Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

White Zombie (1932)

To comment on White Zombie is a task that daunts me. This minor classic, with its wealth of haunting imagery, has been commented on, criticized and analyzed by so many people, that I wonder what I can add.

Not that I haven't thought about the film. Stills from it ran in Famous Monsters of Filmland, the magazine that taught me respect for old horror films; those stills fed my imagination in those pre-cable, pre-home video days. As a kid, I was forever making my own mental movies out of photos seen in FM. White Zombie was no exception, but unlike other old horror films I wondered about and dreamed of, White Zombie did not disappoint my older self when I finally got to see it.

I first saw White Zombie in my twenties. My best friend and I were celebrating Halloween, and part of that celebration included screening at his apartment the public library's 16mm film print of the movie. Despite the print's splices, scratches, and soft sound, this screening of White Zombie planted indelible memories in my mind, strengthened further by seeing Roan's 2008 DVD release.

White Zombie is the story of Madeline Short (Madge Bellamy) and Neil Parker (John Harron), two young people engaged to be married, who are traveling in Haiti. Their host and friend Charles Beaumont (Robert W. Frazer) covets Madeline for himself. Beaumont seeks the assistance of the notorious -- and rather too-melodramatically named -- mill owner Murder Legendre (Bela Lugosi), who uses zombies to work his plantation. Legendre gives Beaumont a small container of a certain drug. Madeline seemingly dies from inhaling the drug and is entombed in a crypt. She is later removed from the crypt by Legendre and his zombie slaves. The empty grave is discovered by the devastated Neil, who enlists his friend Dr. Bruner to rescue Madeline from Legendre's grasp.

An independent production released in the summer of 1932, White Zombie was the first zombie film ever made. Unlike Universal's horror hits Dracula, Frankenstein (both 1931) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), it was not adapted from a literary source, though it drew some of its lore from journalist Wm. S. Seabrooks' 1929 book The Magic Island, the first book in English to describe Haitian voodoo practices. White Zombie may have drawn some elements from a play produced in New York and Chicago in February 1932, Zombie. (The writer, Kenneth S. Webb thought so -- he sued White Zombie's producers, Victor and Edward Halperin for infringement--but lost.)

White Zombie certainly displays influences from the horror films of Universal. Borrowing sets from Dracula and Frankenstein (among others), the film also stars Dracula's Bela Lugosi. Also like Dracula, White Zombie features a creepy carriage ride early in the film. (In this sequence the hero and heroine encounter Lugosi leading his zombies in a way that led me to think of a much later film -- Bergman's The Seventh Seal, with its famous image of Death leading a knight and his friends.) The central character of Lugosi's Murder Legendre certainly looks like a Universal baddie -- the makeup was designed and applied by Universal's makeup maven, Jack Pierce.

In turn, White Zombie influenced other films, defining the cinematic "rules" that more or less characterized movie depictions of zombies until George Romero's 1968 influential independent Night of the Living Dead was released. It also uses sound better than was common at the time, using music to create mood, an uncommon practice in the early years of talking pictures, and often startles the viewer with the use of the piercing cry of a vulture.

Like most independent productions of the time, the budget for White Zombie was small, and it shows in the casting choices. Excepting Lugosi, most of the players were silent film stars who careers had faded, and their performances are broad. Some major bloopers were left in, suggesting few takes being shot in the 11-day production. For example, one zombie, who is interestingly wearing an Iron Cross and a leg brace (suggesting a fallen WWI soldier), is clearly alive: his breath shows in the cold night air. (Hey, aren't these guys supposed to be in tropical Haiti and dead?) Another blooper is a shot of what is clearly a falcon being called a vulture. Finally, near the end, a comic blooper occurs when Lugosi's butler is tossed into a whirlpool by the zombies: actor Brandon Hurst holds his nose just as he's being tossed into the water!

Although the film is sometimes stagy, there is more camera movement than in Dracula, and one long scene in Dr. Bruner's study is done with no cuts, though the camera moves around; Hitchcock would likely have appreciated this experiment in technique.

The eyes and hands of characters get a lot of closeup time in the film. Frequently we see the close, disembodied eyes of Murder Legendre superimposed over the zombies as he influences them from afar -- reminiscent of the hypnotic powers of Dracula -- and his hands often clench together in a magical gesture when he makes the zombies carry out his will. (The first shot we see of Lugosi is his hand entering the frame.) We also see in closeup Madeline holding hands with Neil at their abortive wedding ceremony. This Expressionist-like use of visual syndoche substitutes the eyes for one's will and the hands for one's actions.

One scene in particular is Expressionistic: the scene in a nightclub where Neil broods over the loss of Madeline. We see no other patrons, just their shadows on the wall behind him. The eerie shadows emphasize how alone and powerless the character is.

It's no surprise that the film feels like a silent film at times. With its Expressionist touches, and the use of past-it silent film actors like Bellamy and Harron (whose mannerisms and flat line readings are ill-suited to sound film), White Zombie seemed somewhat old-fashioned even when it was new. But it compensates for this with a consistently somber mood, startling use of sound effects like the vulture's screams and the sound of the creaking mill that grinds up one of the zombies, and effective use of camera movement.

For a broadly acted, old-fashioned-even-then melodrama, there are some interesting ambiguities. The film suggests that some zombies are reanimated dead (one is shot several times with no ill effect.) But the hero's missionary friend Dr. Bruner, the "Van Helsing" of the story, says that the zombies are not; the heroine, zombified by a potion given her by Legendre, turns out in the end to be made into a zombie only temporarily.

