Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

The Disused Fane: Who's Next?

Welcome to "The Disused Fane", Nathan Sturm's new column that explores the connections between death, religion, and horror movies. New entries go up the first Wednesday of every month.

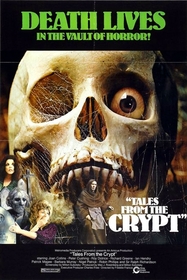

"DEATH LIVES," states the trailer for Tales from the Crypt (1972), and with its pervasive images of skulls and corpses, one is inclined to agree. Revisiting this film I am struck by how morbid and vicious it really is. It deals not just with the fear of life's end, but with the fear of what comes after life's end. From their earliest days horror films and stories have dealt with death. The imagery of decay is repulsive, and the finality of loss (Grandma isn't coming back, ever) is terrifying. We all must die. How are we to accept this? The management of this terror has been one of mankind's greatest tasks, and frequently it has fallen to one of mankind's oldest institutions: Religion.

Since the late years of the Roman Empire, Christianity has been the most prevalent religion of the West. Christianity's treatment of death combines elements of the Jewish and pagan religions. As in Judaism, death is regarded as a tragedy, the punishment inflicted on humanity for the sin of disobedience to God. As in the Greek, Nordic, and other Indo-European pagan traditions, there is belief in an afterlife, where one's stature is dependent on one's actions in life. The Christian view, expanding on the Jewish, holds that the sacrifice of Christ has redeemed humanity from its original sinfulness; the gift of eternal life is now available to any who would have it. Particularly as the Church grew in power in the Middle Ages, Westerners came to focus more on the afterlife than on the present life. "Good" actions in this life, such as faith in Christ and obedience to God's laws, would lead to eternal life in Heaven, whereas "evil" actions would lead to eternal death in Hell.

All of which leads me back to horror films. Over the centuries our religious beliefs (or lack thereof) may have changed, but our terror of death has not. The horror film has evolved over the course of a relatively secular century, in which advanced technology has allowed most of the world to see graphic evidence of wartime atrocities and read or hear daily reports on local murder cases. The knowledge that Grandma isn't coming back, the knowledge that our own thoughts and personalities will come to an end, and our bodies putrefy - this is bad enough. How are we to deal also with the realities of genocide, AIDS, and the rise of the serial killer?

In horror films, seeing other people become victims, or seeing death beaten back (as is symbolically done whenever a zombie's head is blown off), gives us a sense of relief. It isn't us, this time. Someone else has succumbed. We're still alive. But this still leaves us with the problem of all those poor victims we hear about on the news, now rotting away for no good reason that we can see.

It is at this point that an archaic Judeo-Christian concept, one often condemned for its vindictiveness, suddenly appeals to us: they had it coming.

Death is less scary and repugnant when we feel that there is a reason for it. There seemed to be no reason for the deaths of millions, many of them civilians, in the Second World War. An entire generation had to face down this horror, and then to face up to the possibility of the mass annihilation of humanity through nuclear warfare. Religiosity experience a resurgence in the postwar years as the U.S. aimed its missiles at the "godless" Communists. In this milieu William Gaines's EC Comics - publisher of Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Haunt of Fear, etc. - became popular for reviving the grisly horror story as morality play. Murderers could expect to meet with death by irony. Sometimes, death would even be meted out by the undead corpse of the victim. What is this if not divine retribution? Nature is reversed; the dead are granted a second life for their virtue and innocence, while the sinful are granted death. Lasting death, in all likelihood.

This mentality carried over into the horror films of the last half-century. Marion Crane steals money so she can elope with her divorced lover, and soon comes to a sticky end courtesy of a man pretending to be his dead mother. Bikers attempt to seize a Pennsylvania shopping mall from the people who already live there and are subsequently devoured by reanimated cadavers. Teenagers shirk their responsibilities to have sex, and are murdered by Mrs. Voorhees, whose son died due to similar neglect. Individuals with personal grievances have their own weaknesses turned against them in elaborate death-traps by a basement-dwelling, sepulchral-voiced man who is terminally ill.

However, it is in the anthology film - often inspired directly by the old EC Comics - that this cathartic, moralistic view of death is hammered home the hardest. The feature-film Tales from the Crypt involves five strangers touring the catacombs beneath a cemetery. They don't know each other, and can't remember why they're here. They stumble into a chamber dominated by a skull-like throne, where a man charmingly called the Crypt Keeper informs them (and us) that their only purpose here is to be reminded of the wages of sin. One by one each of the characters is shown to have committed some wrong, each of which then led to a nasty, ironic demise. One of them is murdered by the zombified remains of a man he drove to suicide. Another, a greedy man, leaves his wife holding his inheritance after he has a heart attack courtesy of a figure who seems to be Death himself. At the end of the film it is revealed that each of the five is already dead, and the gates of Hell open to receive them. Similar framing stories appeared in other anthology films: The Vault of Horror (1973), from the same studio, and the later Tales from the Hood (1995) being perhaps the best examples. Better-known examples of the anthology horror film also dealt rough justice to their protagonists. The first two segments in Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983) both depicted men who come to regret their nastiness and for whom death is not far off. Four of the five stories in Creepshow (1982) involve revenge served, cold of course, to the wicked, and of these, two feature the ever-popular vengeful zombie. In all of these films characters who have nothing to do with one another are lined up solely for us to discover, to our glee, that they deserved to die.

Anyone who has ever walked through a cemetery, perhaps admiring the landscaping and the quiet and the beautiful tombstones, has been jarred at some point by a realization: There are dozens of dead people all around me, decomposing a few feet beneath the ground. I'll be joining them in a few years. How comforting it must be to believe, then, that it's only the bad people who are really dead; they are the ones who are reduced to fertilizer by Nature's inexorable processes, or to cinders by the Devil and his crew. I didn't do anything wrong, so when I go, there will just be a nice tombstone and a ray of light and a beautiful place where my consciousness endures. Right?

Religion steps quickly in wherever the fear of death may be found, and in horror films, as in old ghost stories and religious parables, we can all find a cathartic release. Seeing the guilty living dragged away by the blameless dead allows us to vent our terror and anger at the thought of our own expiration. And being as it's just a movie, no one gets hurt, unlike in innumerable real-life incidents where fear-borne self-righteousness leads some people to murder. Death gets us all in the end, though - it lives, with us, every day, and perhaps ultimately we must make peace with that fact. Who's next?