Our editor-in-chief Nate Yapp is proud to have contributed to the new book Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks, edited by Aaron Christensen. Another contributors include Anthony Timpone, B.J. Colangelo, Dave Alexander, Classic-Horror.com's own Robert C. Ring and John W. Bowen. Pick up a copy today from Amazon.com!

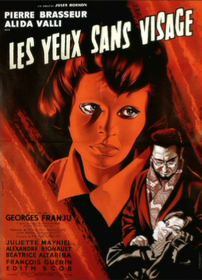

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

Georges Franju's 1959 horror classic Eyes Without a Face (aka Les yeux sans visage and The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus) opens on a woman driving a car through the French countryside. She looks nervously at the pair of headlights that are gaining on her. Her backseat passenger is cloaked in a trenchcoat and a fedora that is pulled low, obscuring his or her features. We get the feeling that there is something wrong with this person, and the driver's increasing paranoia does nothing to assuage the fear. The headlights draw nearer and finally pass the woman's car, which has stopped. The driver is relieved, but we are not -- the person in the back has slumped awkwardly. This isn't a living person after all, but a corpse that the woman will soon struggle to dump in a nearby body of water.

This sense of uneasiness unshared with the characters onscreen pervades Franju's film. The director doesn't care for the hyperbolic, nor is he interested in cheap thrills at the expense of realism. Bringing the focus back on the horror in horror films appeals to Franju, something also apparent in his 1949 nonfiction short "Blood of the Beasts" (available on the Criterion Collection Eyes DVD). Franju rejects the French term "Cinema of the Fantastic," which readily applies to most horror movies. He instead favors a stark, methodical realism, not only in the physical details of the story, but also in the characterizations themselves.

The screenplay (credited to five different writers) presents all of the necessary information for central figure Dr. Genessier upfront, well before his involvement with the corpse and the mystery woman is fully divined. Background figures comment on him -- he's brilliant, visionary, but eccentric. Incidental dialogue reveals that his daughter Christinae was disfigured in a car accident and has recently disappeared. This event has struck him badly, and we see him in a consistent state of withdrawn mourning, even before he identifies the faceless corpse from the film's opening as his offspring. He maintains tight control over his emotional wall, an ice cold mask used to keep the common people at bay. Though lecture is part of his trade, he speaks very little by way of conversation, but he does say two rather revealing things. The second most important of these is that he likes order; while this should seem obvious, it is a neat summation of his character and a sign that he is not only aware of this but feels no shame for it. The more important thing that he says, though, is that he has no hope -- a statement that makes everything that follows much more horrifying.

Eyes is about, amongst other things, control and the horrible price exacted to maintain it. Genessier is fully aware that his daughter is not dead, at least not literally speaking. She lives a half-life in his palatial home, her movements confined to its walls. Her horribly disfigured face is trapped behind a featureless mask with the only intact part of her countenance visible -- her eyes (hence the title). Her father desperately tries to restore her face, even though it means stealing the skin from the faces of others. His motives are ambiguous. He could be acting out of love, even though Christinae pleads for death and can barely handle the grisly cost of his experiments. It could be guilt, also, as it was he who caused the car accident that stole her looks in the first place. I suspect, however, that his primary reason is to bring order back to the universe by bringing beauty back to her visage. This desire leaves all of the characters in the film trapped - Christinae in the house, the woman from opening in her devotion to him, and he in his looping obsession. Indeed, cages and restraints are recurring visuals in Eyes, punctuating the concept.

Like Genessier, Franju is careful, methodical. Every action has a consequence, and every step of this journey into unsettlingly mundane horror must be examined. The camera observes squeamish events with an antiseptic detachment. The style could almost be described as documentarian (were it not for the mise-en-scene which feels too stark, too severe to be anything but deliberate stylization). The scene where Genessier is removing one victim's epidermis is filmed in its entirety; first the doctor pencils the outline of the girl's face, then cuts around the markings with a scalpel. The camera doesn't flinch as the blood seeps from the incisions in a clinical, unsensational manner. Horror fills us not because the victim is suffering -- she is sedated and blissfully unaware -- but precisely because she is not. We are alone in experiencing this simple grotesquerie, isolated from the girl who should be our screen surrogate. Our sympathies have betrayed us, and we have nowhere to place the blame; Franju's camera refuses to judge for us.

The face removal sequence (and everything leading up to it) is so detailed that it also reveals the extent of Franju's horror obsession in a curious way. The director filmed a reciprocal grafting sequence where Christinae is given a new face, but it is not included in the final film. The complete exclusion of what must be a very important scene is surprising, given the methodical nature of Eyes up to this point. Indeed, the first time we see Christinae in all of her restored beauty, it is in a scene where we also discover that the results are temporary, and the freshly transplanted skin will soon rot. It's as if Franju is deliberately avoiding anything that may be construed as uplifting; it doesn't interest him like cultivating discomfort does.

Given his druthers, I suspect Franju would have left out the fifteen minutes that follow the montage of Christinae's skin putrefication. These scenes lack the poise and depth of the rest of the film; they feel almost perfunctory, like a standard conclusion encroaching on the film, though such a banality is ultimately rejected. During these fifteen minutes, we hardly see Christinae at all. We mainly deal with a series of characters who had been inconsequential up to this point, and more or less remain that way. Franju ultimately discards the majority of these minor players for the appropriately haunting climax. While it's nice to see the movie refocused, you can't help but feel miffed at the padding that came before.

Eyes has often been called poetic, a curious adjective for a film that mires itself in the mundanites of an otherwise melodramatic plot, but it's an appropriate adjective nonetheless. The focus on de-emphasizing the more fantastic elements of a story that reaches Grand Guignol heights lends Eye a hypnotically lyrical quality. Christinae walking down the hallway in her emotionless mask becomes oddly balletic. Genessier's human motives for his inhuman deeds become epic because they're deliberately without histrionics. Franju finds beauty in the smallness of the characters, and because of this, Eyes manages to be truly horrific and beautiful at once. In fact, it's more horrific because it is beautiful.

Methodical, brutal, and haunting, Eyes Without a Face is an anomaly in the horror genre. While it's spawned its imitators -- Jess Franco in particular has photocopied the basic plot more than once -- it's never been replicated and I doubt it ever will be. It's a landmark that exists in and of itself and, as such, makes a gorgeous feast for the horror connoisseur.