Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

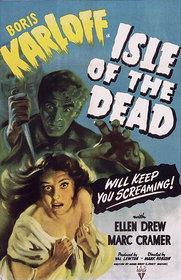

Isle of the Dead (1945)

Death casts a large shadow in all of Val Lewton's RKO horror productions, but never larger than in Isle of the Dead. Characters drop like flies as both science and superstition prove inept against the advances of the Grim Reaper in this foreboding tale set amid war, disease and encroaching madness.

Perhaps the most flawed of Lewton's chillers, this is also one of his most memorable and, in its climactic moments, the most outright frightening. The story was inspired by Lewton's fascination with Arnold Böcklin's painting of the same name, which can be seen under the opening credits and represented in the background as a Greek general (Boris Karloff) and American war correspondent (Marc Cramer) approach a small island where the general's wife is buried.

The Böcklin painting certainly suggests a perfect location for a horror film, with its looming trees and claustrophobic enclosures. (Echoes of the film's use of the painting are seen in Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island.) Lewton, who loved to use sculptures and totems symbolically, adds to that unwelcoming entrance the statue of a three-headed dog. The reporter jokingly refers to it as a watchdog, but in Greek mythology the three-headed dog is Cerberus, who guards the entrance to Hell.

Before long this island is a sort of hell indeed. Looking to investigate the destruction of his wife's tomb, the general ends up at the home of an archaeologist (Jason Robards, Sr.) whose guests include a man so ill he can't even make it up the stairs after a brief introduction. Another guest, Mrs. St. Aubyn (Katherine Emery), is also very sick. An army general confirms the worst: the plague has come to this tiny island.

Mrs. St. Aubyn's young and beautiful servant Thea (Ellen Drew) has remained suspiciously healthy as far as the archaeologist's superstitious housekeeper is concerned. She accuses the young woman of being a "vorvolaka" (something akin to a vampire), sapping the life out of all the residence's inhabitants. As things worsen, the general begins to accept this belief in his attempt to find an enemy he can defeat in the face of unstoppable death.

The significant flaws of Isle of the Dead probably resulted from a troubled production history. Lewton was at odds with executive producer Jack Gross about the horror content — Gross wanting more overt shocks and Lewton resisting — and there were extensive last-minute rewrites as they hammered out their differences.1 There is a formal quality to the dialogue in most of Lewton's films, but it is often elevated to the poetic-especially in his masterpiece, I Walked with a Zombie. Unfortunately, in Isle of the Dead it is frequently stilted, especially when delivered in wooden fashion by Robards.

All of the Lewton horror films are under 80 minutes, but this is the only one that feels rushed at times. Set during Greece's involvement in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, the movie opens with Karloff's unforgiving general demanding a subordinate commit suicide for failures in a recent battle. Cramer's newsman questions his harsh ways, but before long they are rather friendly traveling companions, as if the screenplay couldn't find any more room for a moral debate. And while the climax is among the best the Lewton unit ever staged, the denouement that follows feels like a fleeting afterthought and lacks the resonance of the curtain-closing scenes of their other films.

Filming was delayed for over four months when Karloff had to be hospitalized for a back operation. (The unavailability of other cast members upon his release would result in Karloff's second film for Lewton, The Body Snatcher, being completed before production could resume on Isle of the Dead.) A split production schedule may have added to the pressure of the tight deadlines the unit always faced and reduced the time available to smooth out the film's hurried wrinkles.

Yet the movie more than survives its evident blemishes. The screenplay by Ardel Wray, with uncredited contributions by Josef Mischel and Lewton (who always did a final revision on his films, and always — by choice — without credit) may not reach the poetic heights of I Walked with a Zombie, but it has some potent, unexpectedly moving lines. Explaining the threat of disease on the battlefield, Karloff intones a biblical reference: "The horseman on the pale horse is Pestilence. He follows the wars." Later, when the doctor (a superb Ernst Deutsch) finds he has the plague, he refuses an opiate with stoic professionalism: "I've watched so many times. I will watch this time too. Fight death all your days... then die knowing you know nothing."

Lewton's signature, of course, was atmospheric spookiness, not shocks. A couple of good jumps aside, his movies have endured because of his remarkable talent in fusing the eerie with the melancholy. But whether it was by design or pressure from Gross, Isle of the Dead offers both the unsettling and the truly startling as it reaches its climax. The fear of being buried alive gets its ultimate expression here. At first that fear is played out in indelibly understated creepiness — the camera slowly moving in on a closed casket, wrapped in the shadows of tree branches swaying in the wind. And then... a noise. It builds from there when Thea slowly walks through the same area later. Obscured by heavy darkness and aided by a strikingly modern use of flash frames, a figure appears so fleetingly you are not sure you've seen her at first. But then she makes her presence definitively known. Taken together, these scenes rank among the most bone-chilling moments from any era of horror cinema.

Lewton has always been a problematic figure for director-as-auteur purists, and Jacques Tourneur's stellar direction on the unit's first three productions (Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie and The Leopard Man) and his notable work apart from Lewton has sparked some speculation that he set a stylistic template that Lewton merely followed. If that was the case, he certainly followed it with an incredible artistic command of the directors that came after Tourneur. Isle of the Dead was directed by Mark Robson, a journeyman capable of the good (Champion, The Harder They Fall) and the truly awful (Earthquake, anybody?), but arguments about the differences in directorial style between Tourneur and Robson in their assignments for Lewton would really have to hinge on minutiae, so consistent are their films in visual style, mood and thematic content. A body of work with a recognizable personality from Cat People to Bedlam, these were Val Lewton films above all else.

Of course, he assembled as strong a team of collaborators as his meager budgets allowed, not only behind the camera but in front of it as well. Lewton essentially got stuck with Karloff when RKO executives decided his films needed more star power. Although initially reluctant to bring Universal's famed boogeyman into his fold, it proved to be a great, if short-lived, partnership. While modern viewers might have trouble accepting the clearly British Karloff as Greek, that was a common dramatic allowance of the era (and often, to my mind, preferable to actors using national accents and yet inexplicably speaking English). What Karloff gets exactly right is the desperation of a military man whose fiercely regimented ways are so thoroughly demolished by fate that he must cling to beliefs he earlier discarded with a smirk.

Ellen Drew and, in a small role, Alan Napier (Alfred from the '60s Batman series) also give nicely detailed performances. Ultimately though, the film turns on Emery's role and she is pitch-perfect as sickly, caring matron and completely unhinged later on as an avenging near-specter. Primarily a stage actress, Emery only made a handful of films. Based on this one, that was the cinema's loss.

Because its imperfections stand out more than in other Lewton productions, Isle of the Dead risks being undervalued in the producer's canon. But warts and all, there are too many unforgettable moments to not give the movie its due. As brief a run as it was (1942-1946), Lewton's RKO horror cycle remains the prime exemplar of atmospheric horror with serious thematic undercurrents. Isle of the Dead puts forth those qualities in strong fashion, and adds a nice burst of "boo!" for good measure.

1 Vieira, Mark A. Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. Harry Abrams, 2003.

This is my personal favorite

This is my personal favorite of the Lewton/RKO horror films because it captures the spirit of true Gothic horror.