Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

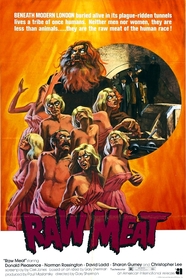

Death Line (1972)

Beginning under the neon glare of Soho’s sex district and climaxing in the pitch-black lair of a plague-ridden lunatic, Death Line is a film of constant (and contrasting) sleazy delights. American director Gary Sherman presents a 70s London brimming with violent murder, cheap sex, and a ruling class prepared to greedily feed of the destitute. Indeed, Britain’s fragmented social system seems to be his main focus. This is a country that not only stifles its lower classes, but also has the potential to create in them monsters.

After finding grotty little civil servant James Manfred OBE (James Cossins) half dead on a tube station, students Alex (Ladd) and Patricia (Gurney) fetch the police, but on returning find the body gone. The disappearance draws the attention of the eccentric Inspector Calhoun (Pleasence) because Manfred, we are told, “isn’t just a member of the public to be shut away in a file somewhere.” And as more bodies vanish, the trail leads to the last survivors of a community living beneath the city streets. But living on what?

Sherman conceived the movie whilst riding the tube late at night1 and his imagination clearly flirted with the grotesque. His underground society breeds in festering darkness and seem to be a process of a deep decay. Their faces are anaemic and boil-ridden, with thick saliva hanging from twisted mouths. They feed of anything they can catch – or anyone. It is therefore to the director’s credit that he manages to keep them sympathetic and they are as much victims of their surroundings as anybody else.

These unfortunates began as ordinary workers digging out a tube station, but when it collapsed, the company abandoned them to save money. Those in power showed no regard for their plight and the voracious greed of England's "betters," (and their value of commerce over human life) created a literal under-class of people feeding off those above.

Their environment became the labyrinths of the Underground (like an industrial version of the Parisian catacombs in The Phantom of the Opera) and the lost workers simply became part of the darkness. In a remarkable single-take sequence, Sherman’s camera creeps around their lair, passing dim gas lamps, rats chewing disembodied flesh and putrescent corpses hanging off walls. This monochrome Gothicism is set in sharp contrast to the neon exuberance of the world above.

Here we are awash with flashing signs and gaudy lights - a world of artifice and empty feeling. It is here that we first meet Manfred as he attempts to procure sex from women running out of options. He uses people for his own salacious needs and is almost vampiric in the way he feeds off societies desperate. In this way, despite their juxtaposing worlds, he is mirrored with The Man underground (Hugh Armstrong), who takes this feeding to its literal extremes.

This use of opposition and parallel is a key motif in Death Line. The Man is as a vicious killer, but he is also a caring patriarch who tends to his sick mate. The scene in which he ‘bleeds’ a dead body to feed his companion is disturbing yes, but it is also weirdly touching, as he nurses her and strokes her hair. And again, this ‘tenderness’ is set in sharp contrast to the empty romance of our lead couple above ground.

Alex and Patricia live in a world where lasting relationships are less vital and love doesn’t always last forever. There commitment is half-hearted (they don’t live together and can up and leave whenever they please). Indeed, when Patricia does walk out, Alex accepts it with a lethargic resignation, but when the Man loses his mate, his unhinged scream echoes across the underground walls – instilling it forever with his unending sorrow. But then she is all he had, all society has allowed him.

Further class dichotomy is presented in the opposition of genre veterans Donald Pleasence and Christopher Lee. Pleasence gives a career best performance as the working-class copper assigned to the case - sniffing and scratching and obsessing about tea (he even keeps a pot by his bed). Meanwhile Lee plays upper-class M.I.5 agent Stratton-Villiers M.I.5 as a smarmy authoritarian who wants to keep a lid on Manfred’s disappearance.

Stratton-Villiers mocks Calhoun for his “working class virility,” and makes it clear who’s really in control of this country. “Mind you don’t become a missing person yourself,” he warns. But though Calhoun shows a disregard for those in charge - “This is my manor, and the villains in it are mine!” he bellows in his thick East End drawl - he also displays an inbuilt acceptance of social structure. After all, when he gets “pissed” down the pub, he can’t help but show his loyalty to authority with an out-of-key rendition of God Save the Queen.

Death Line then, is a grim view of a fractured Britain. Sherman presents a world that is split, where groups have become socially adrift and in a cannibalistic frenzy attempt to feed off one another (both literally and figuratively) to survive. They are at once opposite and the same. And while the cannibalistic narrative may have paved the way for such films as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977), Death Line is more interested in ripping at the throat of a warped social structure. It takes us to the dark places.

In fact the only way to unwind afterward is with a nice hot drink. Tea, anyone?

1 Marriott, James and Kim Newman. Horror: The Definitive Guide to the Cinema of Fear. Andre Deutsch Ltd, 2008. Page 124.

I first watched this film in

I first watched this film in 1972 (when I was a precocious 14 year old ) and it has remained in my memory as one of the most disturbing films I have seen in the 40 years since.The complexities and contrasts of the social,psychological,ethical and even political perspectives all combine to challenge all the 'benchmarks' by which 'civilisation' 'society' and even 'reality' is defined.Given that this film was made pre C.G.I.,'Blue screen' etc,it was years ahead of it's time and managed to portray the authors nightmare narrative.A time fixed classic that still poses conflicts and challenges the 'black and whites' of living and dying !