Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

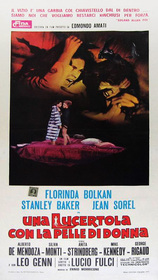

A Lizard in a Woman's Skin (1971)

After the success of Dario Argento’s brilliant giallo The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, the Italian film industry mobilized to produce a veritable bestiary of thrillers with animal-oriented titles, as if somehow that was the reason for Plumage’s box office numbers. One of the first imitators was Lucio Fulci’s A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin. Despite the similarity in titling, however, Fulci’s film is a distinct entity, with its very own illogical plot and inability to overcome its own inconsistencies.

Carol Hammond (Florinda Bolkan), the wife of a respected London lawyer, has been having vivid, erotic dreams about her bohemian neighbor Julia Durer, whom Carol knows only by reputation. Carol’s latest dream ends with her violently stabbing Julia to death. Lo and behold, Julia is soon found murdered in the exact same way. Did Carol do the deed in her sleep, or is she having psychic visions of someone else’s crime? Inspector Corvin (Stanley Baker) tries to put together an answer, but not all the pieces of this puzzle seem to fit…

Lizard is both a mystery and a thriller, so Fulci, in his capacities as director and co-writer, has two specific tasks: he must keep the viewers guessing regarding the identity of the killer and maintain a suspenseful momentum. These separate tasks should actually complement one another; give an audience a room with two people, and then the suggestion that one person in the scene might have a reason to kill the other in the immediate future, and wham, you have suspense. Fulci doesn’t care for such synergy. He treats the mystery and the thriller as completely separate entities – hell, they may as well be separate films. First, he mucks through police procedurals for a while; Inspector Corwin interviews suspects and inspects forensic evidence, all the while whistling a jaunty (read: annoying) tune. Eventually, Fulci moves the focus to Carol and her family so that they can endlessly dispute and reaffirm Carol’s sanity (and accuse each other of Julia’s murder, just for variety). When Fulci finally gets bored (and he must be bored; we certainly are), he sends in a character designed to act as the “thriller” element of the film. This character chases Carol through a location with an ungodly number of corridors and hiding places, until she runs into a room where she is confronted by some shocking animal (vivisected dogs and enraged bats – both mechanical models designed by special effects whiz Carlo Rambaldi). There are two such chase sequences in Lizard, and they must confirm Carol’s sanity, because Fulci drops the “is she crazy?” scenes and pretty much sticks to the police procedurals after the second chase is complete.

By breaking down the story into its respective parts, Fulci removes a sense of danger from Lizard. Danger is not necessary to a mystery (although it helps), but it is essential to a good thriller. How can a film thrill if its characters are only threatened in specific, cordoned sections? More importantly, how can that threat be taken seriously if it is only endangering the one character who has to survive to the end for plot reasons? Lizard does off a few other characters, but all off-screen. In one scene, a sheet is lifted to reveal the body of a rather likable member of Carol’s family. How lovely it would have been to have a harrowing sequence where we discover how she ended up under that sheet, but no. She’s alive one moment and then she is not alive the next. How disappointing that Fulci missed such a potent opportunity.

Fulci’s reticence to place his characters in danger is not caused by any squeamishness about the blood that might ensue. Even at this early point in Fulci’s horror career, he shows an affinity for jarring gore scenes. In addition to the aforementioned vivisected dogs, there is a dream sequence earlier in the film where Carol sees all of her family sitting in ornate chairs, gray-skinned and bleeding profusely from a variety of gaping wounds. These visceral shocks are extremely well-orchestrated and allude to the general direction Fulci’s career would take in later years.

Up until this point, I’ve had to avoid talking about, or indeed even thinking about, the conclusion of Lizard. If I had included the ending as part of the overall work, the previous paragraphs would have read less like critical analysis and more like an untrained chimpanzee had molested my keyboard for several minutes and then saved the file. My aggravation is this: in the last five minutes of the movie, Fulci and his fellow screenwriters tell us one of the basic truths of the film is a complete lie, told to us by an unreliable character. This is not a new technique; Alfred Hitchcock tried it somewhat unsuccessfully in Stage Fright. If Hitch couldn’t pull it off, what chance does Fulci have? The answer is, not a lot. The worst part about the ending is that it’s a conclusion we’ve almost arrived at ourselves (but probably disregarded for its inherent lameness), not because Fulci has lead us there, but because Fulci has incompetently failed to lead us elsewhere. The man doesn’t seem familiar with the elements that go into a good red herring, like motive and opportunity. Plus, our most likely suspects, two hippies who stalk Carol, are completely absolved well before the film is over. No, the only person who is taken seriously throughout the movie is the true guilty party. Having only one credible suspect is a lousy way to set-up a mystery, but it’s even lousier when a filmmaker doesn’t play fair with the facts just to keep the viewer off the scent.

A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin shows Fulci as a director not yet in his element. His later, better films would demonstrate his remarkable skill for transmuting gore and shocks into thrills and atmosphere. In a subdued thriller environment, he’s at a loss. Although Fulci merely uses Argento’s success as a springboard, he might have been better off realizing that it just wasn’t the right springboard for his talents. We might all have been better off.

This review is part of Lucio Fulci Week, the third of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

This review so completely

This review so completely blunders in misunderstanding the dynamics of 'Lizard' that it's painful to read. Fulci was doing gialli right alongside Argento (rather than 'imitating' him - see Fulci's 'Perversion Story'), so the comparison is wrongheaded (beyond the animal imagery in the title). If you can look beyond your Argento 'Plumage' bias, the film might reveal itself to you.