Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

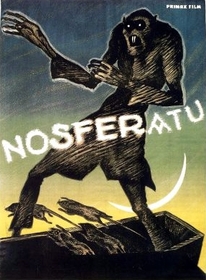

Nosferatu (1922)

An unauthorized (strongly unauthorized, as we'll see in a minute) version of Bram Stoker's novel, Dracula, Nosferatu is at least the earliest surviving cinematic appearance of that famed vampire, if not vampires in general (the first vampire appearance award probably goes to Georges Melies' short, Le Manoir du Diable, from 1896).

For whatever reasons, perhaps ignorance that such a thing needed to be done, perhaps pessimism that if sought, it would not be granted, and perhaps purely budgetary, the German production company Prana-Film failed to seek rights for Stoker's novel before lensing Nosferatu. One result of this decision is one of the aspects that make Nosferatu most interesting--it's deviation from the original story. "Dracula" becomes "Graf Orlock" (or "Orlok"), "Jonathan Harker" becomes "Waldemar Hutter," "Mina Murray" is now "Ellen Hutter," "Renfield' becomes "Makler Knock," etc.

Plotwise, aside from the fact that the names have been changed to protect the guilty, the first section of Nosferatu -- up to the point when the vampire reaches his new home -- remains little changed from Dracula. There are minor differences, but they don't impact the story much. The major differences, however, occur once the Count reaches his new abode, this time in Bremen, Germany instead of the novel's London. The material in Bremen is greatly shortened, but in a way, more pointed in subtext. Scripter Henrik Galeen's rewriting of this last section underscores a theme about the futility of love and obsession. Nosferatu is relatively quickly and easily dispatched, and on first glance, it might seem less dramatic, but the tragedy and sacrifice (there is also a parallel to the Christian messianic sacrifice) is no less effective than other vampire disposals.

More important than the plot changes, though, are the stylistic peculiarities of director Freidrich Wilhelm Murnau's vision. The most obvious difference here is the vampire's appearance. Max Schreck's Nosferatu has as much in common with rats and zombies as he does with a living human. Absent is the later depictions (essential to later plots) of a suave and debonair Eastern European upper class charmer. Nosferatu is emaciated, pale, beastly, and has long pointed claws, teeth and nose.

The term "Nosferatu" itself is a modernization of a Slavonic term, nosufuratu (sometimes spelled "nesufuratu"), which is itself a "modernization" of the Greek "nosophoros," or "plague carrier." Stoker used the word in his novel, but Galeen used it to catalyze a take that in ways is more literal and in ways more symbolic. Nosferatu is set in 1838 Bremen, the year an actual plague broke out that killed numerous citizens. In the film, Orlock is constantly accompanied by rats (which are actual plague carriers), looks like a rat himself, and symbolizes the arrival of an unknown epidemic which, when eliminated, eliminates the threat to the citizenry, as well.

A more subtle stylistic difference, though equally effective, is the production design and choice of location for the film. Just as later Draculas featured more handsome, romanticized leads, they utilized lush mountainous settings, beautiful gothic Transylvanian castles, architecturally attractive, if often unkempt Carfax Abbeys, etc. Nosferatu, in keeping with the design of the titular monster, is much more brutal than that. The way to Orlock's castle is a desolate dirt path with overgrown bushes. The castle itself is pointy, set on a pointy, abrupt hill. It's rough architecturally. It's also decrepit and foreboding in a way that suggests death like the interior of a wooden crypt. There is a shot of pretty mountains before Hutter heads to the castle, but not as the landscape where Orlock is ensconced, but rather as a contrast to what Hutter is heading into.

Orlock's new home in Bremen isn't very attractive, either. Bremen is shot in a way suggesting the expressionistic distortions of contemporaneous German silent films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Orlock's new home looks almost as decrepit as his Transylvanian one. Fritz Wagner's cinematography, unfortunately not preserved pristinely, is striking. Much of the atmospheric eerieness of the settings is due to his work, and many images, such as Orlock standing on deck of the ship taking him to Bremen, will be forever burned into your mind once you witness Nosferatu.

That Nosferatu was unauthorized is the primary reason that we have less than perfect prints remaining. Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker's widow, filed a suit against Prana which resulted in all copies that the company owned or leased being destroyed. Even later, when Universal purchased the rights to Dracula, and thus had a legal wedge for Nosferatu, copies that filtered into Great Britain and the United States were destroyed. Obviously, some rogue prints survived, and the versions we watch now are an attempt at restoring the best remaining prints.

There are many different versions of Nosferatu floating around low-budget video distribution companies. There are at least three or four different soundtracks and various extras available. My personal favorite is the Arrow Video DVD, which features a five-minute introduction by David Carradine and a soundtrack by Type O Negative. While many film fans still have a problem with watching silent films (some even protest watching black and white), Nosferatu is an essential masterpiece, not only for the horror genre, but for film as a whole.

Poor Florence Stoker was left

Poor Florence Stoker was left penniless after her husband's death and needed the money from the copyright to survive. One can feel for her and her plight when Nosferatu so closely resembles Bram Stoker's Dracula.

It also would be a shame if we lost all copies of this amazing film. I suppose that the few copies we have floating around in the public domain is the middle ground. It is a great example of Expressionist art that Galeen was noted for in his scriptwriting.

Why is it that every copy of

Why is it that every copy of this that I've seen..and I've seen three or four...has used the names from the Stoker novel with none of this Orlock/Hutter nonsense?