Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

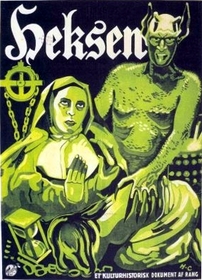

Häxan (1922)

Häxan: Witchcraft through the Ages, Danish director Benjamin Christensen’s silent documentary on the history of witchcraft, is reputed as the strangest silent film ever made, if not the strangest of all films. His point (at the start, anyway) is to show us that witchcraft never really existed and that the things people thought were witchcraft, primarily in the fifteenth century, were actually everyday incidents blown out of proportion. As it proceeds, the argument becomes progressively incoherent, but what the film lacks in substance, it more than makes up for in style. Häxan easily lives up to its reputation and remains shocking even today.

This style-over-substance characteristic catches us off-guard because the film’s beginning is dryly educational. Christensen shows us medieval woodcuttings depicting the cosmological order of the world. Via title cards between these woodcuttings, he lectures us on how they also illustrate naive understandings of witchcraft, which is to say that they depict witchcraft as existing. From this start the documentary is interesting, granted you have a general interest in history, but it completely lacks flare.

It is not long, though, before Häxan breaks loose from any conventions Christensen could think of. Christensen begins his odd strategy of creeping the hell out of you with live action witchcraft skits. This is where the narrative confusion and the fun begin, as he shows us what witches were thought to be like, gathering at secret hideouts, throwing corpse extremities into cauldrons, the usual. Before long the Devil (played by Christensen himself) makes an appearance, in generic yet terrifying form, complete with horns and claws. Christensen’s audacity only escalates from here. We see nuns running around insane, witches literally kissing the Devil’s butt, and more than enough scenes of devils seducing chicks, witches, and wenches. This is all damaging to Christensen’s argument against the existence of witchcraft (it’s kind of like showing a jury what the defendant looks like with a gun in his hand) but is monumentally entertaining, even when it is equally disturbing.

It’s not all fun and games, though. There are plenty segments in this documentary that are purely dark. There is monk-witch torture, monk-monk torture, and, in one of the film’s most peculiar moments, real-life director-assistant torture. Christensen introduces a medieval torture device called the thumbscrew and demonstrates it on a female assistant—who he claims begged for it. After the brief demonstration, Christensen claims to have extracted the assistant’s darkest secrets. Unfortunately, he doesn’t torture and tell.

The problem with the argument is escalated when Christensen presents scenes depicting what the supposed witches were probably really doing. With a little push from someone with a grudge, Christensen explains, full-blown witch-hunts would begin based on even the most trivial observations, such as a woman’s distressed rambling. So, what we get are scenes of what only supposedly happened juxtaposed with scenes of what probably actually was happening, with no indication of which is which. He continues this pattern for most of the rest of the documentary. We can usually assume which scenes are meant to represent the real and which the false, but by placing them on the same level, Christensen totally confuses his argument.

There is one more turn for the worse. Over half way through the documentary, Christensen changes his thesis altogether. Now he’s saying, yes, women, especially nuns, did act in suspicious ways, but it’s just that it wasn’t witchcraft; it was the same hysteria that seizes today’s insane. He then goes on to draw parallels between witches and modern-day women, like when he shows witches on brooms, followed by a woman flying a plane! By this point, the film’s argument is fully hopeless.

What really makes all of this bizarre is how the narration remains completely straight-faced throughout whole thing; Christensen, seems to be taking himself seriously. No one really knows whether he is honestly trying to prove a point or whether it’s one big tongue-in-cheek excuse to showcase startling images. There is no doubt that at some level he was purposefully trying to get a rise out of his audiences (who knew nakedness existed in the 1920s?). It’s just a question of whether Häxan is a genuinely faulty shock-documentary that swerves drastically into exploitation or an exploitation flick poorly disguised as documentary. Because the film is so well researched, I personally think that Christensen indeed started out with the intent to make an honest documentary. Perhaps as he progressed he saw his chance to turn it into something so powerfully controversial that he just could not resist. This was for the best. Häxan is much better as a horror film than it would have been as a documentary.

Aside from all of this, Häxan was a technically impressive film for its time, as Danish silent film expert Casper Tybjerg explains1. The cinematography was advanced and worked well for the film in its own right. Everything seems to exist in a nightmarish dream-haze, but the lighting of what is meant to be seen is always perfect. Sometimes that is a lot, other times it is very little. In one scene, for instance, the visual is confined to center-screen in which an apparently unbothered woman is being crawled on by what seems to be a sort of turtle-demon. The demon’s body cannot be seen, though, and the image disappears before we are completely sure of what we saw. We can always make out just enough to be disturbed. This visual confinement brings up another point. Interestingly, most of the devil scenes seem to exist without either narrative or physical context, like what is on screen is all that exists. This is troublesome for Christensen’s argument but is simultaneously successful at creating scenes that are simply and purely scary.

Häxan has numerous problems as a documentary, but as horror, it is more entertaining than ninety percent of what’s out there today. This is a total redemption for the narrative confusion. The film is probably best described by Jack Stevenson, author of Witchcraft through the Ages: The Story of Häxan, the World’s Strangest Film, and the Man Who Made It. Stevenson calls it “a mutilated masterpiece”2 (one might use the same phrase to describe the Devil). Häxan is one unforgettable movie. Just don’t expect to learn much about witches.

1 Feature commentary. Haxan: Witchcraft through the Ages. The Criterion Collection, 2001.

2 Qtd. in “Here there be Witches.” By Jason Lapeyre. Rue Morgue. Jan./Feb. 2007: 27.

Trivia:

Häxan was re-released in 1968 with narration by Beat writer William S. Burroughs. This version’s score features jazz by violinist Jean-Luc Ponty.

One male witch in Häxan probably served as the inspiration for the cover of Led Zeppelin’s album IV. The old man carrying a bundle of sticks reveals that inside those sticks he is hiding body parts of a hanged thief. The body parts were taken to be used in a potion.

Thank you for posting this.

Thank you for posting this. Very useful for my thesis. My first chapter is looking at the antecedents to modern horror found footage films and this seems to be a major one. Will have to try and find this.