There is moral ambiguity as well, some of it presented through old-fashioned costume choices: the thoroughly evil Legendre, the not-entirely-rotten Charles Beaumont, and the good Dr. Bruner are all seen at some point in the film wearing black hats and overcoats, suggesting that evil deeds tempt every one. More interestingly, the "good" Dr. Bruner attempts to murder the evil Murder by hiding and stabbing him from behind--clearly a morally ambiguous act even in a tale of this type.

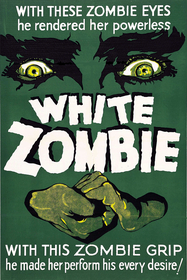

The Roan restoration features commentary by Gary Don Rhodes, a noted film historian and author of White Zombie: A Critical Look at the Film and a History of Its Production. Rhodes says in the commentary that he does not believe that the word "white" in the title refers only to the virginal state of the unambiguously good character of Madeline Short -- as opposed to, say, "scarlet" -- and is not meant to denote race. This is somewhat difficult to accept, given the White Zombie film poster has this text: SHE WAS NOT ALIVE... NOR DEAD... Just a WHITE ZOMBIE Performing his every desire! This strongly hints at the dehumanizing practice of "white slavery, " a now-outmoded term referring to "enforced prostitution," according to Merriam-Webster's. Although someone of any race could be forced into prostitution, "white" was used to distinguish the practice from the legal enslavement of black people. Also, given that zombies were then defined only as black Haitian victims of voodoo (or properly, "voudon") and race-conscious titles like White Savage were being made by Hollywood as late as the mid-forties, it becomes impossible to think White Zombie doesn't play on multiple meanings of the word "white."

White Zombie is neither a classic of the stature of the Universal Gothic horrors of the 1930s, nor a dragging potboiler with ham-fisted acting, these being two extreme critical opinions of this once-forgotten movie. It resides in film history somewhere in the middle, being an atmospheric, influential film with a fine performance by Bela Lugosi. Every horror fan and cinephile should see this film, preferably with the lights out.

Primary Source:

Rhodes, Gary Don. Audio Commentary. White Zombie. DVD. Roan Group Archival Entertainment, 1999.

Thanks to Max Cheney for the guest review. Be sure to drop by Max's blog, The Drunken Severed Head.

I believe that White Zombie

I believe that White Zombie is one of the great unheralded horror classics of the 1930's, and unfortunately, it is almost forgotten today, overrun by the modern flesh eating creatures that cloud the true history of zombie lore. While I would really never like to see this remade, it may fare better that the some of the modern tales that have been re-done!

I first found out about this

I first found out about this movie on video and was pleasantly surprised by its quality and its sense of atmosphere. Give me an old classic like "White Zombie" over any of the CGI malarkey they're passing off onto us any day. Which reminds me, why is it that the zombies in the movies like "I Am Legend" and "28 Days Later" are so less scarier than the ones that came out in 1932? Hasn't there been any progress at all? Maybe Val Lewton should come back to haunt the lot of them.

A Minor Classic! To me,

A Minor Classic! To me, the atmosphere and beauty of horror films from this era, is far more interesting than the soulless CGI-laden movies of today. Just look at the clips from the new Wolfman--fakey and laughable! They spend millions of dollars and still can't get it right. Give me the low-budget, handmade classics anyday.

I remember the images of this

I remember the images of this from FMF as well and how Forrey respectfully handled the rcomments about some classics. But I simply have never seen the film for fear I would not like it and have my 'own mental' movie images shattered. But after this excellent review I am going to go find it right now and give it a go.

Bill @ The Uranium Cafe

As I've said over on our

As I've said over on our boards...

Though I always liked that title for a movie, I always thought it was a bit misleading for that particular movie. WHITE VOODOO or VOODOO MASTER would have been a much better title I think. Since Lugosi seems to not just make zombie slaves, but also manifest other aspects of voodoo by bending Madeline's will to his own by chemical, hypnotic and telepathic means.

I also discovered this film on the pages of FM and viewed it while I was in Jr. High or maybe a Freshman in HS, via the 16mm print at the local library. Those were the days, eh Max? I think this was one of the first 16mm prints I sought out for purchase in The Big Reel. I don't think it was ever a forgotten film, but it sure was a well kept secret next to the Universal monster titles. Still, I think it stands shoulder to shoulder with MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE any day.

It really is a shame that the heritage of these much creepier Zombies have been obscured by the Romero variety. One of my pet peeves to be sure. I think it was some of the uninformed public that first began calling Romero's "Ungodly Creatures" zombies though. Romero shyed away from calling them Zombies also for a long time. The Z word was actually never used once in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, and I was still referring to them as "Living Dead" or "Flesh eating Ghouls" into the 1980's. Other than one small passing reference tucked in the middle of the action of the biker invasion sequence (which I think was an ad-lib by Foree) the word "Zombie" didn't turn up in DAWN OF THE DEAD either.

On CGI: Before CGI film makers just had to be more inventive, especally those in the lower buget houses. They had to work with the limitations of the medium, which when successful really showed who had a command of their craft. Today's film makers in the Horror genre seem to mostly be coming out of the music video arena... And none have developed their craft to the point they should even be given a feature to direct. Talented film makers have learned the rule should always be that CGI is "A" tool that can be used to help tell your story, not "THE ONLY" tool to be used.

SID TERROR

Editor-In-Chief

TheHorrorDrunx.com Online Magazine

Victor Halperin also directed

Update: I have found a decent copy of " Revolt of the Zombies " over at the Internet archive. It's a 2 gig download but the Archive servers will upload it to you at 250+ kb. Yes it is in public domain.