actions speak in place of their silence. Because the audience has already replaced what they believe the herders to be saying, it makes the action seem much more intense, a heinous act coupled with the audience's worst fears.

Cinematographer Sven Nykvist, who would become a longtime collaborator with Bergman after this film, uses light and shadow to exquisite detail, providing the film with a powerful array of symbolism. For starters, he casts Karin in a bright light, causing an angelic glow to form around her. Since the film is shot in black-and-white, this glow causes Karin's hair to radiate in a white sheen, a color reserved for chastity. In contrast, the scenes involving Ingari are cast in shadow and her hair, though naturally dark already, appears almost black. Furthermore, there is a scene much later in the film where the three herders are having dinner with Töre and Märeta and while the scene's lighting is beaming on the two family members, the three brothers are cast in perpetual darkness, further creating a symbolic good versus evil motif in the film.

Nykvist and Bergman further this motif late in the film in a collaboration effort of expert scene setting and precise camerawork. As Töre is exacting his revenge on the three brothers for the murder of his daughter by stabbing one of them in the chest, Bergman positions his camera behind a fire that Nykvist has placed in the shot, so that the illusion is cast of both combatants falling into the flames. By his actions, Töre is condemning himself to hell and damnation. This idea is coupled with the next shot, which shows Töre rising up off the ground (which to the audience looks like he's rising up out of the fire thanks to Bergman's steady camera) and looking toward the youngest brother. Utilizing Nykvist's scene setting, Bergman is being frank about the actions that Töre has taken and how these actions would condemn one in the Christian faith. But since Töre is taking the lives of the men responsible for his daughter's deaths, does he deserve his sentence?

There is much nihilism to be found in The Virgin Spring and while none of it is truly just, Bergman suggests that because Töre is seeking revenge, God might forgive him somehow. After all, how else to explain the miracle that occurs at the end of the film after Töre has declared that he will build a church on the spot where his daughter died? In fact, is this a miracle at all or purely just a coincidence? It is curious that Bergman's film both ends and opens with similar instances. At the beginning of the film, Ingari is calling to her God Odin in hopes that he will cause harm to Karin. Now that we know Karin's fate in the film, is Ingari truly the one to blame here? As mentioned before, Bergman does not supply answers, just the scenes, and leaves his audience to either justify or condemn the questionable actions of the characters.

Speaking of Ingari, she is sadly overlooked in the film. She presents an interesting foil to Karin's pious and pure demeanor but as the film progresses, she does not evolve into much more. Take, for instance, her excursion into the woods as she separates from her sister. We're taken to a cabin (which has dead animals hanging from it, never a good sign) where Ingari speaks with a strange man. It is unclear to the audience the reason that Ingari winds up here or why she enters the man's house, but she does, and soon enough she finds herself running away. It is an ill-fitting scene that has no real bearing on the film, but raises a few eyebrows to be sure. After that we're back to Karin in the woods with the three herders, but what about Ingari? She is shown watching the atrocities that occur to her sister and she does nothing, although to be fair, she is probably frozen with fear. But later when she appears at the house after the three herders have been let inside, there is never a scene where Töre questions Ingari as to the whereabouts of his other daughter. Does Ingari ever explain herself to her father? Does she recognize the three brothers when they come to stay at her house? Does she even feel remorse for what has happened?

The Virgin Spring raises everything from eyebrows to pulses to questions about faith. This morality tale involves the audience at each turn, but never pauses to gather a consensus. Bergman is unequivocal about the actions that he shows on screen and purposely leaves his film with open-ended questions begging for discussion among his audience. Questions about faith and religion rarely get answered; they just pile atop one another. Bergman has started his audience along the path to finding those answers, but lets his viewers find their own way from there.

This review is part of our Shocktober Classics 2009: Staff Screams event.

"Jungfrukällan." Svenska Filminstitutet. Retrieved 09 October 2009.

Just thought I'd correct a

Ingari is not Karin's sister,

Ingari is not Karin's sister, as Karin's mother says a few times in the film that Karin is the only child she has left and also the older woman tells Ingari she is lucky to have been allowed to live with them and taken in.

The old man is certainly Odin and he tells Ingari that there are three dead men coming from the north - who turn out to be the men who kill Karin and are destined themselves to be killed.

The father invite anonymous

The father invite anonymous men to spend the night as a Christian act of charity. It seemed obvious to me he only figured out the murder AFTER his wife brings the bloodygarment. THEN he finds Ingari hiding under the stairs (in freezing weather no less.) As far as the miracle at the end, we don't really know for sure whethera spring pops out of the ground or if the creek has simply overflowed over a log or something.Either way the family seems to take it as a sign from Jehovah (certainly not from Odin.) Otherwise, your review is right on point.

Yes Andy, it is abundantly

Yes Andy, it is abundantly clear that the father knows nothing of the men's guilt until the wife shows him the evidence. And of course the family is Christian. The father feels a terrible guilt for killing the men (and the little boy who in fact is quite innocent as he is terrified by the other two and they have cut out his tongue). I feel so sorry for the child as he seemed to want to tell the family what happened and to ask them for protection. I found it the most tragic when he was thrown across the room and killed.

The father sees the miracle, in the opinion of himself and the family, of the water and decides to build a church there to prove his remorse as well as in remembrance of his daughter.

The film recalls a time when some Swedes were pagan while others were Christian, living in the same society.