Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

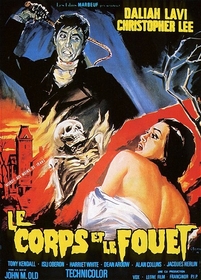

The Whip and the Body (1963)

It is impossible to simply watch Mario Bava’s The Whip and the Body. You can only hope to experience it, to let it wash over you and consume your senses. A sumptuous visual masterpiece dripping with sadomasochistic eroticism, The Whip and the Body is the most beautiful of all Bava’s films.

Prodigal son Kurt Menliff (Christopher Lee) returns to the family castle, ostensibly to congratulate his brother Christian (Tony Kendall) on his recent wedding to Nevenka (Daliah Lavi). However, Kurt’s true purpose reveals itself when he approaches Nevenka on the beach and renews their sadomasochistic relationship, whipping her across the back as she writhes in pain and pleasure. However, before this affair can be carried further, Kurt is stabbed and killed in his bedroom, the assailant unknown. Nevenka finds that Kurt will not stay dead. He appears to her at night, cracking his whip against her flesh and claiming her as his own. Is Nevenka going mad or is the ghost of her lover really tormenting her?

To get to the goods of The Whip and the Body, one must first work through the first twelve minutes, which are frustrating and vague. The relationships between the characters are not fully explicated, leading to confusion about their roles within the household. For instance, one character who is initially seen either associating with servants or performing servants’ duties is suddenly, off-handedly referred to as “cousin” by Kurt. The failure to establish this and other familial information has lead to a curious number of review texts referring to Nevenka as the former lover of Kurt’s father1, despite a complete lack of textual or subtextual evidence in favor of this supposition.

After these initial difficulties, The Whip and the Body roars forward with Kurt’s first lashing of Nevenka. The torrid sequence sets the stage for the rest of the film, not only in revealing the sexual proclivities that will be important to the plot, but also in the sheer eroticism of the moment. With each crack of the whip, Nevenka’s cries become less anguished and more ambiguous in pitch. While the audience may be unsure, Kurt sees her arousal clearly and comments on it. After the final assault, Nevenka’s brutalized body is heaving with wonton lust, which Kurt takes advantage of, kissing her passionately. Bava cuts to a shot of the whip that Kurt has tossed to the side, with the tide in the background, rising, falling, and rising again, a mirror of the lovers whom we can no longer see. The camera pans upward to Nevenka’s horse, a curious addition to the composition, but a deliberate one. In dream interpretation, horses can be symbols of sexuality, virility, and animalistic desire, all of which are definitely parts of the tryst occurring just a few yards from the edge of the frame.

For the first act of the film, Bava’s visuals are surprisingly restrained. Although his skillful use of shadow to frame and highlight his subjects is ever-present, he keeps his use of color understated (or understated for him, anyway). After Kurt’s murder, however, the look of The Whip and the Body slips into a strange, exhilarating kaleidoscope of twilight colors, alternating between accenting and being accented by pure blacks. The work done by Bava and cinematographer Ubaldo Terzano is impressive on a sheer technical level; the color and light seem like they’ve been masterfully painted in bold strokes across a three-dimensional canvas of darkness. The Whip and the Body is one of the few films of which I can think that can be admired with the sound and plot context removed, leaving only a series of moving images, each one more lovely and engrossing than the last.

Beyond being an enthralling visual experience, however, the look of The Whip and the Body has relevance to the plot as well. The transformation from natural to unnatural (or shall we say, supernatural) lighting is not arbitrary, but acts as a reflection of Nevenka’s mindset. The twilight colors represent ambivalence between day (rejection of Kurt and being a good wife) and night (love of Kurt and sexual ecstasy). Unable to cope with her conflicting feelings over her lover’s death, Nevenka’s outlook warps and the world becomes both beautiful and terrifying, filled with bright colors and sinister blackness. Since we see the isolated world of The Whip and the Body largely from Nevenka’s perspective, we can interpret the bizarre juxtapositions of light as proof of her madness. However, the strange look doesn’t cut out when we briefly follow Christian and other inhabitants of the castle, severely muddling the issue of Nevenka’s sanity. There are now two options – either Kurt’s evil really is infecting Menliff Castle, or the madness is spreading…

Bava came onto the production as a hired hand and didn’t take part in the writing process2, so it’s interesting that so much of the character work, especially in relation to Nevenka, is told purely through visuals. Ernesto Gastaldi’s script talks about violence and desire, but the camera and lighting (both Bava’s domain) unify them, showing pain as unquestionably pleasurable and true pleasure as requiring a healthy dose of pain. The most powerful example is the sequence that begins with a close-up of Nevenka’s face in the mirror as she fondles her own body. The camera pulls back to take in the full tableau, and Kurt’s face emerges from behind her, as if the darkness has been pulled off him like a sheet. She recoils and he peers at her, wordlessly, his half-shadowed face overpowering the frame. Even as Kurt circles around her, Bava keeps his head in the center of the shot, always taking up exactly the same amount of space, with Christopher Lee’s eyes exuding a powerful, animal sexuality. Nevenka threatens Kurt with a pair of scissors, claiming she doesn’t want him, but he plucks her pitiful weapon away and she slowly recedes to the bed. As Kurt begins to whip her, her back is bathed in purple light. Whether the light can be taken as a massive bruise or a massive hickey is inconsequential; they’re both contusions, one is given in violence and the other in passion. Kurt’s whipping of Nevenka is both violent and impassioned, blurring any distinctions into obscurity.

The sheer eroticism of The Whip and the Body is elusive and difficult to properly describe in words. The entanglement of pain and pleasure, color and darkness, desire and loathing, ghostly apparitions and insane hallucinations is so intense that not one of those elements is truly distinct from the other. They all rush together in Bava’s melting pot, where he creates a potent formula for raw sensuality that emanates from the screen and infects the audience. My co-editor, Julia Merriam, put it best during one scene: “Geez, even the doorknobs are sexual.”

Focusing all this carnality are the dual performances of Lee as Kurt and Lavi as Nevenka. Lee burns with a cold sexuality, which only appears to be a contradiction in terms until you see his performance. In his limited screen time, he gets to be callous and monstrous, but also romantic and even a little tragic. Lavi plays Nevenka like there’s a maelstrom brewing in her soul, propriety losing a war against animal desire. In one sequence, Christian finds Nevenka locked in Kurt’s tomb. As she is pulled out, she gasps for air, apparently out of fear and desperation. Moments later, however, her pelvis makes a sharp rise and fall as she finishes a moment of sexual bliss. Lavi’s performance may be slightly melodramatic, but it works as a means to communicate Nevenka’s inner turmoil. Sadly, different actors dub Kurt and Nevenka’s lines in the English-language version of The Whip and the Body. The actor filling in for Lee is a close if imperfect match, but Lavi’s replacement voice is pitched a full octave too high.

The Whip and the Body is a masterpiece for Mario Bava on two levels. In the first, it is a perfect visual realization and enhancement of the themes of violence, sexuality, and ambiguity in Gastaldi’s screenplay. Second, it is a work of beauty on its own, even with the soundtrack muted and the “pure” narrative removed, not unlike Hitchcock’s Vertigo (which is also a tale of obsession and revenant lovers when watched with the dialogue). The only reason it is not my favorite Bava film is that I simply cannot bring myself to choose one. Would that I suffered such problems with all directors.

This review is part of Mario Bava Week, the last of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

- Including Phil Hardy's "Overlook Encyclopedia of Horror" and Lawrence McCallum's "Italian Horror Films of the 1960s".

- Lucas, Tim. Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark. Video Watchdog, 2007. Pages 517 and 520.