Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

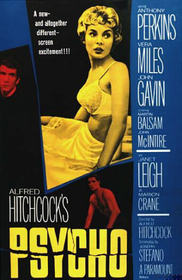

Psycho (1960)

Writing a review lauding the merits of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho is like writing an essay on why breathing is important. Or better yet, why sex feels good. Talk about begging the question. Anyone who watches Psycho brings his or her own insights, cinematic IQ, prejudices, fears, and collective memories into the interpretation. And like any classic film, Psycho resonates with new meaning every time one watches it. Perceptions change, interpretations mutate, and assumptions evolve. If one goal of a good film review is to recreate the experience of watching the film, then reviewing Psycho is the equivalent of reveling in cinematic ecstasy. So beware, here comes the swoon.

And I forewarn readers now: Psycho is one of the most important movies I have ever seen. Thus, my obvious bias. Hitchcock's masterpiece introduced me to three important cinematic realities. The first was Hitchcock himself and his many volumes of classic films. The second was the power of the director as auteur. And the third was that, at an early age, I realized how great movies operate on two levels. The first level is built upon their entertainment value, which lurks on the surface, dazzles viewers' eyes, and evokes visceral emotions that both comfort and disturb. The other resides in their aesthetic value, which lurks far below the surface and builds upon layers of complexities that can, when crafted wisely, intellectually overwhelm the viewer. Like so many of Hitchcock's films, Psycho operates on both of these levels with profound skill.

Yet as often as I have viewed this film, the less I seem to understand it. Sure, the plot is simple enough. But that second layer is so rich and intimidating (How many books and articles have been written about this film?) that every time I view it I at one point become so entranced by the story's twists and turns that I abandon my reviewer's cap and forget to actually analyze anything. In fact, I would argue the film defies analysis. Investigations into the film often leave one feeling embarrassed, humbled, and empty at the film's conclusion, like the target of a brilliant man's joke. It is no coincidence Hitchcock considered Psycho to be his "little joke." Perhaps more than any other movie in film history, Psycho reveals the brooding power directors have over their audiences.

In Phoenix, Arizona, Janet Leigh plays Marion Crane, a secretary having an affair with a hunk named Sam Loomis (a name John Carpenter later used for Donald Pleasence's character in Halloween). Crane wants more from their relationship, but they depart without resolving their future. Crane returns to her job in a real estate office and encounters a sexist cowboy buying a home for his soon-to-be-wed daughter. She eventually pockets the $40,000 used for this transaction and leaves with it to marry Loomis, but her boss notices her at a traffic light in the city after she asked him for the afternoon off due to a headache. This awkward moment triggers her paranoia, and she flees to California.

During her odyssey, she is stopped by a police officer that suspects something unusual about her. Languishing in guilt and confusion, she later exchanges her car at a used car lot and settles for the evening in the infamous Bates Hotel, where she encounters the even more infamous Norman Bates, played by Anthony Perkins in one of the seminal performances in Hollywood history. There she is murdered midway through the film in arguably the most analyzed scene in film history: the provocative "shower scene." An investigation unfolds after Crane's death that is conducted by a detective, Milton Arbogast, who is hired by her former boss to retrieve the $40,000. Eventually, the detective is murdered as well. Crane's sister, Lila, and Loomis resume the search for the missing Crane. What they unearth is a complex web of murders emanating within the Bates household full of psychoanalytical angst, Oedipal tension, and shattered identities.

One of the unique qualities of Psycho is that the violence of the narrative is also perpetrated on the viewer. The fact that Crane's murder occurs halfway through the film is a powerful and innovative narrative tool that assaults the viewer's expectations about protagonists. Quite simply, they are not supposed to die halfway through the movie! Of course, this aspect of the film is part of what makes the legendary shower scene so tragic. Viewed alone, the scene is powerful, but for some, it may not live up to its hype. But viewed in the context of the film's organic whole, the scene is intensely shocking. The first half of the film is partially designed to lure the viewer into identifying with Crane. Hitchcock admitted this twist was one of the central points of interest he identified with in Robert Bloch's pulp novel of the same name, which served as the story's original source. Bloch is given writing credits along with Joseph Stefano, who wrote the screenplay.

In fact, Hitchcock took some chances with this story. He purchased the rights to Bloch's novel for $9,000, but Paramount execs grunted when they learned of his project and refused to support it. Nevertheless, the astute Hitchcock made a deal with them: he would fund the film himself by using inexpensive Universal facilities and would waive his standard director's fee of approximately $250,000 per film. In return, he would own 60% of the negatives. The director used several craftsmen from his famous television show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, to make the film, which ultimately cost him $800,000 to produce.

