Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

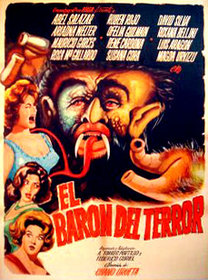

The Brainiac (1962)

The subject of repressed sexuality has long been a staple, whether as main focus or as a subtext, of genre films. It is not often, however, that it is featured prominently within the celluloid confines of a Mexican gothic horror/science fiction opus. 1962’s The Brainiac, produced by Cinematografica ABSA, ambitiously explores the idea that repressing sexual lust can lead to the lowering of morals pertaining to violence and torture. Directed by Chano Urueta and starring two of Mexico’s most popular horror veterans, Abel Salazar and Germán Robles, The Brainiac’s good ideas and intentions are buried beneath an avalanche of poor directing, ludicrous dialogue, and the lowest of budgets. Still, how bad can a film that mixes sex, sorcery, Puritanism, and high-flying comets be?

The film opens in Mexico in 1661, where a holy inquisition tribunal has gathered to pass judgment and carry out sentence on the Baron Vitelius D’Estara (Salazar), who has been convicted of witchcraft and of seducing and corrupting young maidens and married women in the local village. Despite having one character witness, Reinaldo Miranda (Rubén Rojo), appear on his behalf, the Baron is ordered to be burned at the stake out in the village square. Just before the flames consume him, a comet appears overhead in the night sky. The Baron then turns to his executioners and warns that, when the comet returns in 300 years, so will he to exact his revenge on the descendants of each member of the inquisition. Flashing forward to 1961, the comet and the Baron reappear, and a series of brutal murders occur. D’Estara now has the ability to change into a hideous monster who uses a long, forked tongue to suck out the brain of its victims.

Though the surface elements of The Brainiac are very jumbled, the underlying theme of sexual repression is fairly consistent throughout the story. The holy inquisitors shown early on are textbook examples of frigidity grown tangible. They’ve pushed back their urges to such an extent that sex, for them, has been replaced by torture. The villagers show happy, almost gleeful looks as flames consume the baron. As the action moves to 1961, the viewer is treated to slightly less inhibited but still repressed characters. There are passions just underneath the physical veneer, but an extra element or power is still needed to force them out into the open. One scene in a bar has the baron meeting a woman. She flirts with him and even kisses him a few times. When she stops and draws away a bit, the baron uses his eyes to hypnotize her. A more desire-filled series of kisses ensues before he becomes the creature and kills her. Each killing of a female victim in the movie is, in fact, preceded by them kissing the baron rather lustily, either forced or otherwise. To be fair, the male victims are also hypnotized, but the intent there is clearly to merely immobilize them before the attack. No seduction involved.

The idea of vampirism being connected to sexual repression, is strongly suggested here as well. Like Dracula and other similar vampire films, a main plot thread of The Brainiac deals with a creature who commits sexual acts or whose actions involve sexuality to an extent. D’Estara is condemned, in huge part, for having sex with lots of women and is subsequently put to death. Upon resurrection, the baron continues to seduce women before killing them and even turns into a fanged monster when doing it. Perhaps there is an innate need by the baron to bring sexuality to the fore before someone can be made to die. Even the acts of murder themselves have hints of both vampirism and sexual perversion. The lengthy, forked tongue the monster inserts at the base of the victim’s skull to extract the brain can be viewed as a phallic symbol, wickedly violating the body of an innocent and spreading corruption. It’s not unlike a certain famous vampire count we know.

It seems the “sexual repression leads to violence” thread is being offered here as a cautionary tale for viewers. We’re being told that, if a person buries lust or any emotion, they will surface in other areas at double the intensity and ugliness. The resulting repercussions could, at the very least, be equally ugly. The characters in The Brainiac pay for their frigidity by facing retribution in the form of the title creature. Put more simply, perhaps we’re being reminded that sex, mixed with common sense, is a good thing.

On a technical level, The Brainiac is right there at grade-Z turkey level. At times, director Chano Urueta shows a feel for gothic horror with a truly atmospheric and chilling opening. The burning of D’Estera scene cleverly uses muted lighting and black and white cinematography to convey mood, and is layed out at a nice, deliberate pace. In fact, the staging of the entire inquisition sequence seems to be played in a rather languid fashion, as if the players in this twisted exercise are all part of some grim ballet. All of these things combine to suggest dread and a palpable, creepy air. However Urueta, for some reason, doesn’t trust this gothic horror angle enough to stay with it. Once the action switches to modern-day Mexico, this almost physical aura of horror is replaced abruptly by the type of science fiction/horror mix that was popularized by Universal-International and other studios just a few years prior. It’s almost as if the director began work on two films simultaneously, then stitched them into one due to budget constraints. As the scene switches to 1961, the adjustments in lighting and staging are very evident. Scenes are illuminated to a much higher degree, lessening the dark mood in the process. The action is much more frenetic, especially during some of the kill scenes. Taking a cue from their 50’s brethren, the producers here decided that a rampaging creature born out of the mysteries of science or outer space was just as terrifying and imposing in broad lighting or daylight as anything that sprung from the gothic horror of an earlier era. If a viewer were to tune into The Brainiac mid-way, he or she might think the creature came from outer space and not born as a result of supernatural forces from 300 years ago.

In all fairness to Urueta, the serious tone of chills and repressed sexual urges is undermined by an unintentionally hilarious script rife with inane dialogue about 300 year curses, comets, witchcraft, astronomy and other topics. The cast, headed by genre stalwarts Salazar and Robles, nobly does the best it can. However, not much can be done when you have insipid lines like “a maniac with a lot of knowledge is a threat” or “It so happens liquor does me damage. I had a strange disease once”. The blame goes equally to scriptwriters Federico Curiel, Adolfo Lopez Portillo, and Antonio Orellana. It should be noted that the dialogue is made even more outrageous by truly awful English-language dubbing for the U.S. audience, overseen by producer K. Gordon Murray. There are no accents attempted, and the use of echo-chamber voices for the inquisitors is riotous.

The Brainiac is also undone by its own low budget. There are badly done optical effects such as the flashing light trained on D’Estera’s eyes whenever he uses his hypnotic power, and cheap visuals that are clearly the result of editing cuts. The baron’s destruction at the end is little more than a series of cuts where first a dummy and then bones from what looks like a science class skeleton are inserted. The use of obvious matte paintings, especially the ones used to depict the comet shooting through the sky during the burning at the stake scene and later at the observatory, evoke more of a groan than interest. The monster suit used, complete with grade school Halloween mask, finishes any remaining credibility the film had but is a hoot to see.

Heading a game cast is Salazar, enlivening the proceedings with his charisma and magnetism. It is difficult to tell how well an actor performs when their voice is dubbed by another actor for English-language distribution, but Salazar made a career out of using his face and hands as well as his voice. Whether offering intense gazes or commanding hand movements, Salazar displays an imposing villain like few other actors have done or could do.

The Brainiac deserves some credit for having a good idea to begin with. Using gothic horror as a platform to tell a story of fanaticism and frigid sexual mores is an intriguing, if not original, concept. It’s just a shame that it gets sandwiched inside a creative and technical mess of a film. Still if you’re into badly dubbed and low budget cinema involving sorcerers, inquisitions, comets, sexually inhibited puritans, and astronomy, The Brainiac fills the bill and then some.

This review is part of Mexico/South America Week, the first of five celebrations of international horror done for our Shocktober 2008 event.