Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

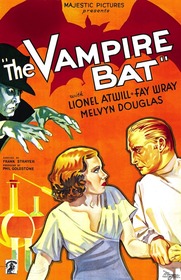

The Vampire Bat (1933)

Genre is cumulative. Successful elements of one film are picked up, refined, and tweaked by the next. Sometimes the result is an improvement or even an advancement, other times it is imitation or homage. In many cases, a film will combine the perceived successes of its predecessors, synthesizing them into something familiar but new. These are the places where genre evolves. Take the case of The Vampire Bat, which borrows two of the stars of Doctor X and Mystery of the Wax Museum, but more importantly, it carries forward some of the themes and genre trappings of Universal's 1931 horror hits, Dracula and Frankenstein. In doing so, the film shows some innovation of its own, resulting in an entertaining, if occasionally slipshod film.

The Vampire Bat has very little to do with the title animals. Certainly there is an infestation of bats in the village of Kleinschloss, but the townspeople are more concerned with actual vampires. One can scarcely blame them -- people keep turning up dead, drained of blood, with two puncture wounds in their neck. Investigator Karl Brettschneider (Melvyn Douglas) knows that there must be a rational explanation for the killings. With the help of his girlfriend, Ruth (Fay Wray), and her employer, eminent scientist Dr. Otto von Niemann (Lionel Atwill), Karl soon comes to believe that the truth may be more fantastic than he could have possibly anticipated.

Given the popularity of both Dracula and Frankenstein, it was only a matter of time before some film came along that tried to marry elements from both. The Vampire Bat is just that movie. Beyond the obvious use of vampire lore, The Vampire Bat's debt to Dracula also extends to its use of a Van Helsing style vampire expert in the form of Doctor Von Niemann, some wide-eyed hypnosis, and a tendency to run exposition through very talky drawing room conversations. From Frankenstein, there's the middle European setting (using the same backlot sets, no less), mobs of villagers with torches, and, later in the film, some science fiction elements.

Solidifying The Vampire Bat's relationship to both films is Dwight Frye (Renfield in Dracula and Fritz in Frankenstein), featured as Herman, a simple-minded man suspected of being the town vampire. Frye is often positioned in a way that recalls one of the two films. For instance, there is the shot Herman peers through a gate in a manner very similar to the opening scene of Frankenstein. Herman also has an obsession with bats and blood, which harkens back to Frye's role as Renfield.

However, all of that is window dressing. The most interesting result of the combination of elements from Dracula and Frankenstein is the conflict between reason and superstition. While this was a minor element in Dracula and had a slightly larger presence in Frankenstein (couched more as science vs. religion), here it is a constant tension underlying everything. The people of Kleinschloss "know" there is a vampire among them. No amount of reason or evidence to the contrary will dissuade them, and every tiny bit of proof that confirms their already held beliefs is seized upon and clung to. As one villager says after yet another local is murdered, "Kringen said Herman (the suspected vampire) would get him and he did." Never mind that there's no proof that Herman was anywhere near the scene of the crime. In the minds of the villagers, the fulfillment of one part of the prediction proves the whole of it.

Navigating through the village's superstitious waters is Karl, who is visually set apart from them by his metropolitan dress style. His nicer clothes and intelligent speech set him as the voice of reason, a rare thing in Kleinschloss. However, Karl's status as the reasonable one is a feint by the filmmakers -- eventually, with some prodding from Niemann, he comes around to the idea that vampires may be real. In fact, The Vampire Bat may be the first example of a particular kind of horror plot that exemplifies the tension between reason and superstition, one that would be repeated in several Hammer vampire films in the 1960s and 1970s. In this plot, the one reasonable man surrounded by superstitious common folk learns, often with the help of a wise expert, that his rationality means nothing in the face of an actual supernatural threat. This basic outline is still being used today; it appears in a somewhat modified form in this year's The Woman in Black.

