Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

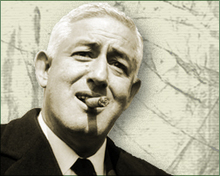

William Castle

After a 1927 performance of the Broadway stage production of Dracula, gangly William Schloss boldly bluffed his way backstage with little more than swagger and an insistence that the star of the show, Bela Lugosi, was expecting him. Lugosi was not, but he invited to watch future performances from backstage. This ploy to meet a star may have been the first major step the young entrepreneur later known as William Castle took as a showman, but it would be no means be his last. When Dracula went on tour, the boy was invited to join as the assistant stage manager at Lugosi’s suggestion.

On the tour, Castle suggested several workable promotion gimmicks such as placing a closed black coffin outside of the theater. He also suggested having Dracula disappear from the stage in a puff of smoke to reappear in the audience scaring the people out of their wits then vanish and reappear on stage. William Castle was developing a true talent for showmanship.

He continued getting jobs after the tour as a stage manager. With the coming of the Great Depression, he was forced to find work in other areas, feeling all the while that he was moving too far from his goals of working in the theater. Then in spring of 1939, he made a deal with Orson Welles to rent his theater in Stony Creek, Connecticut, which Welles was intending to close in order to go to Hollywood and make motion pictures. The deal was for ten weeks at $500.00 a week, which he paid for with a part of his inheritance from his father.

Castle had the difficult task of selling tickets for a theater that had just lost its main attraction. When Actors Equity wouldn’t let him use prominent German actress Ellen Schwanneke – they had rules against foreign actors taking work that could go to Americans – he claimed he had discovered a German play with a leading female role that could only go to a German. The play, Das Ist Nicht der Kinder (Not for Children), was a fabrication, and Castle ended up writing the thing over a weekend. Later, when Schwanneke was invited to return to Nazi-run Germany to perform, Castle used the incident to generate headlines by sending her refusal direct to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, then leaking the information to the press. He even trashed his own theater to make it appear that Fascist sympathizers had vandalized it (an action which he later said he regretted). The result was phenomenal press coverage and excellent box office.

The production drew the attention of Samuel Marks, emissary of Columbia Pictures and the great mogul Harry Cohn. Marks invited Castle to come to Hollywood, saying he had the stuff to work for Harry Cohn. The door to motion pictures was now open.

However, when he met with Cohn, Castle quickly learned that he was not going to bluff his way to the top this time. Cohn was known for being a straight shooter with a low tolerance for bull. As president of Columbia, he made friends and enemies and was equally hard on producers, directors, and actors alike. Castle worked his way up through the ranks, learning the craft of filmmaking as a dialogue director, assistant editor, and bit player. He was finally granted the chance to direct a feature in 1943, with the Boston Blackie mystery Chance of a Lifetime (1943).

Castle churned out crime dramas and mysteries for Columbia for six years. He distinguished himself with a bonafide hit, When Strangers Marry (1944), when on loan to Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures. In the late 1940s, his contract was sold to Universal-International for a three-year tenure, where he added westerns to his genre repertoire.

Soon after his contract with Universal expired, Castle met again with Harry Cohn, who lured him back to Columbia with promises of more money and projects. He continued to work with his usual genres, but he also helmed costume dramas like Serpent of the Nile and Slaves of Babylon (both 1953).

After seeing Henri-Georges Clouzot's classic chiller Diabolique, Castle realized that he too wanted to scare audiences. In search of a story, he found “The Marble Forest,” a novel that suited his ideal. The story followed a small town doctor whose daughter was kidnapped by a madman and buried alive in an unknown grave at an unnamed cemetery. It had horror, red herring suspects and a surprise ending -- everything a boy could want. Securing the rights, he worked with writer Robb White to adapt the book for a film version, retitling the story Macabre. Not only did Castle direct the film, but he also produced it – something he would do with all of his subsequent films. To boost public interest, Castle took out an insurance policy with Lloyds of London for anyone who would die of fright (providing they did not have a previously known heart condition) while watching the movie. Macabre was a smash hit and a new chapter in Castle’s career began.

Castle next looked to the old dark house scenario for his next horror film, House on Haunted Hill. The producer/director cast Vincent Price, who he had met by chance in coffee shop, in the lead. This time the marketing gimmick, a twelve-foot tall skeleton that flew over the audience on an overhead cable, had a name – “Emergo.” The box office had a name for the film itself – “a hit”.

Tricks like “Emergo” made the theater experience a special event for audiences, something that Castle recognized and continued to exploit. For The Tingler (1959, also starring Price), he developed “Percepto”, where random theater seats wired with a minor electrical shock that went off during the film’s climax. 13 Ghosts (1960) boasted “Illusion-O”, which allowed audiences to view the film’s specters through a special lens, just like the characters in the film. Theater crowds could even vote for whether the title villain of Mr. Sardonicus (1962) would be punished or shown mercy (in actuality, no “mercy” ending was filmed).

Even as he turned out one hit after the other, Castle kept his eye on market trends. Seeing that Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) was taking in big money, he started making psychological thrillers like Homicidal (1961), Strait-Jacket (1964), and I Saw What You Did (1965). He also kept things light with comedies like Zotz (1962) and The Old Dark House (1962), a co-production with Britain’s Hammer Films that remade the 1932 classic of the same name.

Castle’s most successful film, however, was one he only produced – Rosemary’s Baby. He ceded the director’s chair – at production studio Paramount’s request – to the up-and-coming Polish director Roman Polanski.

Although Rosemary's Baby was a smash hit, it had an adverse affect on Castle himself. He received threatening letters, many anonymous, that accused the producer of "bringing the devil to the country". Others stated things like, "you'll die for what you've done" and "I hope you rot in Hell." Around the same time, Castle took ill with uremic poisoning. He became delusional and thought that the curses of the hate mail may have been working.

After surgery and treatments and a long convalescence, Castle went back to work, producing (1972’s “Ghost Story” television series, 1975’s Bug) and directing (1974’s Shanks). However, on May 31, 1977, William Castle died of a heart attack, leaving a legacy of thrills, chills, and some of the zaniest marketing ideas in film history.

Revised by Nate Yapp, 03/2008.

Sources:

Castle, William. Step Right Up! I'm Gonna Scare the Pants Off America. Putnam, 1976.

Smith, Richard Harland. "William Castle Profile". Turner Classic Movies. Publication date unknown. Retrieved 24 March 2008. <http://www.tcm.com/thismonth/article/?cid=179087&mainArticleId=179085>

Waite, Ron. "The William Castle Story". Horror-wood Webzine. Published February 2003. Retrieved 24 March 2008. <http://www.horror-wood.com/castle.htm>