Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

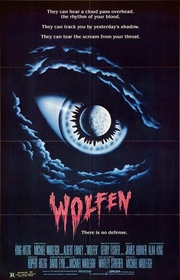

Wolfen (1981)

Horror films have been melded with almost every genre imaginable, but Wolfen must be the first socio-political werewolf movie.

Yes, there are bloodthirsty wolves. But there's also points to be made about man's mistreatment of nature and the American Indians, the deterioration of the inner city and the burgeoning greed of 1980s corporate America, all wrapped up in a murder mystery involving New York City police captain Albert Finney.

Directed and co-written by Michael Wadleigh, Wolfen remains the noted Woodstock documentarian's only narrative feature (though he did serve as cinematographer on Martin Scorsese's first film, Who's That Knocking at My Door?). Based on a novel by "The Hunger" author Whitley Strieber, Wolfen opens with rich land developer Christopher VanderVeer heading home from a ground breaking party to turn the slums of the Bronx into an uppity playground for the New York City elite. Along with his coke-snorting wife and voodoo-practicing bodyguard, VanderVeer is viciously torn apart by unseen creatures while stopping in Battery Park.

The gaping wounds on the victims contain no traces of metal, and the only clue found is hair that appears to belong to an endangered species of wolves no longer found in New York. When a construction crew digs up a collection of derelict body parts, the same hair is found, leaving Finney, with the help of coroner Gregory Hines and criminal psychologist Diane Venora, to figure out the connection.

The investigation eventually leads the trio to Native American ex-militant Edward James Olmos and subsequently the legend of a pack of wolves who, driven underground by man, prey upon the bungled and the botched in the slums of America's metropolises.

Though director Wadleigh provides tension and some good gore (particularly a stylish, fire-consumed beheading towards the end), his mistake is making the wolves sympathetic figures, forced to kill society's left-overs to survive against the horrible, oppressive American way of life. Which might have worked if the wolves had stuck to offing homeless drug-addicts and elitist businessmen, but when they start chowing down on some of the film's more likable protagonist it makes them a little harder to root for.

The film's jaunty narrative, rumored to be the work of hacks in Warner Brother's editing room, fails to explain vital parts of the story. Finney's shaky past (he's supposedly returning from a self-imposed retirement) is never unturned. He simply comes back to work, with the only explanation being "He had some family troubles and started to drink a little too much." Here's a news flash: Finney still drinks too much, and someone sure as hell needs to explain why.

The presence of Venora seems to serve only one purpose: So Finney has someone to have sex with. A noted stage actress appearing in her first film, Venora does her best but the randomness of her appearances make it obvious that she fell victim to the studio editing scissors.

Wolfen's attempts at black humor also fail miserably, detracting from an otherwise solid turn from Hines as he spits out one-liners that diffuse tension without generating laughs.

Helping overcome the flaws are Gerry Fisher's innovative photography and a cast that is a notch above the usual genre fare. Fisher fills the screen with varying points of view, including the wolves' distorted heat-vision (similar to John McTiernan alien-vision from 1987's Predator), while Finney underplays well and adds a bit of class to the sometimes overindulgent material. Always good for a bizarre character turn, Tom Noonan (a taller, pastier version of Michael J. Pollard) also pops up as a loony wolf expert.

But in the end, Wolfen's ambition is far greater than the final result. Had it been released any other year, the film might be more fondly remembered. However, it hit theaters during the werewolf renaissance led by Joe Dante's The Howling and John Landis' An American Werewolf in London. Compared to these classics, Wolfen suffers. Judged on its own merits, it's a well-intentioned but uneven lycanthropic amalgam of horror and social commentary that will, at least, provoke more thought than most of the genre's movies.