Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

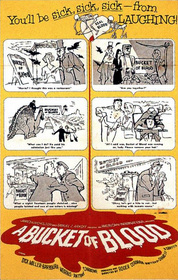

A Bucket of Blood (1959)

Watching the first moments of A Bucket of Blood, viewers might be confused as to whether they should laugh at it or with it. The film starts at a beat club where a pompous hipster named Maxwell is reciting awful poetry that is actually more like dramatic soapbox ranting. “I will talk to you of art. For there is nothing else to talk about. For there is nothing else,” he says. Go ahead and laugh with no guilt, though, because it is soon becomes impossible for the film not to realize its own humor, even though it never accentuates it. A Bucket of Blood does not take many risks, but it is a fun horror flick about bad artists and worse art.

The main character of the movie is Walter Paisley (Dick Miller), a loner busboy who reveres Maxwell and aspires to become a sculptor. Poor Walter has the heart for it, but he just doesn’t have the brains or talent to rise in the art culture (or probably any other culture, for that matter). He sits at home trying to mold clay, pleading, “Come on, be a nose. Be a nose!” While trying to free his landlady’s cat from the apartment wall one night, he accidentally stabs it with a knife, killing it immediately. In a desperate attempt to be accepted as an artist, he covers the knife-imbedded cat in clay and passes it off as a sculpture fully created by him. Immediately, Walter is exalted by the regulars at the club and is encouraged to produce more. Then, oops, another unfortunate incident occurs involving an impulsive reaction to a threatening police officer. He covers this dead body in clay, too, and calls it “Murdered Man.” After this second “creation,” Walter is showered with the approval he has always craved, and he secretly begins a homicidal life in the pursuit of art.

Director Roger Corman is clearly having fun by putting ridiculous artists up on screen. The film’s most basic example of this is a supporting character: Maxwell, a pompous “poet” who works by simply saying the most confusing things he can think of, like “Life is an obscure hobo bumming a ride on the omnibus of art.” At one point, he even claims that if some don’t understand his art, they are simply not “aware.” He acts exactly like those obnoxious dilettante poets who inhabit amateur poetry night at our local coffee shops. It also helps that his pretentious eccentricity is portrayed so frankly. Actor Julian Burton brings the character so truly to life as a wannabe beat poet that he always seems to take himself perfectly seriously — a task which must have been hard given such ridiculous lines. Also, the humor of this failed artist is not exaggerated or highlighted to force laughs out of us. Instead of being surrounded by superior characters that cue the viewer to scoff at him, Maxwell is constantly with friends and admirers who take him as seriously as he takes himself. This makes our laughing much more meaningful; we laugh at him because we know he sucks. It’s as if Corman’s goal was to bring viewers together in the collective ridicule of horrible art. Sign me up!

If Maxwell is a basic example of a false artist, then Walter is the extreme version of the same thing. As Maxwell’s art is metaphorically dead on the inside (there’s nothing beneath its façade of seemingly profound phrases), Walter’s art is literally dead on the inside. When he gains recognition, he becomes even more of an absurd character than Maxwell. This is quite an accomplishment, and he does it by acting and dressing much more stereotypically “beat,” ordering cappuccinos, wearing a beret and glasses, and smoking through a cigarette holder. Just as Walter’s sculptures merely appear to be art, Walter outwardly tries to pass himself off as having become “truly” beat. In actuality, he was much closer to authentic beat-ness beforehand, wearing jeans and a simple black sweater due to his modest income. It is obvious that Walter was more truly himself before he began passing off the products of his accidents and transgressions as art.

The film doesn’t stop at the mockery of bad art though. It also takes a few jabs at the admirers of such junk. When Walter shows his clay-embalmed man with a split-open head to unknowing beatniks, for example, they attempt to show off their own insight by discussing its portrayal of the self-pity of modern man. Their attempts to sound sophisticated are belied by the viewer’s knowledge that the “art” that they are lauding is nothing more than manslaughter covered in clay. No one who has any part in the perpetuation of crappy art is safe from the film’s mockery.

If we don’t immediately know whether Corman is laughing at his characters, it is because he trusts that we are smart enough to know when to laugh on our own. That is important because for a film whose sole merit lies in its belittling of bad art, the laughs have to be genuine in order for the derision to effectively occur (we’re deriding it by laughing). Haters of bad art unite! A Bucket of Blood is here to bring us together.

This review is part of Roger Corman Week, the first of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

Dick Miller has been such an

Dick Miller has been such an accomplished scene stealer that it's a real pleasure to see him carry a film written especially for him."The Little Shop of Horrors" was also written for him.