Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

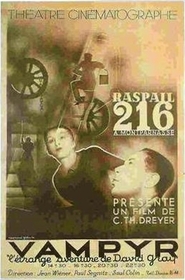

Vampyr (1932)

Carl Theodor Dreyer's experimental Vampyr is an exercise in audacity. Watching certain scenes in the film reminds one of shorts produced in university film classes that are full of daring, cunning, and innovation. However, unlike most of those novice films, a man many consider to be one of Europe's most underrated "great directors" directed Vampyr. Dreyer, who is most popular for The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927), often hailed as one of the greatest silent films ever produced, once said he wanted to create a visual daydream to demonstrate the psychological dimensions of horror. He definitely succeeded.

Loosely based on J. Sheridan Le Fanu's popular lesbian vampire story Carmilla (1872), which is about a young girl seduced by a strange female acquaintance, the film was a commercial failure when it was released in 1932 and ultimately ruined Dreyer's production company. The director did not return to cinema until a decade later because he suffered a nervous breakdown after Vampyr's release. The unusual nature of the film resides in virtually every aspect of its creation. The film was shot in a Paris castle, and the actors were mostly amateurs Dreyer recruited from the streets of Paris. Julien West, the producer and a Dutch aristocrat who financed the film, is the protagonist; the doctor, Jan Hieronimko, was a Polish journalist; and Rena Mandel, who plays Gisele, was a French model. The only established cast member was Sybille Schmitz, who plays Leone in the film.

The film introduces viewers to David Gray, the protagonist, who checks into a strange inn for the evening. He is a curious student of occult studies, and during his first evening there, a mysterious man surprisingly enters his room and utters two cryptic warnings: "she must not die" and "to be opened after my death". The latter is in reference to a package left in Gray's room. Naturally, Gray's curiosity is aroused, so he investigates the inn and its grounds. He finds a surreal cast of characters there and a series of unusual rooms. After several more bizarre discoveries, Gray learns that the mysterious man, who lives in a nearby chateau, was shot, so he assists him and meets the man's family. He encounters an old man whose daughter is sick with an unusual ailment. Gray later decides to open the package and discovers a book about vampires. He begins having hallucinatory dreams, one of his own death, and he eventually learns that a vampire, whose identity will surprise some, is at the heart of the inn's spookiness. Gray then, like the hero of any good vampire flick, seeks to destroy the beast.

One of the first qualities of the film that immediately stands out is the claustrophobic feel Dreyer creates with an unusual set design and camera work. As Gray cautiously meanders through the inn, one feels as if the walls are literally going to crash on his head, an effect amplified by Dreyer's low-angle shots. His room feels unusually small, and the hallways, based on their sheer size alone, appear uncomfortable. All of this effectively exacerbates the weirdness the inhabitants of those halls and rooms convey.

The surreal quality of the film is legendary and rooted in its unique cinematography. One legend claims that Dreyer and his cinematographer Rudolf Maté achieved their daydream-like, milky effects by shooting during the dawn hours. Another suggests that Maté used a wad of gauze over the lens to replicate the effect of some overexposed film he accidentally produced. Another claims that light accidentally leaked into the camera during shooting, a device they decided to continue throughout most of the film. The subjective, moving camera establishes interesting points of view that culminate in Gray's carriage ride in a coffin. Here we experience the inside of a coffin in a manner yet to be duplicated in film history. Throughout other portions of the film, the camera's frequent pans, tilts, and dolly movements allow it to break through the hypnotic aura Dreyer creates. The camera is never left frozen; it might be the only entity in the film that escapes Dreyer's trance-like work. Yet when the camera follows Gray, it does so in a manner that captures his sleepwalking-like reverie. This creates an interesting contrast. The periodical shots of the fluctuating skies and the obsessive focus on religious iconography are equally effective. Gray's faded silhouette, which strangely becomes his living character, is also surreal. Finally, the delayed and reverse-action shadows remind the viewer that this is a setting where the physical laws of the universe no longer apply.

Dreyer's work was at the crossroads of major cinematic schools emerging throughout Europe in the 1920s and 30s. His work is an excellent synthesis of German, Soviet, and French aesthetic trends. His rapidly cut montages are a direct descendant of Russian directors such as Dovzhenko, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin. Throughout the film, as Gray seeks to unravel the mystery before his eyes, Dreyer establishes montages through images of an angelic weather vane, cloud movements, or mesmerizing shadows digging a grave. These montages create a psychological tension by alluding to implicit clues in the narrative. However, explicitly, our search for clues is trapped in Gray's obsessively voyeuristic point of view.

Furthermore, his frequent use of shadows and chaotic, oblique lines are a direct tribute to the German expressionists of the 1920s and 30s. During Gray's journeys into the darker recesses of the inn, Dreyer creates a confusing labyrinthine effect replete with shadows and dense compositions layered with illogically placed objects such as pendulums, dancers, an orchestra, and flourmills. He also pays tribute to Buñuel and the French Surrealists of the 20s and 30s by making the entire film an exercise in absurd drama. The disconnected montages, unusual plot twists, and experimental cinematography make this film an exotic endeavor that clashes with genre-anchored expectations. The relationship between cause and effect is suspended, so the real horror emerges from the incongruence one feels while watching this film. Dreyer excels in alienating the viewer through technique, and although the film does contain sound, it resonates more like a silent film, especially since sound's introduction into cinema was in its nascent stages in the early 30s. In fact, the film was originally shot as a silent film with occasional voices dubbed in post-production. Subsequently, the sound disorients the viewer further because it refuses to pigeonhole the film into a category of film. "Isn't this a silent film?" one asks. No, because nothing is what it seems. There are sounds, they just rarely come from the on-screen voices that we expect.

And throughout the film, Gray wanders as if led by some alluring spirit. But the essence of that spirit is questionable. His passion for the occult complicates his motives because it is unclear if he genuinely wants to solve the grave occurrences he finds or simply feels compelled to study the vampire as a scientific inquiry. One wonders if he has benevolent motives or has simply found another possible topic for a book chapter. As an academic, he reeks of an aloof, professorial air, one that is too detached in theory to actually resolve anything. Yet he continues to look, to search, and to peek around every corner. His desire for knowledge and an explanation is unusual for someone so enamored with supernatural happenings. Yet this contradiction makes him an appealing character. The duality of his character adds a depth to his personality that Dreyer's cinematography, so focused on atmospherics and mood, at times seems to abandon.

Vampyr was released in the United States in 1948 with the new title Castle of Doom, but sadly, the film has not been restored and its print versions are weak. Unfortunately, the only remaining print of the film is in desperate need of a facelift. Too often, defects, stains, or graininess in the print distract the viewer, almost as much as the excessive intertitles, which convey the feeling that you are at times reading a book instead of watching a film.

And however impressive this film is, Vampyr is by no means for everyone, especially certain types of horror aficionados. If you want action, gore, and visual blood orgies, this film is not for you. If you want a clear narrative full of shocking and explicit twists and turns, this film is not for you. I'm sure some will not even consider it scary. Not even remotely scary. But if you let Dreyer guide your fears instead of the plot or characters, you might be surprised at how shocking Vampyr truly is.