Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

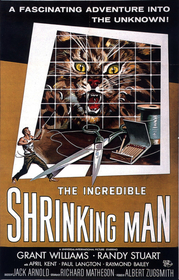

The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957)

Okay, let's face it: size does matter.

Based on Richard Matheson's novel The Shrinking Man and directed by cult sci-fi and horror guru Jack Arnold of It Came from Outer Space, Creature from the Black Lagoon, and Tarantula fame, The Incredible Shrinking Man is considered one of science fiction's best films. Its strengths, however, lurk more in the horrific implications it presents than its science fiction.

Scott Carey and his wife are enjoying a leisurely vacation on a boat off the California coast when suddenly a bizarre mist passes through them. Naturally, the happily married couple thinks little of this strange occurrence, but months later, Carey discovers he is losing weight and shrinking for no apparent reason. He visits a prominent research laboratory, and after numerous tests, learns the mist carried radioactive pesticides causing his cells to shrink. He lessens to three or four-feet, but the required adjustments in his lifestyle, although surreal, are still manageable thanks to his understanding wife. However, the shrinking doesn't stop. After befriending a circus midget, dodging the local media, and making the most of his absurd situation, Carey's size reduces to inches. He takes refuge in a dollhouse, and after surviving a cat attack, escapes to his basement to discover a wilderness of hauntingly mundane objects and critters. His struggle to survive carries on without anyone realizing he is still alive.

Carey is an innocent man living in a dangerous world governed by a wicked Fate: he's a good man and husband who finds himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. The Incredible Shrinking Man reminds us how powerful a role Chance plays in our lives, and that our most deeply held beliefs and values are rooted in unreliable perspectives that can easily be shaken. Those beliefs and values are ultimately toys that Chance and Fate play with to satisfy their whimsical needs. All this leads to a heavy dose of existential angst: no matter how small we are in the universe, we must still fight to matter, we must still fight to exist, and we must still fight to find reason in an irrational world. No matter how happy our lives may be, horror and evil are just around the corner. This struggle, which Carey triumphantly and heroically overcomes, is eloquently complimented by a poetic, fatherly voice-over electrified by Richard Matheson's poetic prose.

If The Incredible Shrinking Man is about anything, it's about the will to survive in a world we can never control. Stripped of modern conveniences, Carey reinvents himself to survive, and he does so as a caveman living in a domestic paradise that is transformed into a primordial jungle. He dons a Tarzan-like outfit, uses a pin as a spear, and travels up and down a wooden crate with thread. That this ordeal transpires in his basement, often a visual and literal reminder of our "basest" selves, is no coincidence.

The film does a fine job of revealing the mundane horrors that dwell around the corners in our lives. In an age of space travel, scientific discovery, and technical innovation, The Incredible Shrinking Man showcases the limitations of science. Carey's doctors can't effectively explain what is happening to him other than offering this general diagnosis: he has an "anti-cancer", a condition that instead of instigating the abnormal "growth" of cells prompts the "diminution" of his cells. Interestingly, his condition is the result of misguided science: radioactive pesticides.

As Elaine Tyler May argues in Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era, the suburban home and the spirit of consumerism that filled its rooms with gadgets played in the 1950s a pivotal role in promoting American values and combating Communism. She writes, "In the postwar years, investing in one's own home, along with the trappings that would presumably enhance family life, was seen as the best way to plan for the future." However, as she notes, a dark side existed behind this love affair with the consumptive American suburb that included general unhappiness, dwindling privacy, marital stress, exhaustion from working too many hours, anxiety over the need for conformity, and other deviances.1

The Incredible Shrinking Man is a metaphor of this darkness and the monstrous nature these mundane domestic objects - including pets, dollhouses, scissors, matches, and hot water heaters - could assume. The film reveals how we've become prisoners within our own homes; no place is safe: not our vacation destinations, not our environments, and certainly not our homes. No domestic insulation can protect us from unhappiness, environmental disaster, atomic bombs, Communism, or evil. We're all vulnerable.

In the postwar years, another explosive social force was the growing women's rights movement, which was accelerated by the increasingly more important role women were playing in the American workforce. More women were working and gaining for the first time a taste of financial independence. The film boasts an obvious commentary about gender too. As women - symbolized by Carey's wife - remain stable, they also gain power. As men's roles diminish, women's roles grow, and as the husband struggles to survive, the wife moves forward. Ironically, although his wife stood next to Carey on the boat, she was immune from the mist. In these uncertain times, men are more vulnerable, so the phrase "shrinking man" alludes to more than just Carey's physical dilemma.