The brilliance of Hitchcock was his ability to combine aesthetic skill with commercial success. His films are full of artistic and technical innovations, yet he, unlike his peers venturing into the cinematic vanguard, also found commercial success. Subsequently, Hitchcock constantly had an eye on the business side of movies, and he was keenly aware of the growing popularity of B-movie horror/monster films emerging in the 1950s. Hitchcock wanted to tap into this market, but he also wanted to do so with an original statement.

The creation of Norman Bates, a kind, reserved, mama's boy-like man who seemingly couldn't hurt a fly, was a startling new monster. Sure, Bates wasn't the first cinematic psychopath (Robert Mitchum in Night of the Hunter immediately comes to mind). But after Norman Bates, monsters rapidly morphed into real humans. They were no longer exotic "others" such as vampires, werewolves, or aliens from outer space; they were normal people on the surface bubbling with psychotic cancers underneath and capable of horrific violence.

In many ways, Psycho laid the groundwork for the modern slasher film. It established the victim as a daring, sexy female who in many ways threatens the patriarchal status quo. Crane sleeps with a married man, steals from a real estate company, escapes the police, and comforts a creepy male loner. The film also defined the slasher as a young, confused male full of psychological trauma. Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees are direct descendants of Norman Bates. The film also stamped the genre with another notable trend: the killer's only motivation is psychological. The randomness in which these killers murder can only be understood through a psychoanalytical lens.

However, as seminal as Psycho is, its brilliance is amplified when compared to its progeny. Psycho has yet to be effectively duplicated, because it cannot be duplicated; its formula can only be loosely followed. Even Gus Van Sant's 1998 remake, which was doomed from the start, is nothing more than a deliberate scene-by-scene recreation. Yet although Psycho laid a blueprint that has been emulated in varying degrees ever since, Hitchcock's original formula for slasher films is still hauntingly original. The protagonist is killed halfway through the film; the villain is a transvestite; the film is shot in black and white (although the director had abandoned that formula several films ago); a cagey and successful detective is quickly killed (don't the smart ones usually survive?); the film is shot in what is essentially two sets: the Bates hotel and the Bates estate; and the slasher is actually apprehended and imprisoned.

But perhaps the most provocative aspect of Psycho's originality is the fact that the film virtually dismisses the notion of domesticity. The only footage of a "home" that we see is the Bates estate, but their "home" is as dysfunctional as they come. There is no anchor or base for the characters; they all are drifters roaming the "outside" seeking answers to some kind of unspoken mystery. Crane is seeking a real relationship with Loomis, or money, or some kind of escape from her pedestrian role as a secretary; Loomis is seeking romance, lust, or an escape from his dying marriage; Norman is, well, Norman, seeking something far too complex to capture here; etc. The movie suggests that the traditional American "home" is seething with emptiness, vacant, and occupied by something altogether different, an impersonal, rented space devoid of tradition and stuffed, like the birds in Norman's office, with materials used to satisfy personal needs and egos. This lack of a base disorients viewers further and makes them even more uncomfortable.

Although the film abandons traditional portrayals of the stereotypical American home, a place where privacy is usually found in abundance, Hitchcock uses Psycho to construct an exposition on other definitions of privacy. Most of the film is a prolonged intrusion on the personal space of the characters and the viewer. As the camera constantly invades their personal space, our personal space as viewers is also penetrated. On one hand, Hitchcock frames places from high-angles or long-distance panoramic shots to highlight the privacy they offer, yet he shatters this intimacy by slowly poking the camera into those very private spaces. The early scenes of Phoenix are a perfect example. We move from an aerial shot of the city to a slow vertical pan into the window of a couple sharing an adulterous moment.

Conversely, our personal comfort zone is frequently mocked by Hitchcock's various surprises. For example, the police officer that haunts Crane during her desert odyssey clearly senses trouble, but he never officially acts on it. The choke shots of his face clearly present him as a menacing authoritarian figure, but his actions pale in comparison to what one expects of him. He rather lightly lets Crane off in the desert, and he is even more impotent during the car sale.

Another example of how Hitchcock raids our expectations occurs when Bates sinks the car containing Crane's corpse. As the wetlands slowly engulf the car, the timing of this submersion is important. At first, we might think, "Nobody is going to notice?" But then the speed and efficiency in which it sinks convinces us. As soon as we feel comfortable again, the submersion stops. "Now what," we think, only to have the car resume its descent. The point here is that Hitchcock almost sadistically takes great pleasure in invading our consciousness as a film viewer. He keeps reminding us that he is in charge, not Bates, Crane, Loomis, or Arbogast, yet he does so with such an alluring deceptiveness that we cannot help but be seduced.