The Vampire Bat pulls out a surprise twist on its own formula in the third act (spoilers for The Vampire Bat will be prevalent from this point on in the review). After our hero has begun to pursue the possibility that a vampire is at work, the expert he has relied on, Dr. Niemann, is revealed to be the actual villain. There are no supernatural forces at work -- Niemann is a regular mad scientist, bent on creating new life (more shades of Frankenstein). The tissue he's developed in the lab needs blood, so he's hypnotized his lab assistant, Emil, to kidnap townspeople so he can steal theirs. As it turns out, Karl was correct from the start -- the explanations for the murders was rational. Well, rational within the world of the film, anyway.

The reveal also turns what had been a plot weakness into a strength. The idea of a logical-minded scientist like Dr. Niemann supporting a theory as fantastic as vampires seems odd. However, knowing his role in the murders, it makes sense that he would try to direct the investigation away from himself by feeding the local superstition. On review, his tactics are delightfully insidious. Karl has rejected the villagers' tales of monsters, partially because they seem so unreasonable. Niemann uses his veneer of respectable rationality to good effect, peppering his tales of bloodsucking ghouls with phrases like "according to accepted theory", adding authority where no real authority exists. Once one is aware of the twist, rewatching Atwill's act as a master manipulator is a real joy. Unfortunately, while the twist is of great retroactive benefit, it also ruins the character for the rest of the film. Once all cards are on the table, Niemann becomes another monologuing madman who leers at pretty girls before tying them up. His motivations also seem pretty thin for a fellow as intelligent as he's been revealed to be.

Poor Herman fares much worse than Niemann, however, being poorly written and (I hate to say this of any Dwight Frye performance) acted throughout all of his scenes. Herman's clearly meant to be analogous to Dracula's Renfield, but instead of being mad, he's mentally challenged. To show his cognitive dysfunction, Herman speaks in an improbably inconsistent syntax. Within a single scene, he'll refer to himself as "Herman", "I", or "me". Frye doesn't deliver the garbled sentences with any sort of authenticity and the words hang in the air like dissonant musical notes.

Behind the camera, director Frank R. Strayer is about as uneven as Herman's speech patterns. He opens the movie with a creepy series of shots that culminate in a chilling scream. It's the perfect mood-setter, but the mood dissipates with the static, overly talky exposition scenes that follow. The rest of the film follows this basic pattern. When Strayer is working on macabre visuals, he's absolutely aces, doing some of the best work of the era. However, these sequences are few and far between. Whenever characters have to talk, and they often do, the scenes are stagey and plodding. Since Strayer had started out in the silent era, one wonders if he was simply more comfortable doing complex visual work without sound, since he is clearly capable of great visuals. Whatever the reason, it remains disappointing that Strayer's talent is only apparent in limited doses in The Vampire Bat.

In combining elements of Dracula and Frankenstein, The Vampire Bat puts forth its own lasting advancements in the horror genre. Future films then take what The Vampire Bat does and twist it into new and different configurations. On and on this process goes, each film flowing into the next over the course of the 20th century and into the 21st. When we watch modern horror films, we know that some part of their DNA comes from renowned classics like Dracula, Frankenstein, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Psycho, and Night of the Living Dead, yes. But there is also genetic material from the little films, the scrappy unsung independent films like The Vampire Bat, that took from the greats and then refined what they took and made it better or at least different. They weren't always great films, but they are no less important to the history of horror films. And after all, isn't that what we're here to celebrate?

I personally thought Herman

I personally thought Herman was one of Dwight's best performances, but that's just me.

Why no mention of the actual

Why no mention of the actual monster?

good atmosphere flick but the 'monster' was just rediculous lol

I'm struggling to remember an

I'm struggling to remember an actual monster in this movie. I guess the hypnotized lab assistant? The vampire bats of the title were regular-size bats and red herrings to boot.

"He went for a little walk! You should have seen his face!"