Horror fans should ask this vital question: Who or what is the monster in this film? To which I'd reply, what isn't monstrous? Certainly, the cat and spider, drawing upon Hollywood's fascination during the 1950s with creature features, become alien-like, monolithic monsters. The mist is also a creepy monster, in the best spirit of 50s science fiction, that ultimately destroys Carey's cells. His wife and brother, and thus people and society itself, become monsters as he shrinks and they transform into giants capable of destroying Carey with one wrong misstep. Even Carey himself becomes a monster with, as he states, his "monstrous domination" over Clarice the midget. He realizes, prophetically, how size permits domination. However, perhaps the greatest monster is the vastness of the universe itself. As the film concludes, its existential leanings become apparent, and Arnold, Matheson, and Co. seem to suggest the relativity of space is the biggest "monster" we face.

Largeness and smallness are relative concepts in Carey's world, and Jack Arnold's masterful direction technically made this "size theme" one of the film's most enduring legacies. With a modest budget of $750,000 and filmed in roughly seven weeks, Arnold's film captures all that's great about independent cinema by first tapping into the hysteria over "massive" monsters and then deploying clever cinematic techniques. Arnold approached this fascination with grotesque largeness from a fresh point of view: he explored the uncontrolled shrinking of a man, not the uncontrolled growth of an insect, reptile, or another creepy beast. And through clever projection work, oversized props, split screens, and various matte shots, he delivered the visual goods to offer us a tight, economical, and ingenious film.

Many other provocative themes are only alluded to, such as the Carey's unresolved marriage, the mob mentality of the media, and the role of pesticides in California in the 1950s, but those orphaned ideas are easily forgiven. When it comes to science fiction and horror hybrids, The Incredible Shrinking Man is not only one of the decade's gems; it's also one of cinema's.

1 Tyler May, Elaine. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. Basic Books, 1988.

Zombos sent me, hence the

Zombos sent me, hence the dramatically delayed comment. Bravo on an excellent analysis of this seminal work, with good points made about science as a double-edged sword and about the film's thematic rooting in '50s concerns. In fact, given some of the similarities between the '50s and the '80s, it is perhaps surprising that the comedy remake, The Incredible Shrinking Woman, wasn't more (or some would say at all) effective. A word about the wife: in Matheson's unfilmed sequel, The Fantastic Little Girl (published in his collection Unrealized Dreams), she actually shrunk as well and caught up (down?) with Scott in his backyard paradise, joining him for some adventures before both conveniently returned to normal size, as Universal wanted Scott to do in the original. Seems that because she was down in the galley getting him a beer when they went through the mist, the effects were delayed in her case! :-) For further information, see my book Richard Matheson on Screen, which I am now frantically indexing for a tentative early-October publication.

FYI, the book is now

FYI, the book is now proofread and indexed, and should be headed to the printers. Of course, you can always pre-order it. J

http://www.mcfarlandpub.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-4216-4

Take another look at the

Take another look at the movie. Carey's wife was not standing next to him when the mist passed over the boat. She had gone down to get something and was therefore not affected by it.

I don't know man... I like

I don't know man... I like this movie, but you reviewers read way too much into this flick. Do you really think there is "darkness and the monstrous nature of mundane domestic objects", not to mention "we are prisoners within our own homes; no place is safe: not our vacation destinations, not our environments, and certainly not our homes. No domestic insulation can protect us from unhappiness, environmental disaster, atomic bombs, Communism, or evil.?" I mean come on... Yes there is plenty of psychological here, but cut the metaphoric silliness. This is a fun movie, and though I do understand that as a reviewer you want to squeeze as much fabricated transendence into your descriptions as possible, just because a movie portrays a guy shrinking doesn't mean it's automatically a metaphor about feminism.

Not all of this meaning may

Not all of this meaning may have been intended by the filmmakers, but as John Green is fond of saying, the least interesting question we can ask is, "What did the author intend here?" The most interesting question is, "What did I get out of this?" Film viewing is as essential a part of movies as filmmaking and what we bring to the film and what we take from it inform the work just as much as the work itself.

Additionally, films are not made in vacuums. They are the products of their times -- horror films often moreso than other genres, as the really successful ones tend to reflect underpinned fears of the social consciousness of their times. That's part of the thesis of Classic-Horror, really.

So, no, a guy shrinking doesn't automatically mean that there's a metaphor for feminism, but that's what Chris saw and he made a compelling argument for it. Whether you agree or not is one of the great joys of film criticism. What you bring to and take from a film reflects you as a viewer and you will have your own unique experience with the movie, which you are free to share, as you have.

"He went for a little walk! You should have seen his face!"