The shower scene truly functions as the film's climax, yet it also marks the conclusion of Story 1 and the beginning of Story 2. The shock of that scene resonates throughout the rest of the film. The scene also reminds us how invasive that camera can be: it has penetrated the most intimate of areas - a shower, where a beautiful woman is bathing. The scene required almost 70 camera angles and took one week to shoot. Ironically, the scene was shot toward the end of the film's production, and by this time, Perkins had already left the set for a Broadway gig. Thus, a stand-in played the role of the slasher.

Bernard Hermann's score is equally mesmerizing. The screeching violins that sound like fingernails scratching a chalkboard echo throughout Psycho and are arguably one of the most noticeable compositions in film history. Hermann, who may own one of the most impressive resumes in Hollywood history with films such as Citizen Kane, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Cape Fear, and Taxi Driver to his credit, worked frequently with Hitchcock, and by the time Psycho appeared, they had already collaborated on five films. Simply stated, Psycho is not Psycho without Hermann's haunting notes, which are as shocking and suspenseful as any of the visual depictions.

Finally, another of Psycho's many contributions was that it essentially hammered the nails in the coffin of Hollywood's notorious Production Code. Films like Some Like It Hot may have purchased the coffin, nails, and hammer, but Psycho did the actual slamming. The shower scene alone dismantled at least three tenets of the Code: the visual depiction of blood, footage of a naked woman (did she have to be taking a shower?), and actual footage of a woman being stabbed repeatedly. The opening scenes of Crane wearing lingerie and sleeping with a married man certainly didn't help celebrate the Code's at times rigid and at other times absurd parameters.

When Psycho was first released, reactions were mixed. Audiences wanted to see a "Hitchcock film," with its lavish sets and colorful, complex vistas, but some were turned off by what they saw because Psycho clearly deviated from its maker's standard formulas. After all, the master of suspense's previous hits included North by Northwest, Vertigo, To Catch a Thief, and Rear Window. In this context, Psycho was radically different. Nevertheless, the film earned $15 million in its first year alone, which immediately became his most successful film to date.

And then there is Janet Leigh's performance. And Anthony Perkins's. And the editing. And the wonderful set design of the Bates Motel and adjoining house. The list goes on. My definition of a great film is simple: the film may not be the best in any one category (directing, acting, sound, etc.), but it certainly ranks very high in every category. Psycho is perhaps the greatest example of this definition.

Trivia:

The infamous shower scene has 90 edits in it. Anthony Perkins was in New York at the time doing a play, so a double was used in his place.

Hitchcock used Bosco chocolate syrup for blood.

In one of the only publicity stunts enforcable by law, nobody was allowed into the film after it had begun.

I agree with the review. This

I agree with the review. This film is amazing, but for me this is not Hitch's best nor even most important horror/slasher outing; that honour goes to the delicious "Frenzy". Underseen and underappreciated, "Frenzy" shook me up and changed me more than Psycho ever did. Check it out.

I saw this film in NYC many

I saw this film in NYC many years ago on a date. I cannot remember anything about the person, but I vividly rember screaming at the shower murder scene. A truly memorable and exciting film.

Frenzy is a great film too,

Frenzy is a great film too, but it came several years after Psycho, and Hitchcock was in a very different place. Nevertheless, it would be fun to compare and contrast the two.

---Chris Justice

I actually think this is

I actually think this is Hitchcock´s weakest movies, thanks to Joseph Stefano´s script. I still feel sympathy for poor Norman, more ill than evil - precisely opposite seems to be true with American psycho´s filthy sadistic perv Patrick Bateman, who was named after him.

I don't like this at

I don't like this at all...but that's cause of censorship. I first saw it on TV late at night when I was about 7. My dad stayed up to watch it with me. Despite the fact that it was on late at night the shower scene AND Arbogast's murder were cut out! Even worse the explanation at the end was edited rendering it incomprehesible. Since then I have seen it uncut---but first impressions are hard to shake.

Whilst the Gus Van Sant 1998

Whilst the Gus Van Sant 1998 version of Hitchcock's 1960 film Psycho is almost a shot for shot remake, there has always been some taboo surrounding the the newer version. Arguably the remake is extremely poor and evidently scores 4.6/10 where as the original scores 8.7/10. What is it about the remake that makes it less aesthetically pleasing and such a disliked film, even though it is almost a exact reproduction?

My guess is because van Sant

My guess is because van Sant dared to remake a movie that is considered a classic. Also, as u said, it's almost a shot by shot remake of the original which is kind of pointless. van Sant adds nothing to it at all.

Why Van Sant's version is

Why Van Sant's version is disliked? A big reason is because the performances are Atrocious! It's hard to decide who gives the worst performance: Anne Heche or Vince Vaughn. There's just no comparison with the original actors Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins. Despite all the talk about it being a "shot-by-shot" remake, there are plenty of places where it deviates. Right of the bat, the first scene after the credits is staged differently than the original. Then there are all those pointless inserts during the murder scenes.