Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

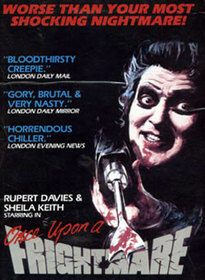

Frightmare (1974)

Pete Walker's Frightmare appears to have been made primarily to shock the common British public of 1974; in many ways, it's nothing more than series of grotesqueries strung along a thin thread of plot. Thirty-four years later, however, its power to achieve its primary goal has diminished significantly. The ever-increasing desensitization of movie audience puts a movie like Frightmare at significant risk of obsolescence. Thankfully, Frightmare is buoyed by a delightful morbid streak, as well as a command performance by actress Sheila Keith. Although time has sapped the film's intended horror, it's not a bad little flick to put on when you need to darken an abominably cheery day.

In 1957, Dorothy and Edmund Yates (Keith and Rupert Davies) were committed to an institution for the criminally insane, she for acts of murder and cannibalism and he for covering up her crimes. Fifteen years later, they are pronounced fit for society and released. However, in Dorothy's case the doctors may have jumped the gun a bit. Edmund and eldest daughter, Jackie (Deborah Fairfax), try to discover just how far Mother's bloodlust has taken her. Meanwhile, youngest daughter Debbie (Kim Butcher) begins to explore the crazy roots of her family tree as fully as possible.

The inescapable fact of Frightmare is that it's a commercial product, constructed to put as many butts in theater seats as possible.The calculated pursuit of cash is most apparent in the film's treatment of cannibalism, a subject that was only really beginning to make the rounds in cinema in the early 1970s. (Between 20-25 films dealing with cannibalism were made in the five-year period between 1970 and 1974 – roughly as many as had been produced in the entire history of cinema previous). Pete Walker himself concedes that the inclusion of this angle is purely mercenary. When the moderator on Frightmare's DVD commentary seeks some deeper thought process behind the film's cannibalism plot, the director shrugs off the suggestion: “It started off as a contrivance ... how are we going to shock them next?”1 The film deals with the topic on the most superficial of levels – there is more talk of flesh-eating than there is visual evidence of it, and no real thematic conclusions can be drawn from it (whereas in most cannibalism films, there's a bevy of possible readings attached to the consumption of humans by humans). If anything, it's an excuse to mangle the victims with a power drill after they've already snuffed it.

Of course, there's nothing inherently wrong in putting the box office first – a lot of very good horror has been made by people with images of balanced ledgers running through their heads. The pursuit of profit is hardly anathema to art. While Walker and screenwriter David McGillivray miss the thematic possibilities of cannibalism, it is partially because they are more concerned with authority and its failures. In particular, Frightmare displays an overwhelming distrust of psychiatry and related professions. After Dorothy was declared sane and released from Lansdowne Hospital, the doctors considered her case a closed matter. No effort was made to follow-up and ensure she was adjusting properly, because in their eyes, her declaration of sanity was unconditional and, by virtue of its very declaration, incontrovertible. Of course, events show their diagnosis to be rather premature. The second example of the failures of mental health care appears in the form of Graham (Paul Greenwood), a psychiatrist who is dating Jackie. He attempts to reach out to Debbie, in an attempt to treat the motivation behind her delinquency, but he's blind to the reality of the situation (a fact that is alluded to by the character's large, thick-rimmed glasses). Like the doctors who released Dorothy back into society, Graham is convinced that a good regimen of talking it out is all that is needed to cure someone who appears pathologically incapable of sanity.

There is something at once refreshing and disappointing about Pete Walker's direction. He is almost completely without pretense – you'll almost never find him using stylistic choices to batter the viewer over the head with themes. He is concerned with moving the plot when it needs moving along and shocking the audience when they need a shock. He is particularly skilled with the latter, able to milk each moment for everything its worth without coming off as gratuitous. There's a great scene when Dorothy is attending to a corpse she has stuffed under some hay in a barn. She uses a power drill on the head (for no good reason I can discern), which spits back a healthy spatter of blood across her face as she grins maniacally. Walker clearly enjoys creating moments like this (and there are many similarly ghastly bits throughout the film) and that translates into delight for the audience, perhaps more than there should be.

However, Walker's functional approach doesn't leave a lot of room for much outside of his immediate goal, which is where the disappointment comes in. It seems as if he approaches each shot as an end unto itself, rather than as a larger part of the whole. One wishes that the director would have made a little more effort to create a cohesive cinematic product rather than a collection of connected scenes. Many of the plot sequences, especially those not involving Dorothy or Edmund, are dry and talky. They never seem to foreshadow, except when the script absolutely calls for it. By contrast, the moments of horror seem to remove characters from their personalities; Dorothy often switches from a semi-tragic victim of madness to an evil, savage monster when she's called on to do something grisly.

This last point is a real shame, because it undercuts what is otherwise a marvelous performance from Sheila Keith. Keith's Dorothy is the is the epitome of the passive-aggressive mother – vacillating between strong and weak, smart and feeble-minded, attentive and disoriented as the situation demands. Keith always makes it clear to the audience that above all else, it is her character's manipulative side that is in control, and that all other emotions are a mask, a deception. In one scene, she is able to present a bewildered, senile old woman to combat Jackie's accusations of a relapse and then, mere minutes later, wolfishly ask an awful favor that she posits as completely harmless. The kind of skill with which Keith imbues her portrayal makes it clear why Walker used her in his films more than any other actor.

Frightmare is not a great film, but then again, it was never intended to be. Pete Walker intended to shock his audience and I'd put money down that he did -- when the film came out. Today, the film stands as a survivor, overcoming its dated reliance on the gore tolerance of 1974 British audiences and emerging as a macabre, though not entirely successful, bit of fun.

1 Walker, Pete, Peter Jessop, and Steven Chibnall. Commentary. Frightmare. 1974. The Pete Walker Collection: Frightmare. Media Blasters, 2006.

I loved this wee gem of a 70s

I loved this wee gem of a 70s horror.