Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

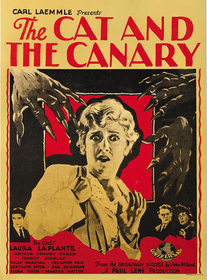

The Cat and the Canary (1927)

The opening credits roll. The audience sees a man immersed in a fortress of oversized medicine bottles, presumably on the brink of madness. An image of a cat is superimposed to the right of the screen. The man? He’s the canary awaiting slaughter. Most would assume that this scene could only be created by modern movie technology. In fact, it is the opening scene from the 1927 version of The Cat and the Canary, a film that catapulted silent films from sheer entertainment to art form.

The Cat and the Canary, originally a stage play, weaves a tale now very familiar to lovers of the horror genre. Cyrus West, a millionaire, died a presumed madman. His will is only to be read 20 years following his death. The heir? A 20-something girl by the name of Annabelle West. However, the will has an odd condition – since the greed of West’s family drove him to madness (like cats surrounding a canary), Annabelle must be deemed psychologically sound, or the money turns over to a secret heir named in an envelope held by Mr. Crosby, the lawyer overseeing the will reading. Mr. Crosby soon goes missing, with Annabelle the only witness to his disappearance. Is Annabelle spiraling into insanity? Or is the mystery heir pushing her there? The film takes us on a twisty whodunit, one of the very first of the genre, and indubitably one of the few that withstand the test of time.

The viewer must respect the ambition of the film, especially as it was filmed when moviemaking was in its infancy. Many early films (both silent and talkies – this film was released a month before the first talkie film) bumble along inconsistently, as filmmakers were still experimenting with story pacing and cinematography techniques with this still-new media. The Cat and the Canary, on the other hand, looks as if the filmmakers already benefited from some of the greatest writers and directors of the future classic horror genre and used these techniques to make this film. This credit to this goes to the director, Paul Leni, a expressionist who had a cinematographic eye well ahead of his time. For example, many stage play movie adaptations fall into the trap of looking like “a stage play taped for the big screen” with minimal emphasis on the environment and plenty of stageplay overacting (a downfall of even much later classics, such as A Streetcar Named Desire). Likewise, silent films fall victim to overacting and overly emphasized body movements, which often turn dramatic scenes into sheer comedy. The Cat and the Canary does not have either of these flaws. Instead, Leni took it to the far other side of the spectrum, embracing subtlety and realism, making it one of the best-acted silent films of its time.

Should Paul Leni be living today, he would clearly be considered an arthouse director simply due to his visual acuity. Many silent films rely too heavily on the text cards, making the visual images far less effective. The Cat and the Canary does the opposite by telling the story almost exclusively through images with minimal assistance of text. For example, for the opening scene, Leni could easily have simply shown a madman with an ample amount of text delineating his back story. Instead, he tells the opening completely visually using symbols to get his point across, with no benefit of text. This is far more effective because it allows the audience to get jump into the mind of the madman. The audience understands Cyrus West’s entrapment in the gallows of his brain when we see him immersed helplessly in the fortress of oversized medicine bottles. We understand the greed of his relatives, when a superimposed snarling cat appears next to West in the corner of the screen. And we understand the importance of his life by the care taken in revealing his will. These opening images resonate feelings deep inside the audience members, and we become emotionally invested in the film immediately – far more so, than if the drama unfolding was frequently interrupted by text.

Leni also understood the importance of the audience’s subconscious investment in the film, which he proved by the use of subtle psychotropic images during turning points of the film. A floating skull when death is mentioned flashes in the corner for a second-- gone before we register it was there. A hand reaches for Annabelle while she is sleeping, however we only see the shadow over her nightgown (indicating that said hand may be a figment of Annabelle’s, and our own, imagination.) And finally, there is an absolutely inspiring shot of Annabelle sitting in a large dining room chair while the camera pans between the bars of the back of the chair giving the audience the feeling that Annabelle is trapped in a cage. It is shots like these, so advanced for their time that puts this film in the same league as the silent barrier-breakers Metropolis and The Phantom of the Opera.

The story of The Cat and the Canary became the stepping-stone of modern day dramedies. Until this point, most films fell into a distinct genre, be it Nosferatu or Charlie Chaplin. The Cat and the Canary is one of the first films to successfully blend genres as it is equally a comedy, love story, and drama. This film holds its delicate balance between multiple genres perfectly, a balance that has not been matched given its two inferior remakes (one in 1939 with Bob Hope who turned it into a lukewarm comedy, and again in 1979, an uninspiring trainwreck which has become the scourge of fans of the original). Laura La Plante brings some moments of comic relief to the table in her role as a stir-crazy, easily startled heiress. Creighton Hale sublimely plays his role as a bubbling oaf with eyes set on Annabelle. On the other side of the spectrum, Tully Marshall -- clearly one of the best actors of his time -- gives a Grim Reaper outlook to his role as Mr. Crosby.

With these talented actors’ contributions, The Cat and the Canary never blows a single scene. The moments of suspense are terrifiying, the comedy scenes are uproarious, and the love scenes between Annabelle and Paul are unequivocally flawless. Most love scenes in silent films are hokey and excruciating to watch (mostly due to overacting and overly emphasized body movements). The love scene in this film tells its tale exclusively through non-verbal cues, allowing the viewer to read between the lines, which makes it perhaps the most touching celluloid moment from this time period.

The Cat and the Canary achieves everything it sets out to achieve. That alone does not make it remarkable. But in achieving its goals, it overcomes the barriers of silent filmmaking so completely and so effortlessly that it becomes a prime specimen of not only silent filmmaking, but every stage play adaptation, every future dramedy, and genre-spanning films in general. Instead of becoming another theater adaptation, it became a blueprint for what makes classics “classics.” It’s about time you indulged.