Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

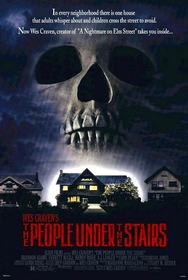

The People Under the Stairs (1991)

Three chapters define Wes Craven’s storied directorial career: the early years, the Elm Street years, and the Scream years. The Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes were pivotal because they not only shoved modern horror into its current existence, but helped shape the American New Wave that emerged during the late 60s and early 70s. The Elm Street franchise revitalized slashers and revolutionized the commercial and aesthetic aspects of horror. No villain has captivated audiences the way Freddie Kreueger has. And the Scream phenomenon resurrected a tired genre and introduced a new wave of Generation Xers to the industry. Just when many thought slashers dead, Craven screamed them back into existence.

Most curiously, though, are those niches that lurk between. Enter The People Under the Stairs. Released in 1991, People marked a weird career No-Man’s-Land for Craven: post-Elm Street but pre-Scream. However, playing with the “ghetto horror” subgenre and foreshadowing films such as Candyman, Tales from the Hood, Bones, Zombiez, and Vampiyaz, People, like so many Craven films, established the template for yet another series of fright flicks and confirmed this industry adage: where Craven goes, so goes the genre.

Meet Fool, a black teenager who lives in the ghetto with his mother and sister. Mom has cancer and needs medical attention, so Fool’s sister’s boyfriend, Leroy (played by Ving Rhames before Pulp Fiction), coaxes Fool with tough love to act by robbing their landlord’s impressive home. The landlords have a fortune stashed in their coffers, and when Leroy, Fool, and an accomplice burgle the house, the evil landlords arrive home, trap them, and an elaborate cat-and-mouse game unfolds. Fool survives, and we learn that the landlords, whose wealth has been amassed through shady real estate deals in the ghetto, are depraved and sadistic and have been kidnapping children, presumably leftovers from the families they’ve evicted, and trapping them in their basement “under the stairs”. Fool eventually escapes and returns with a plan to free the prisoners. But will he succeed? And will he erase his “foolish” reputation?

The film’s social commentary on race and child abuse is powerful and unique. The depiction of ghetto life and the desperation of Fool’s family is real, and Craven wisely posits the film’s hope and hero in Fool, who represents the next generation of black males who can correct these problems. Unlike Leroy, who serves as Fool’s antithesis, Fool reluctantly realizes that crime doesn’t bring justice. Eventually, the law and society must assist in correcting social ills such as poverty, racism, and child abuse. Ironically, Fool is the only wise man in the film. When Fool discovers the landlords’ treasures, he states, “No wonder there’s no money in the ghetto,” an astute comment that helps him understand the chaos around him. Part knight, hero, detective, and prince, Fool, played by Brandon Quintin Adams, is the film’s brightest star.

Alice, the evil landlords’ traumatized “daughter”, is also effective as the kidnapped angel who becomes the princess in Fool’s quest. Her pale, disheveled appearance symbolizes the diseases contaminating the landlords’ home and gives her a ghostly aura that represents the tortured souls living in the basement. Alice reminds us of an innocent, neglected doll, and her name conjures allusions to Alice in Wonderland and its protagonist, only this Alice is trapped in a fantasy turned nightmare.

The fairy tale allusions posted at the crossroads of urban and suburban angst make this film shine. The landlords’ home is a castle, and the brilliantly malicious Wendy Robie is the evil step mom so popular in Grimm, Disney, and Anderson fairy tales. The castle has gold, and the sadistic Everett McGill, the king of this castle, will do whatever it takes to protect his queen, kingdom, and unwilling minions. A princess is imprisoned, and that a fool outside the King’s Court is her savior is wonderfully ironic.

Alice’s room is a microcosm of the house itself and essentially, a living hell. A sign states, “Children should be seen not heard,” and later, her “mother” states, “Bad girls burn in hell,” but Alice already is in Hell just waiting for The Burn. The nooks and secret passageways behind her room’s walls serve as a metaphor for the secrets families keep and the violence and evil that in our collective unconscious lurks; sometimes, those secrets hide decades of abuse, or, much worse. The cinematography of the house and its claustrophobic rooms, dark hallways, nightmarish cellar, and “house within the house” are dusty and sickening, reminding us how deceiving reality is: surface impressions lie, and suburbia itself is an illusion masking terror.

The film abounds with mirages: monsters are not always monstrous, the innocent are not always innocent, and the weakest may be the strongest. The brother-sister duo feigns the happiness of a married couple living the American Dream, and behind their veneer of domestic bliss bleeds dysfunction, incest, and pornographic desires. The playfulness in which Craven subverts the haunted house archetype is also provocative: outside, the house appears odd but not horrifically Usher-like; travel inside, and everything is dandy; however, when you travel beneath, behind, and below its interior structures…that’s where the monsters and evil lurks.

What’s most riveting is the obvious: at times, People is down right scary, gruesome, and sadistic. Certain scenes are disproportionately graphic but work since the film isn’t bathed in gore. They serve to remind us that we’re dealing with pure evil. I recall Craven’s commentary in The American Nightmare, where he explains his ideas about “dangerous directors”. While watching McGill in certain scenes, I felt Craven’s danger: McGill prances around the house with a shotgun in an S&M leather outfit, chasing children to torture them; he draws and quarters Leroy and at one point eats his innards; and the footage of the pit where he dumps body parts… each scene is profoundly disturbing, offering images that have haunted me days after the viewing. Add the relentless Rottweiler and its pursuit of the children with the haunting appearances of the people under the stairs, and you have a frightening film offering viewers plenty to examine.

In 2008, Craven plans to remake People along with Shocker and The Last House on the Left. Each will reportedly have a budget of approximately $15 million, and Sean S. Cunningham and Craven will produce People. Rarely a fan of remakes, my interest there will be limited. The original is too good. With People, I expected another solid, scary Craven film; instead, I found something more valuable: a horrific urban tale reflecting our deepest communal sins. Stairs can be used for two basic purposes: to ascend and to descend. Somehow, Craven accomplishes both.

This review is part of Wes Craven Week, the second of four celebrations of master horror directors done for our Shocktober 2007 event.

Pretty good analysis! I was 7

Pretty good analysis! I was 7 years old when this movie came out. I remember when it came to VHS and my older sisters made me watch it, I think I just covered my eyes during most of the movie. I watched it a couple times since most often just laughing at it and how ridiculous it was. I never considered this huge subplot. Your analysis makes me think about and appreciate what Wes Craven was doing. Good work Teach! Way to practice what you preach.

Just re-watched the film.

Just re-watched the film. Noticed something that creeped me out, but isn't totally obvious, which I loved. The scene where Alice is tied in the attic and Daddy comes in, and Alice says something. Then he grabs his crotch area, and makes a, ahem, sound. Maybe it doesn't mean what I thought it meant but either way, it gave me chills.