Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

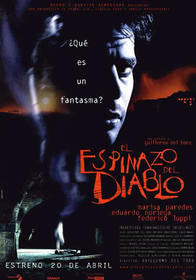

The Devil's Backbone (2001)

What is a ghost? A tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain, perhaps. Something dead which still seems to be alive. An emotion suspended in time. Like a blurred photograph. Like an insect trapped in amber.

Those words begin The Devil's Backbone (TDB), and unlike most conventional ghost stories that seek only to frighten, those words and the film itself force us to think long and hard about the definition of ghosts and their purpose in our lives. Carried by the poignancy of that luminous voice-over, those words and TDB breathed new life into the classic ghost story.

But TDB, a peculiar film from start to finish, does much more than that. One could argue the film is not scary or bloody enough to even qualify as a horror film; instead, it resonates better as a war film revealing the trauma those fighting for noble causes beyond conventional battlefields suffer. Most likely it is both, a cross-genre gem that will appeal to many.

Directed and written by Mexican-born Guillermo del Toro of Hellboy and Blade II fame, the story unfolds in 1939 Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Franco's Nationalist forces are piling up resounding defeats upon the left-wing Republicans, and the Spanish people and their landscape are being ravished. No actual war footage is ever shown, but the orphanage itself is a living testament to and a stark reminder of the horrors of war. While many children are left homeless, two soldiers bring 10-year-old Carlos to a distant orphanage in the middle of nowhere. The matriarchal Carmen and a professor named Casares manage the orphanage, and they both favor the Republican cause.

As Carlos struggles to settle in, the janitor, Jacinto, chastises Carlos after the boy disobediently explores the labyrinthine chambers of the estate's cellars. Due to a secret he must maintain, Jacinto rabidly protects this area, which contains a deep, pool-like well. Meanwhile, a boy-ghost named Santi haunts Carlos and tells him that many of the inhabitants of the orphanage will die unless the secret is revealed. Other secrets are unearthed including hidden gold, sexual intrigue, and murder. After an explosion rocks the orphanage, the boys, led by Carlos, seek to avenge the culprit behind Santi's murder and the orphanage's bad karma.

One feature that del Toro refuses to ignore is his characters. Each is skillfully developed through a holograph of emotional turmoil and is driven by primal instincts. Carlos and the other boys' quests for justice are heroic, especially since they lost their parents and have been abandoned. They are smart enough to band together and want their comrade, the boy-ghost Santi, to rest in peace. Casares is too human to disrespect. As an aging, intellectual patriarch, his attraction to Carmen is undermined by his impotence, so he re-channels his vigor into the passion he harbors for the Republican cause. Casares represents the best intentions and principles of Spain's Old World. Carmen does as well, although her physical body also haunts her: a wooden leg cripples her, and she succumbs to the lascivious and much younger Jacinto, a resident of the orphanage himself. Jacinto generates the most emotions because he is fueled by everything we despise: greed, lust, deception, lies, and violence. Without these endearing characters, the suspense and drama of TDB would disappear into the Spanish landscape.

The visual design and cinematography of the film are also exquisite. The panoramic landscapes create a paradoxical sense of isolation and despair juxtaposed against the hopefulness embodied by the clear, blue skies. Del Toro knows his horror and pays tribute to the early masters of Germany and early Hollywood with many shots full of expressionistic shadows. The chaotic basement is itself an homage to the labyrinthine chambers so prevalent in the original Phantom of the Opera. The many extravagant tapestries and furniture found in Carmen's and Casares' rooms are equally beautiful. The undetonated bomb located in the middle of the orphanage's plaza is a clever reminder of the war, missed opportunities, and misdirected violence. Many still shots could easily qualify as paintings in a museum.

The film is also inundated with political overtones about Spanish and Mexican culture and society. TDB's heart pulsates with a range of obvious generational tensions. Three generations of Spanish society are poignantly presented in allegorical form: Carmen and Casares represent the Old World of Spain, a world still defined, perhaps foolishly, by romantic idealism, tradition, and hope; Jacinto represents the next generation, one that has abandoned idealism and replaced it with selfishness, immorality, and individuality run amok; and the youngest boys, with Carlos leading the way, represent the most practical of the three generations, led by an almost hybrid philosophy of the previous two that is at times selfish but also idealistic, noble, and heroic. These four individuals serve as parallel characters; you can only understand one if you understand the other three. In a sense, they represent the four faces of Spanish history, culture, and society.

Interestingly, while Jacinto refuses to listen to anyone but his own ego and libido, Carlos and his posse of brave little soldiers not only respect Casares and Carmen, but they also listen to a dead comrade and trust the wisdom they hear. Bravely, Del Toro's rage is aimed at a target most personal to him: his own generation. His political statement is clear: for any generation to survive, it must respect, learn, and help the generation preceding and succeeding it.

The makeup artists in the film also do some provocative work. Santi, whose name is an obvious amalgam of SAINT, which points directly to the film's overtly Christian themes, is often cast in a uniquely luminous, gelatinous film. The makeup used on his face conjures images of zombies, Frankenstein, and Day of the Dead iconography.

But the most intriguing element of this film is its placement in what is rapidly becoming a new sub-genre in horror: what I call historical horror. A growing number of recent films (Dead Birds and Below immediately come to mind) have placed their horror narratives in historical contexts that add multiple layers of drama and richness to the tale. Usually, the historical setting is a major war. Dead Birds works within the American Civil War, Below within World War II, and TDB in the Spanish Civil War. This twist is innovative and delivers this new aesthetic: dealing with ghosts is scary enough; dealing with them in a submarine during World War II takes horror to a new level (as is the case in Below). TDB fits nicely into this genre because the film is as much a horror story as it is a war film depicting a tumultuous time in Spanish history.

One of the better ghost stories and war movies I've seen in awhile, TDB won't disappoint, especially if you are looking for more than blood and guts in your horror flicks.

Trivia:

Strongly inspired by del Toro's childhood memories.